And now for something completely different. Taking a brief break from current political issues and looking instead at ancient political issues. It’s time for me to write about books I read in 2024. I’ll start with all the books of ancient literature that ended up on my reading list this year.

I first read The Histories by Herodotus about 25 years ago. It was written in the 5th century BCE and is widely considered to be the first written work of history. I found it fascinating, but for some reason, I didn’t follow it up with more books by classical authors for many years. But in the last couple of years, I have become engrossed with what these early writers had to say about the worlds they inhabited. This year I’ve read a lot of Greek and Roman writing as well as two medieval Persian writers. (I don’t know what ancient Persian literature survives from before the Arab invasion of the 7th century, but there must have been some.)

Thinking about these various books written between 2500 years ago and 800 years ago for the newest work on this list, and thinking about the periods about which they wrote (all the books I read were history or based on history except for one), I kind of got curious about whether they knew each other or were aware of each other.

Here are the books I read more or less in order of when the authors were alive: The Persian Expedition by Xenophon, The Antiquities of the Jews by Flavius Josephus, Parallel Lives by Plutarch, The Histories by Tacitus, The Secret History by Procopius, Shahnameh by Abolqasem Ferdowsi, and The Conference of the Birds by Aṭṭār of Nishapur.

Xenophon was an Athenian general who got involved in Persian politics. A trivial historical fact, but learning this fact changed the way I thought of Greece and Persia in ancient history. Reading Herodotus, I got the impression that the the wars between Greece and the Achaemenid Empire (i.e. Persia) were apocalyptic events. Subsequently, I’ve heard objections that these wars were mostly significant to the Greeks. Persia had other bigger worries, but had to deal with these annoying Greeks. But what Xenophon demonstrates (and Plutarch confirms) is that Greek and Persia were two contiguous countries that had ongoing relations, both on a governmental level but also through the actions of private persons. Xenophon was such a private citizen.

Persia was ruled by a man named Artaxerxes II, who became king around 404 BCE. Artaxerxes II has a younger brother named Cyrus the Younger, who coveted the throne. Cyrus decided to engage in a revolution, and hired about 10,000 Greek mercenaries, including Xenophon. After a battle fought near Babylon, Cyrus was killed. The Greek general, Clearchus, and several other Greek officers were murdered by a Persian Satrap named Tissaphernes. The surviving Greeks vote Xenophon as their general, and Xenophon’s task was to safely march the Greeks out of Persia. The Persian Expedition is an account of that escape—we see Xenophon having to deal with disagreements among his men about their path, with hostile peoples through whose countries they had to march, and terrible weather. The ten thousand go north to the Black Sea and then west to Byzantium. It is a classic of military history and a stirring account of what it means to be a commander of an army. The action described covers about two years, 401 to 399 BCE. What is especially interesting to me is how trivial this retreat was in the scope of history. Xenophon and the ten thousand’s escape from Persia was not a turning point in either Greek or Persian history. What appealed to me most was that Xenophon described what ordinary soldiers did, as opposed to heroic supermen did (like the Spartans at Thermopylae some eighty years earlier).

Flavius Josephus (aka Yosef ben Mattityahu, 37 – 100 CE) was a Jewish military commander and historian from the first century of the common era. He has a mixed reputation. He was an aristocratic member of the priestly class in Jerusalem. In 64 CE, Josephus was sent to Rome as an ambassador, and he was highly impressed with Roman culture and military power. Jews in Jerusalem known as Zealots decided to rebel against Roman rule, and Josephus became a military commander. He was captured and enslaved. Brought before the Roman commander, Vespasian, Josephus flattered him by prophesying that he would become emperor of Rome one day. After emperor Nero’s death, and following a brief civil war, Vespasian became Emperor in 69 CE. He celebrated by granting Josephus his freedom. Josephus adopted Vespasian’s family name, Flavius, and became a Roman partisan. In the siege of Jerusalem in 70 CE, Josephus accompanied Vespasian’s son. Titus. He attempted to act as a mediator between the Romans and Jews, but was considered an apostate by the Jews and distrusted by the Romans, because the Romans were really racist against Jews. So instead, he used his royal patronage to live out his life in Rome as a historian. Josephus is mainly known for History of the Jewish War, in which he is evidently quite hostile to the Zealots. This makes him seem like a traitor to his people, and has affected his reputation ever since.

Josephus truly threw in his hand with the Romans, but he was still a Jew and wanted the Roman world to know about Jews. Hence Antiquitates Judaicae, his history of the entire Jewish people from the beginning of time to just before the war in which he participated. What is really interesting to me is that he writes in the style of a Greek history book, but its contents are largely from the Torah. The idea of history was vastly different to the iron age writers of the Torah than it was to Greek historians of the Classical age, and the Antiquities of the Jews really demonstrates how incompatible these two ways of telling history are. So much of what happened in the Bible is tribal and family-related in a way that history since Herodotus just isn’t, but Josephus tries his best to combine the two. He does mention Jesus Christ, but this is thought to perhaps be the addition of a later Christian copyist. (Remember that every single copy of every book on this list was copied by hand until Guttenberg came along.)

The neo-Babylonian empire conquered the kingdom of Judah around 598 BCE. As part of their conquest, they transported a large Jewish population to Babylon. They weren’t there long, because when Persia conquered Babylon, the Persian king Cyrus (not the Cyrus who employed Xenophon. but an earlier Cyrus) permitted the Jews to return to Judah. These Iron Age Jews were the ones to wrote down the stories of such Bronze Age myth figures like Aaron and Moses. Shortly after Cyrus set the Babylonian Jews free, the Greeks conquered Judah. Then about 150-ish BCE, the period covered in the Hebrew Bible is over. From this point, the Hasmonean dynasty begins, then is replaced by the Herodian dynasty, best-known for Herod the Great. It is super-interesting to read a Jewish writer’s impression of all these events that well-known more-or-less from the New Testament, but Josephus concerns himself with a detailed recounting of political events among the Jews. There are a lot of Simons, Johns, and Jesuses in Antiquities of the Jews. Like most detailed histories of any period, there are a blizzard of similar-sounding names which can be very confusing. (And Antiquities of the Jews is a breeze in this aspect compared to the Baburnama, which I am reading now.) But that is one of the risks of reading history.

Plutarch (circa 46 – 119 CE) was a Greek biographer who interestingly was alive at the same time as Josephus. He had Roman citizenship and was known to have traveled widely in the empire (so he could have met Josephus at some point). This book has an interesting structure. Plutarch writes a biography of an eminent Greek and pairs it with a biography of a Roman, then provides a brief chapter comparing the two. According to Brittanica, the Roman sections suffer a little because Plutarch learned his Latin later in life, but they seemed excellent to me (I was of course reading it in translation which has a tendency to smooth out the defects of the original language). While Plutarch doesn’t claim to be a historian, these biographies collectively form a history of early Rome and a lot of Greece. Greece’s history is more complex, though, given that there is no single metropole running the show. Athens, Corinth, Thebes, and Sparta didn’t rule Greece in the same way Rome ruled the Empire.

But if you cared to do the work, you could construct a history of Rome and more-or-less a history of Greece by connecting Plutarch’s biographical essays. And Plutarch does do one thing I expect historians to do—he investigates whether his sources are trustworthy and if there are two differing accounts of an event, he’ll give both. He’ll let the reader know she should be skeptical from time to time.

A 1579 translation of Parallel Lives was read by Shakespeare who used many of Plutarch’s biographies as source material for his Greek and Roman history plays. As I read Plutarch, he’d relate a familiar-seeming historical fact and I’d realize that I was familiar with it from Shakespeare. The earliest figure in the book is of Lycurgus, the legendary law giver of Sparta (he lived around 820 BCE) and the most recent biography is of Mark Antony, who died in 30 BCE.

Tacitus (56 – c. 120 CE) is the first writer in this list who wrote in Latin, and his Histories is the most straightforward telling of a historical period of any of the books here. He wrote The Histories in about 100-110 CE, and the period of time covered in them is 69 to 70 CE. In short, he was writing a history of what to him must have been fairly recent events. He is writing here of the events following the fall of the Julio-Claudian dynasty, which starts with Augustus, the first Roman Emperor, then proceeds to Tiberius, Caligula, Claudius and finally Nero. (And we can say this line began with Julius Caesar, but he never held the title “imperator” like the rest.) After Nero’s suicide in CE 68, 69 is known as the year of four emperors, and it is about these men that Tacitus wrote the Histories.

The four emperors were Galba, Otho, Vitellius and Vespasian. This is the same Vespasian who enslaved Josephus after the first Jewish War. Tacitus was alive at the same time as both Josephus and Plutarch. After Nero’s suicide, Roman legions got in the habit of promoting their own potential emperors, which is why 69 had so many of them. Tacitus gets into the gritty details of the civil war that followed as these men jockied for power in the vacuum of the Julio-Claudians. Vespasian was the ultimate winner, starting a new dynasty, which consisted of himself and his two sons, Titus and Domitian.

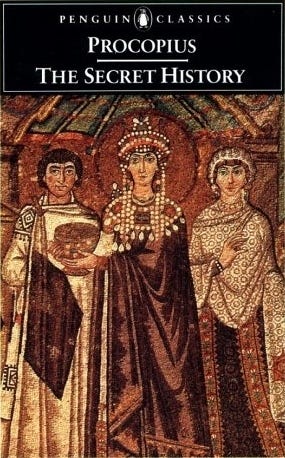

Now we return to the Greek part of the Roman empire. Procopius was alive from roughly 500 to 565 CE, shortly after the fall of the western Roman empire to barbarians. Procopius and his emperor, Justinian, were located in Constantinople, which would remain the seat of the Roman Empire until it was conquered by the Ottomans in 1453. Procopius had a job as legal advisor to Belisarius, Justinian’s extremely capable general. Procopius accompanied Belisarius on his expeditions to reconquer North Africa and Italy from the barbarians, and wrote a classic account of it, know as the History of the Wars. He also wrote a history of Justinian’s building projects, known as On Buildings. These works generally praise Justinian, as would be expected from works written by a court historian.

But towards the end of his career, Procopius wrote a scathing denunciation of Justinian and his court that he concealed. It would not to be rediscovered until the 17th century in the Vatican library. In it, Procopius writes about the flaws of Justinian, his empress Theodora, Belisarius, and his wife, Antonina. It was obvious that Procopius was embittered by the time he wrote this. Some of his complaints are laughable, like Belisarius being an incapable general (he is widely considered one of the best generals in history), or Justinian being a headless monster who haunted the palace at night. Some feel more like gossip (Belisarius was a weak man who did everything Antonina asked). Some feel like legitimate if political gripes—things that would have seemed bad if you were there, but now seem trivial in the scope of history (like unfair taxes). But some of it seems likely to be true. You don’t become Roman emperor and keep the job without being a total bastard. But admittedly, from the perspective of the twenty first century, the idea that Theodora performed live sex shows on stage prior to becoming Empress is more amusing than scandalous.

When the manuscript was discovered, the sexual history of Theodora was censored—too dangerous, I guess. But I like that stuff—partly for prurient reasons, I admit—but also because it depicts Theodora as a woman who did what she needed to to survive and thrive. And she was an exceptional empress.

Shahnameh was written between 977 and 1010 CE by an Iranian man named Abolqasem Ferdowsi (940 – 1019/1025 CE). He was apparently a descendant of the dehqân class of landowners whose families extended all the way back into the pre-Islamic days of the Sassanian empire. Ferdowsi lived in the Samanid dynasty, which claimed legitimacy from pre-Islamic Iran. The Samanids were very conscious of reclaiming their Persian identity, which had been suppressed under the various Arabic caliphates. Part of this reclamation was accomplished by commissioning patriotic works extolling early Persians. Shahnameh is a result of this Persian revival.

Before the Arab invasion, the Persian language had its own script. This fell out of use after the invasion. For about two hundred years after they were conquered by the Arabs, Persia was illiterate. But they adopted the Arabic alphabet, added a few extra letters, and Persian poetry exploded.

Even though the Samanids commissioned the work, it was finally accepted and paid for by Sultan Mahmud of Ghazni, a Turkish warlord who conquered much of the Samanid domains. It is weird that Turks would end up paying for the creation of a patriotic Persian epic, but I don’t claim to understand medieval Central Asian politics. Shahnameh was also revered among non-Persians. The Mongols, the Moghul Empire, and the Ottomans treasured this book as well.

Shahnameh became the most popular book in Persian literature from which to produce illustrated manuscripts. I have been studying this artform—Persian miniatures—for most of 2024, and am curious to discuss this art in relation to Shahnameh. Many illustrated versions versions exist, including contemporary Shahnamehs. In a way, the art history of Iran is a history of finding different ways with which to illustrate Shahnameh.

Shahnameh is usually divided into three sections. The first part of the book is the purely mythological. Like the Antiquities of the Jews, Shahnameh begins with the creation of the world by God. The first man is named Keyumars, and he becomes the first king. (The title Shahnameh translates as the “Book of Kings”.) The second section is sometimes referred to as the “heroic age” because it’s a section that deals with the adventures of Persian heroes like Rostam. It’s hard not to think of this section as mythological as well, but perhaps the best way to think of it is “legendary.” The difference between legend and myth is mostly a matter of degree. Matt Baker, when discussing who in the Bible is mythical, legendary, or historical, uses the Trojan war as an example of a legendary event. The leader of the Greek war party was a Spartan king named Menelaus. We know that Sparta was a real place that had kings. So some of what is said about Menelaus is true-ish, but the fact of his existence is still up in the air. The heroic age, taking up about two thirds of Shahnameh, feels a little like this, but it is still pretty mythological. Its heroes fight demons, dragons, witches and sorcerers. But is during the heroic age that Zoroaster preaches his new religion. This is a little poetic sandwich inserted into Shahnameh. There is a section written by a poet named Daqiqi which describes the coming of Zoroaster to the court of king Goshtap. Daqiqi was a contemporary of Ferdowsi, and he had been commissioned by the Samanid rulers to write a Shahnameh, but was murdered after only completing about a thousand lines. The job to complete the work was given to Ferdowsi, and he took what Daqiqi had written and inserted it into his own work.

Daqiqi is rumored to have a closet Zoroasterian. The Samanid dynasty was Sunni Muslim empire, and Ferdowsi was a practicing Shi-ite. But he seems to have been pretty chill with his Zoroasterian forefathers.

Then the third section is the historical age. Ferdowsi begins the historical age by telling the story of Alexander the Great. People often get names of people and places wrong when we try to identify them in foreign languages. We call it Germany, not Deutschland, for example. The names given by foreign peoples are called exonymns. For instance, Persia is just the Greek exonym for Iran, but not what the Iranians called themselves. Ferdowsi uses similar exonyms and refers to Alexander as “Sekander” and his father Phillip as “Filqus.” Filqus had married his daughter Nahid off to a Persian king named Darab, who is usually identified as the last of the legendary kings, but he could also be Darius I, the Achaemenid king who fought Greece in one of Persia’s wars. Nahib has such bad breath in their wedding bed that Darab is disgusted and has his court physicians give her and herb called “Sekander” which somehow freshens her breath (like parsley I guess). However, Darab is permanently turned off and divorces her, sending her back to Filqus. But she is secretly pregnant with Darab’s son. She gives birth to Sekander, and Filqus pretends that Sekander is his own son. In short, Ferdowsi takes Alexander, a Greek who conquered the entire Persian empire, and turns him into a secret Persian prince. Much of what Ferdowsi describes about Sekander’s life is fanciful and even supernatural, but many of the incidents he relates are things that are actually reported to have happened, such as when Alexander accompanied by a retinue of Greek philosophers met with Brahmin ascetics. (Almost all the incidents in Sekander’s life as related by Ferdowsi come from an ancient book that was popular in for centuries prior to Ferdowsi writing Shahnameh. This was The Alexander Romance, a book of uncertain origin that was read in various versions in European and Asian languages in pre-modern times).

After Alexander died in Babylon at the age of 32, civil war broke out among his generals, and a Greek man named Seleucus became king of Persia. He and his descendants ruled for a few hundred years before finally collapsing in the face of Rome to the west and Persia in the form of the Parthians to the east. The Parthians’ first king was named Aršak, from which comes the Persian name for the people—Ashkanians—and the Greek name, the Arsacids. They didn’t leave a huge record even though they ruled for several hundred years. Hence Ferdowsi only writes about them briefly, moving quickly ahead to the first Sassanian king, Ardeshir (180–242 CE). The Sassanians, unlike the Parthians, did keep records. But even though Ferdowsi had much more access to records of the Sassanian dynasty than the Parthian, he still makes mistakes. For example, after Ardeshir becomes shah, he ascends the ivory throne in Baghdad, a city that would not be founded for hundreds of years after Ardeshir died. (All those ancient capitals—Babylon, Seleucia, Ctesiphon and Baghdad—are all located a few miles from each other. As new dynasties came along, they were all eager to build themselves a new capital on this venerable spot.)

The translator, Dick Davis, points out that Persian used a lot of stock metaphors that don’t exactly make sense to modern readers of English. For example, here is a description of a woman:

The a priest discovered a beautiful young woman in the king’s private quarters: her face was as splendid as the new moon, her cheeks glowed like tulips, her eyelashes were like daggers from Kabol, and her braided hair, gathered in a knot on the top of her head, was as curled and wavy as the script the Mongols use.

Comparing her hair to “Mongol script” is interesting for two reasons. First, apparently Ferdowsi knew of the Mongols two centuries before they show up as history-makers in the 1200s. But a group closely related to the Mongols, the Uygurs did have a writing system, and Ferdowsi may have been refering to it. But also, comparing a beautiful woman’s hair to letters of a foreign language just feels poetic. Only a poet would ever use this metaphor.

The shah who followed Ardeshir was Shapur, who is famous for capturing Roman emperor Valerian in battle. I can easily look up Valerian in Wikipedia and learn that he is well-known for ordering the persecution of Christians in 257 CE. But Ferdowsi writes, “The king said to him, ‘You are entirely evil, a Christian, and an enemy of God. You say that he who has no partner, whose realm has no beginning or end, has a son.’” Ferdowsi turns this pagan Roman emperor into a Christian. Ferdowsi was writing 350 years after the fall of the last pre-Islamic dynasty in Persia. The facts he got wrong come from living in an age when libraries were produced by hand, when looking up shit for historical accuracy was a challenge (the same could be said about Josephus, Plutarch and Tacitus).

Over the past year I have been delving bit-by-bit into Persian and Central Asian history, literature, and art, and based on my admittedly shallow examination of this vast subject, Shanameh is the single most important and longest lasting piece of Persian literary art and the well-spring for all subsequent Persian art, literary and visual. There is an amazing art history of Shanameh; my intent is to look at some of those artworks over the next few months.

Some facts and figures to close this with. Shahnameh is one of the longest poems ever written by a single author (not counting Daqiqi’s section about Goshtap) and consists of 50,000 couplets.

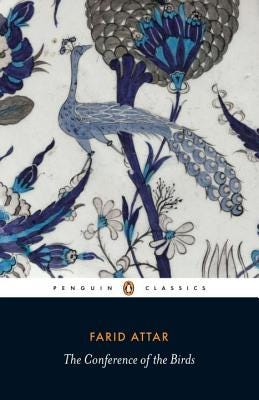

Thus far every book I’ve looked at involved history. Real things that happened to real people (or people the author thought were real) is a particular place and time. The Conference of the Birds is very different. This is a series of tales, with an over-arching story—a quest for enlightenment. The birds of the world gather to choose a king. The hoopoe, considered a very wise bird, tells them that they should seek the simurgh, a bird from Persian mythology. (A simurgh appears in Shahnameh, as well.) In order to reach the simurgh, the birds must travel through seven valleys: The Valley of the Quest, The Valley of Love, The Valley of Knowledge, The Valley of Detachment, The Valley of Unity, The Valley of Wonderment, and The Valley of Poverty and Annihilation. When the hoopoe describes the journey, some of the birds die of fright on the spot.

Just by reading the names of the seven valleys makes one think that its author, Aṭṭār of Nishapur (circa 1145 - 1221 CE), was a Buddhist or a yogi. This text is a religious mystical allegory—of Sufism. Sufism was a movement within Islam that arose in reaction to the somewhat dry and legalistic Islam promulgated by the early caliphates. They practiced a religious discipline focused on purification, spirituality, ritualism, and asceticism. It is interesting that a strain of mysticism exists in every major religion.

Aṭṭār was a pharmacist in the city of Nishapur in Northeast Iran. He was interested in sufi thought, quit his medical profession, and became a traveller, studying with sufi saints and masters all over the Islamic world.

Interspersed among the birds’ trials are a series of instructive fables. The longest of these is ‘Shaykh San‘an and the Christian Girl’, in which a pious old man from Mecca who is a religious leader in his community starts having dreams of worshipping an idol in Rūm (Anatolia). Disturbed by this, he and his followers (numbering 400) instantly take off for Rūm. There he meets a beautiful young Christian woman, who is described also as being pious. The old man falls in love instantly. There is a theological component to this story, but it is also an amusing story of a horny old goat pursuing a sexy younger woman.

At the end of the quest, thirty birds have made it the whole way. They gaze into the Simurgh and see themselves there. This is a Persian pun. Simurgh literally means 30 (Si) birds (morgh).

Aṭṭār was one of many victims of the destruction of the Khwarazmian Empire by the Mongols. After besieging Nishapur for three days, they killed every person in the city, and even the dogs and cats.

I have a morbid obsession about the authors and artists in history who were murdered by evil governments. Isaac Babel comes to mind. Or Felix Nussbaum. Let’s add Aṭṭār to the list.

This is a painting from an illustrated Conference of the Birds from the late Timurid period, around 1600 CE. The artist was named Habiballah of Sava.

[Please consider supporting this publication by becoming a patron, and you can also support it by patronizing our online store. And one more way to support this work is to buy books through The Great God Pan is Dead’s bookstore. ]

"But admittedly, from the perspective of the twenty first century, the idea that Theodora performed live sex shows on stage prior to becoming Empress is more amusing than scandalous."

From the perspective of a certain on-coming "dynasty" it just sounds familiar.

I dunno, bud. I respect your chugging through all this, but it seems to me as significant as bowling team scores from the '50s as the Turnip Reich stomps into our current lives.