In 1983, the gigantic Japanese publisher Kodansha published an important book in English, Manga! Manga! The World of Japanese Comics by Frederik L. Schodt. It was my introduction to Japanese comics. Yoshiharu Tsuge is mentioned in passing on one page. (Tsuge gets a little more space in Schodt’s followup book, Dreamland Japan: Writings on Modern Manga.) I recommend both of Schodt’s books on manga. Two years after Manga! Manga!, Tsuge’s short story, “Red Flowers,” was translated and published in Art Spiegelman’s magazine, RAW. For most American comics fans, it was the first time we’d seen the work of Yoshiharu Tsuge. The editors of RAW knew this was an important artist—the way if was printed, as a small inset booklet in RAW’s otherwise very large pages, every sound effect laboriously translated as a footnote so as not to interfere with the art. What Spiegelman, Mouly and the other editors of RAW realized was that there was something significantly different in Tsuge from any American or European comic. The editors wrote:

In spite of RAW’s internationalist bias—it assimilates work from France, Spain, Belgium, Italy, and Allentown—the only way we could integrate the Japanese work we’ve become interested in was by acknowledging its Otherness. Paris, Barcelona, Milan, and New York are all stops on the same subway line compared to Tokyo.

But since the mid-80s, Japanese culture has been adopted by Americans, partly because of kids and teenagers. They started watching Japanese animated films and reading Japanese comic in huge numbers. But for all of us who loved reading “Red Flowers” in 1985 have had to wait until 2021 to see it published in a book collection.

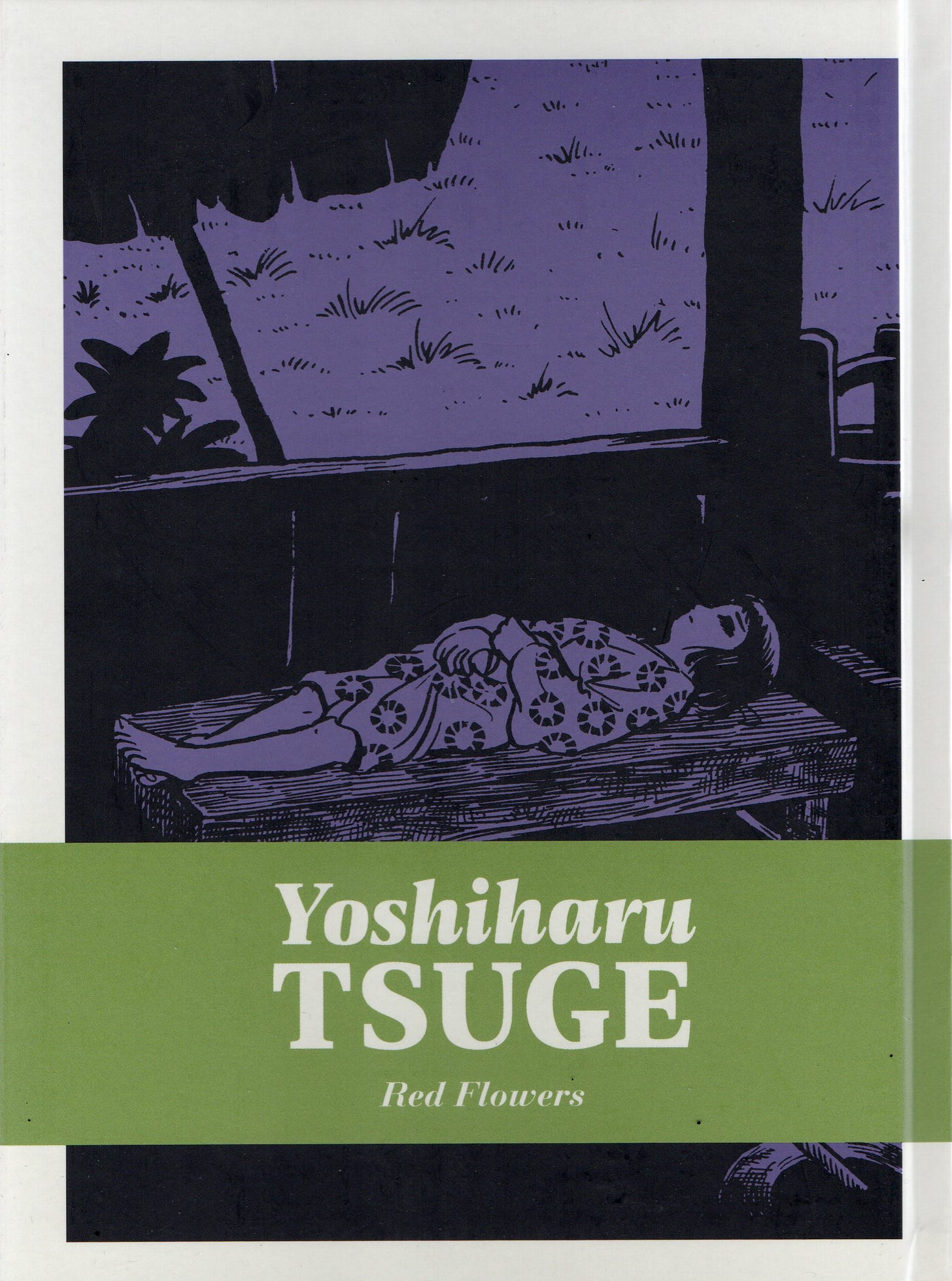

This is the second volume by Tsuge that Drawn & Quarterly has published. It’s been a long road. For a long time, it was said that Tsuge was not interested in having his work published abroad. When I first read that, I thought that maybe he was a nationalist or was anxious about how his work would be received abroad. The real reason is tragic. Tsuge is a man with mental illness who apparently was incapable of doing the work involved in making a foreign deal. I don’t know how Drawn & Quarterly and The New York Review Comics did it, but they succeeded in getting Tsuge’s work published in English in what is about the nicest format possible.

Almost two years ago, I reviewed The Man Without Talent, a startling and bleak work of autobiographical fiction that showed just how dire Tsuge’s situation had been. He and his family verged on homelessness when he was unable to produce comics, which had only provided a fairly meager living in the first place. Drawn & Quarterly’s publishing project involves publishing work from the beginning of Tsuge’s career. The first volume was The Swamp, was published in 2020. I expected a revelation but was somewhat disappointed with it. The stories were mainly rather obvious genre stories with twists. None of the stories had the poetic resonance that “Red Flowers” did, except for “Chirpy” and “The Swamp”, both from 1966. Partly this is because of the way the Japanese comics market worked at the time—when Tsuge started, he was drawing comics for the rental market—genre comics published to be rented by their reader. It was the work he could get.

But in the mid-60s, a new comics magazine called Garo appeared on the scene. Tsuge had attempted suicide, and was contacted by Garo editor Katsuichi Nagai with an offer to contribute. Tsuge had an abiding interest in Japanese literature and somehow decided to make his comics more “literary”. This volume has a long, excellent essay by Mitsuhiro Asakawa and Ryan Holmberg detailing Tsuge’s literary journey. They seem not only to have read everything that Tsuge did, but also everything he read. They write:

For contrast, look at Yoshihiro Tatsumi’s work from this period. You will notice that, while many of his stories feature characters and settings similar to Tsuge’s Garo work, Tatsumi still abides by the conventional dramatic principles of kishotenketsu, with a clear “beginning, development, twist, and ending.” Many of the stories here in Red Flowers [. . .] instead end without a clear conclusion, allowing the reader greater interpretive freedom. . . It also became a defining feature of the “Garo-esque” in manga.

Their description of what Tsuge was doing with his short stories is similar to how the prose short story evolved in the West. It may be that Tsuge seems appealing to me because in this regard, he was the most Western of the Japanese comic artists.

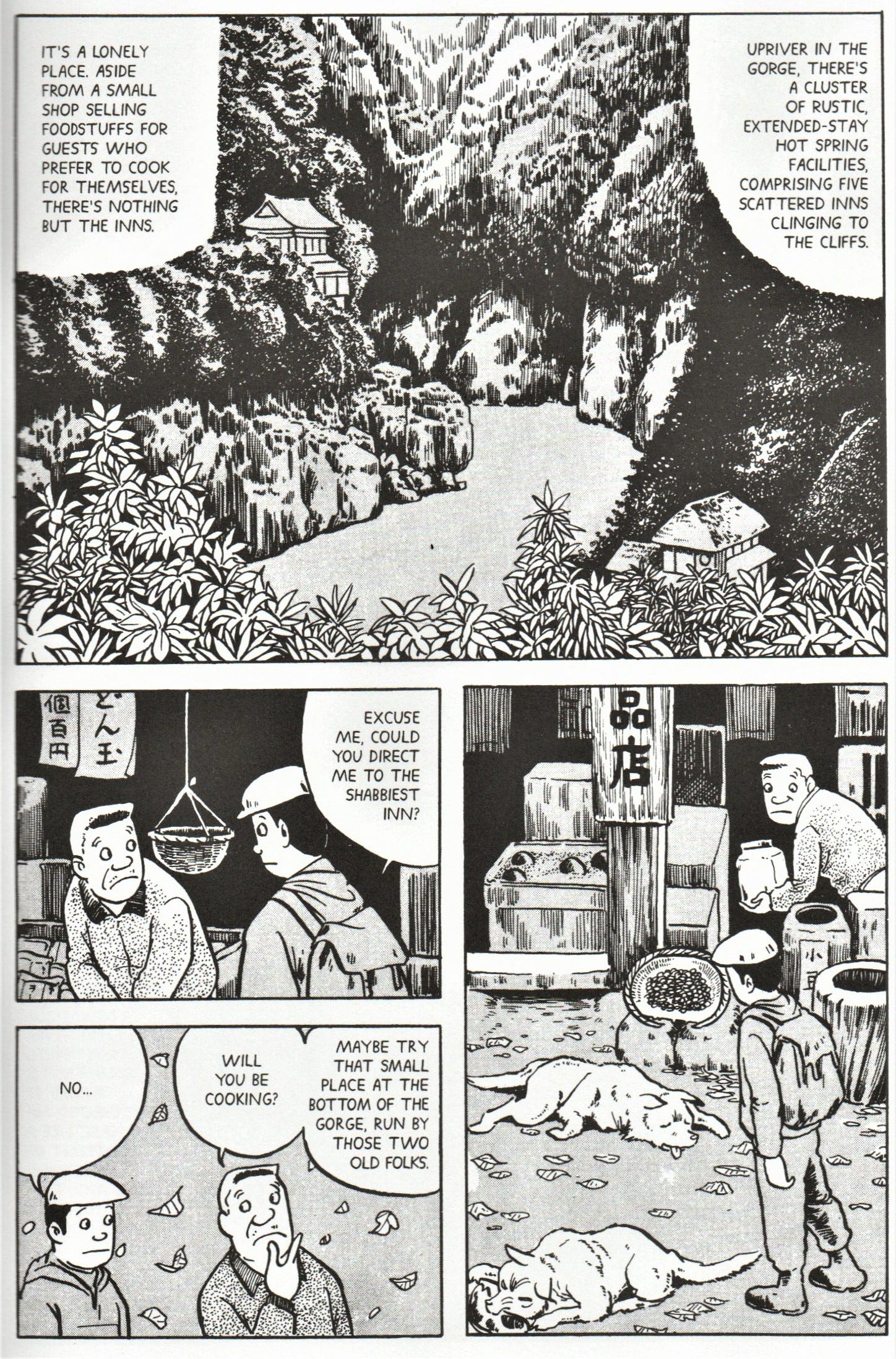

One thing that Tsuge did in the mid-60s that greatly influenced his work is that he started visiting remote rural inns, especially places with hot springs. (Some of these inns still exist, and are places of pilgrimage for Tsuge’s most devoted fans.) A lot of his stories involve the traveler from the city showing up it some picturesque rural setting to do some fishing and having a moment of mutual incomprehension with the locals. This gives Tsuge the opportunity to draw some beautiful nature into his stories. (The arrangement of the panels follows Japanese printed language—right to left, top to bottom. Keep that in mind as you read these pages.)

This love of drawing nature can be seen in this page, the first page of “The Lee Family.” The protagonist encounters an eccentric family of Koreans, the Lees, who live on his property. He has some off-putting encounters with them, and on the last page, he tells us that the Lees still live on the second floor of his rundown property.

Here he draws the isolated inns in the hot springs of “Futamata Gorge.” When the protagonist asks for the “shabbiest inn,” this could certainly be read as nostalgie de la boue, and I’m certain many of the readers of Garo looked at it that way. But I think the shabbiness appealed to Tsuge and fit his meager budget.

The story is one of unexpected encounters. The protagonist, an angler, notices there are char in the nearby hot springs. He tries to convince the innkeeper to lend him a rod, but the innkeeper points out that char are out of season. He discovers a monkey in the spring as well and is startled by it. And then a typhoon hits.

And that’s about it. Ambiguous.

Often the protagonists of Tsuge’s stories (who I always take to be Tsuge himself) has bad interactions with locals or fellow inn guests.

The page above is from “The Ondol Shack",” which is primarily about how three loudmouth guests spoil his quiet enjoyment of the hot springs. In the end, he doesn’t blame the louts, but irrationally blames the staff for giving them a room.

This page is from the story “Mister Ben of the Honyara Cave.” I liked it because Tsuge is making fun of tourists like himself who travel looking for quasi-mystical experiences, what James Joyce called an “epiphany.” But compare the Tsuge-character’s epiphany to the loutish behavior of the local fishing guide. The tourist seems like a phony to the local man.

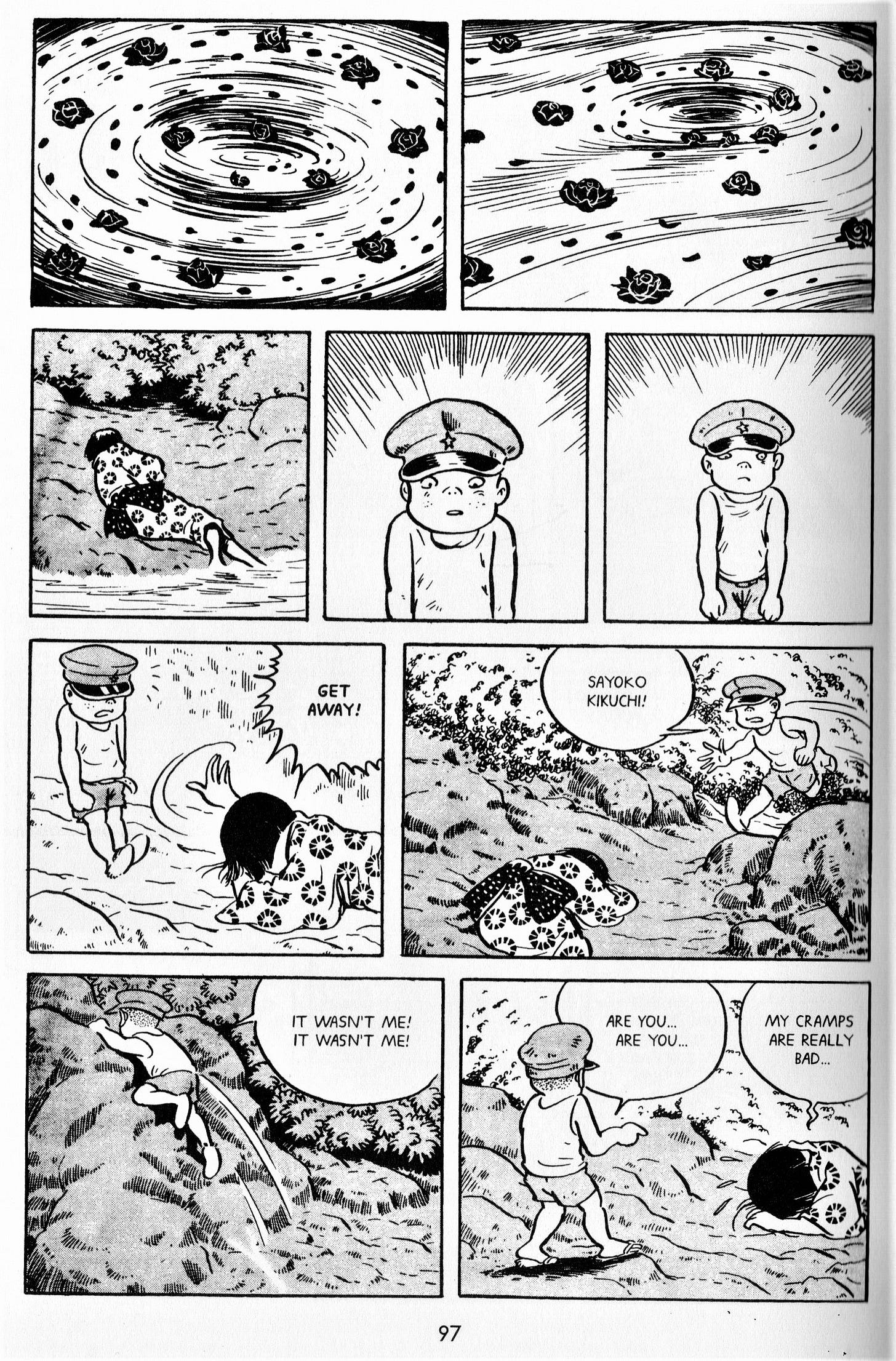

The best story is “Red Flowers.” An out-of-towner appears at a small food stand where an adolescent girl, Sayoko, is working. Instead of making her pitch to the fisherman like a normal shopkeeper, she yells it at him: “Hello sir! Stop for a snack why dontcha!” He asks her about good fishing spots, but she doesn’t know. She suggests he wait for her friend Masaji. He is a boy who wears an old military cap. He and Sayoko have a playful relationship. He’s mean to her at one moment, then nice later on.

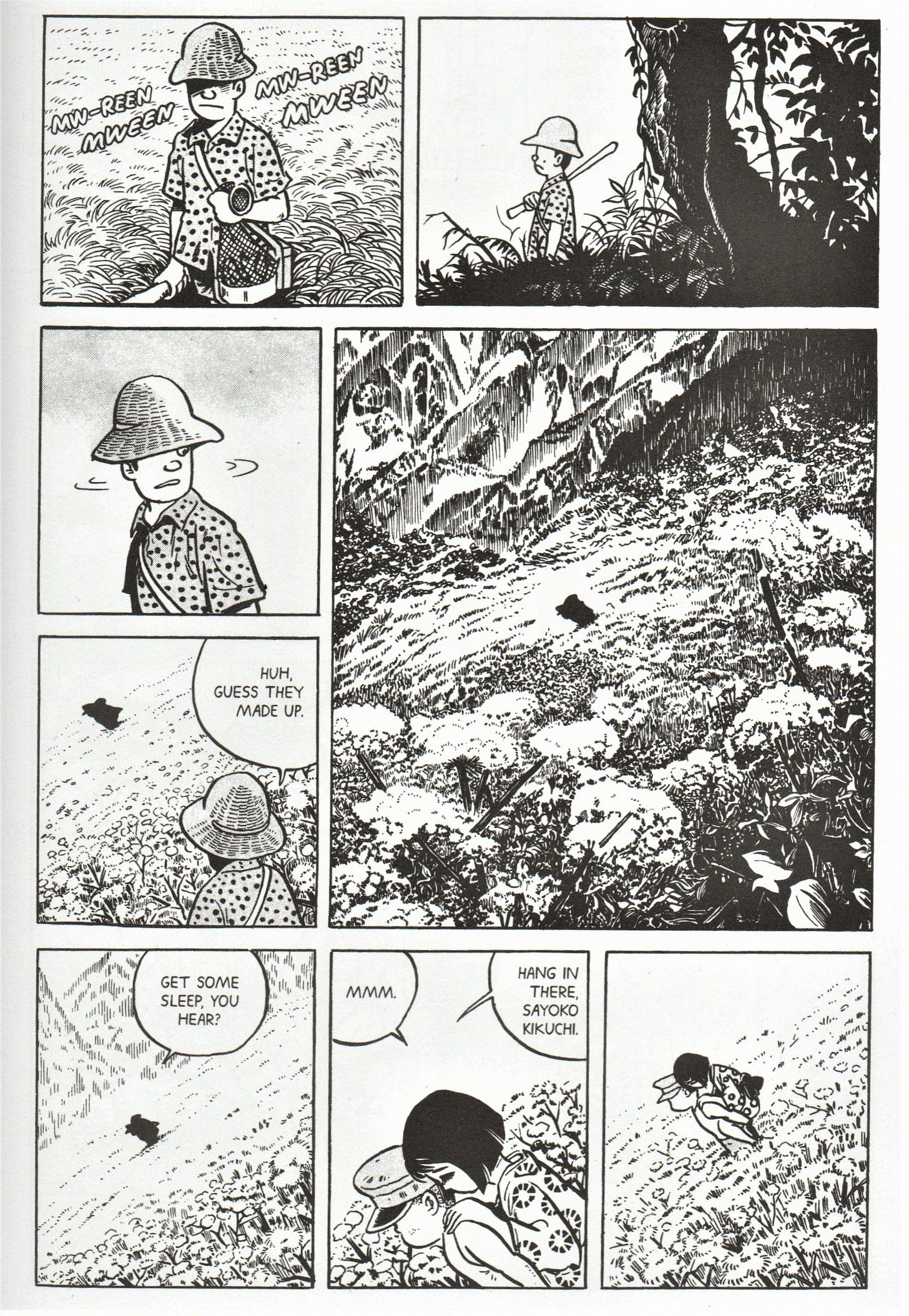

Masaji shows the fisherman a fishing hole under a shrub with red flowers. He says that char like to eat the red flowers. Masaji sees Sayoko kneeling in the water and realizes she is having her first period. Sayoko has painful cramps and is humiliated to have been caught by Masaji.

The red flowers are admittedly kind of a heavy-handed metaphor for menstruation. But the last page is what makes it a Tsuge story to me.

The fisherman sees Masaji carrying Sayoko on his back. Whatever else is going on in their lives (or the fisherman’s) is left out of the story. “Red Flowers” is a beautiful spare piece of short fiction.

This is easily my favorite comic so far of 2021. I doubt if I’ll read anything between now and the end of the year that moves me as much. This group of short stories originally published in the mid 1960s in Japan are a monumental achievement.

[Please consider supporting my work by becoming a patron, and you can also support my work by patronizing my online store. And one more way to support what I do here is to buy books through my bookstore. You can get any of the titles mentioned here from The Great God Pan is Dead bookshop.]