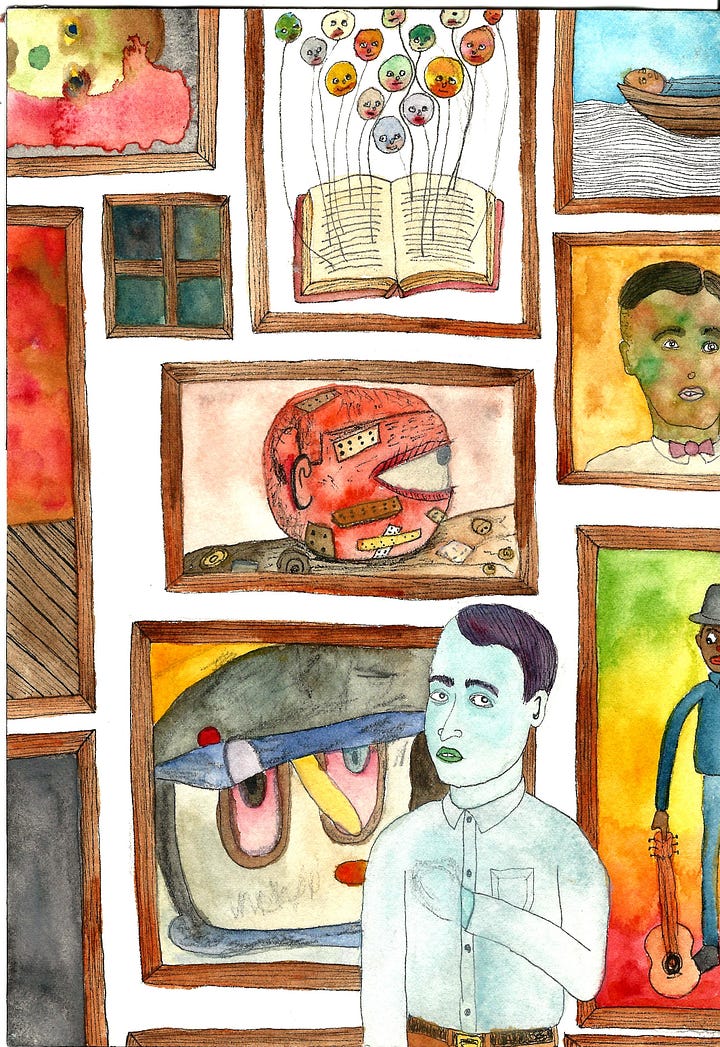

I think I became aware of Lane Hagood when he won the Hunting Prize in 2010. This was an annual prize given to regional artists by an English oil company, Hunting Plc. Hagood’s literary bent appealed to me—the painting for which he was awarded $50,000 was titled Books I Have Possessed. The painting was basically a grid of hand-painting book covers. Hagood presented himself as a bookish guy. That same year, he had an exhibit at Gallery 1724, a long-defunct art space that during the day was a hair salon. Hagood was still high on his Hunting victory when he showed up. What drew me to the work was two seemingly contradictory tendencies—Hagood the connoisseur and Hagood the crude painter of dumb things. The connoisseurship was on display in Books I Have Possessed but also in a small watercolor called The Collector, in which an art collector poses in front of a wall of paintings hung salon-style. On the dumb side was Diseased Writer. I liked them both so much that I bought them.

Hagood had a very active artistic life during the early 2010s. He had a huge exhibit at the Joanna in 2011, with an exhibit titled The Museum of Eterna. The title is yet another literary reference—it comes from an Argentine novel by Macedonio Fernández. The exhibit was full of images of Hagood’s various culture heroes, including literary figures like Georges Perec and Arthur Rimbaud. He continued the idea of art inspired by Argentine surrealist writers with an exhibit called Cronopios held in a bookstore, Kaboom. This was a two man exhibit with Seth Alverson (to whom we shall return). The two artists took the weird illustrations in Julio Cortázar’s book Around the Day in Eighty Worlds and recreated them as paintings. These small paintings were displayed in Kaboom Books, mixed in with the books on the shelves. (The title of the exhibit refers to a type of character that Cortázar included in many of his stories from the 1960s.)

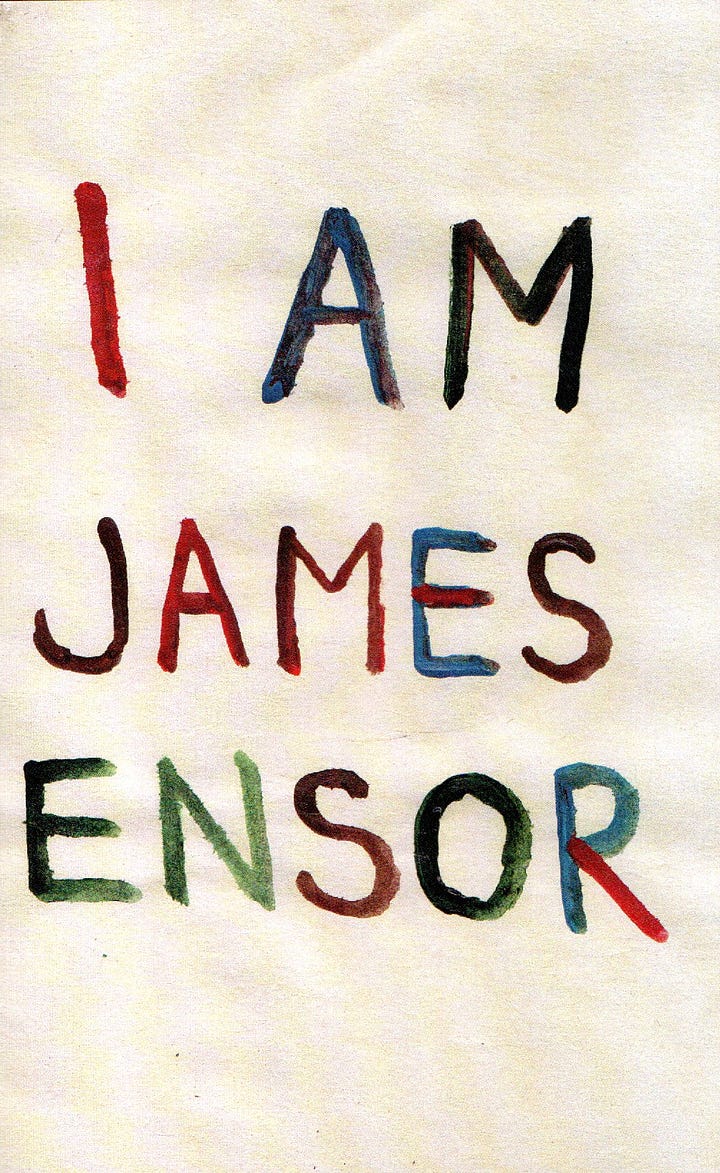

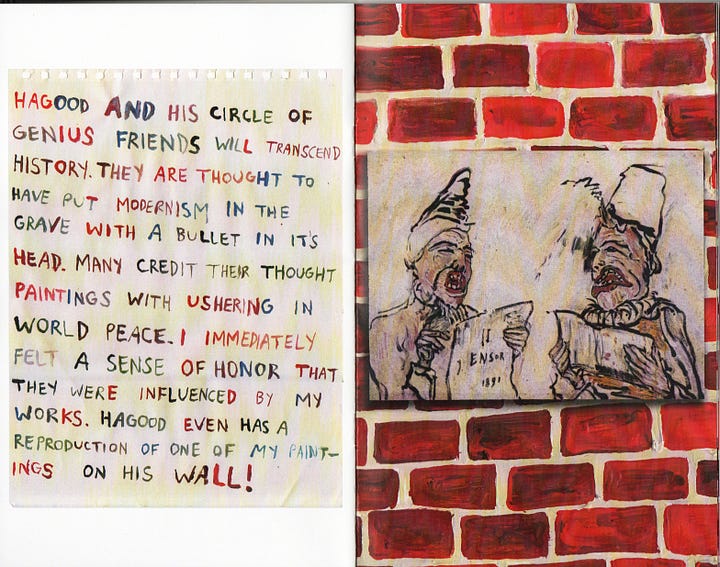

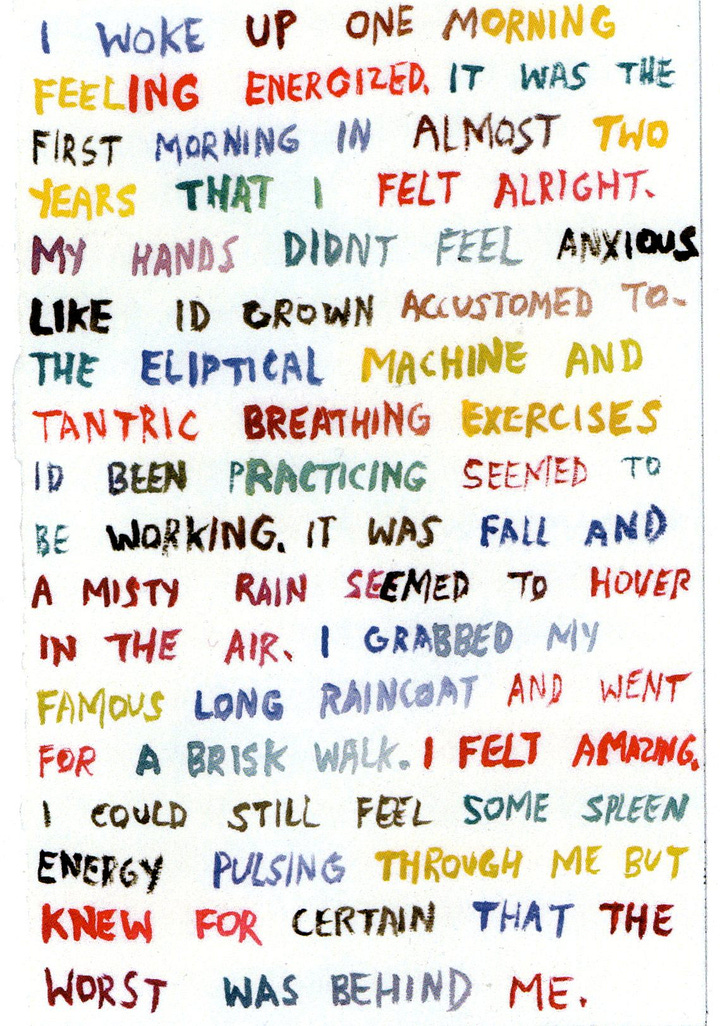

When I put on the Pan Art Fair in 2012 (held in a hotel across the street from the Texas Contemporary Art Fair), Hagood was one of the artists whose work I displayed. This was the year I first encountered Hagood the writer. He produced a zine called “I Am James Ensor” in which the ghost of Belgian painter James Ensor visits him and praises him. It is a weird literary object that primarily serves as a micro-monograph, combining photos of Hagood’s work with a weird testimonial from Ensor’s ghost. He has Ensor praise him extravagantly, so much so that it bcomees ridiculous. As a work of literature, I Am James Ensor is not memorable. But as a tribute to Ensor and a showcase for Hagood, it is excellent. One thing he did in this zine was to hand-write the text in multicolored inks. By not typesetting the text, he maintains its status as a handmade artistic object.

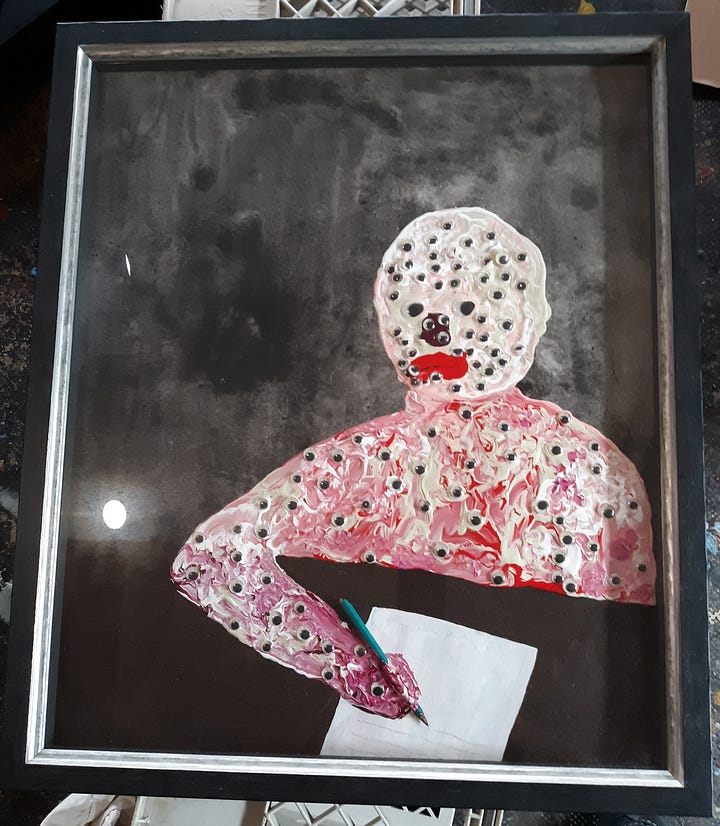

He would return to this idea in 2018, when he produced a piece of literary autofiction. Most of what is categorized as autofiction is basically autobiography written as if it were fictional. But in his 2016 book, Spleen Hands, Hagood tells a story about himself that is utterly fictional and somewhat surreal. (At least I assume it is about himself. I guess it could be about a fictional artist, written in first person.) In Spleen Hands, he is a successful artist suffering from a malady that affects “bohemian intellectual types”. Most of the book consists of color reproductions of the paintings he was doing then.

This was the last writing by Hagood that I experienced until I read Kippenberger’s Beer. I heard about a reading at Basket Books. I assumed it would be another work combining visual artwork and text like I Am James Ensor or Spleen Hands. But it wasn’t. It is a trade paperback format, roughly 5.5 x 8 inches. Larger than a mass-market paperback. (The importance of these formats was something I obsessed about in the years I worked in book publishing.) It looked so much like a standard trade paperback in its trade dress that I assumed that Hagood had found a publisher for it. After his reading, I asked him about it. The imprint that the book is published under is Cosmic Sands, which he explained was just him.

And unlike I Am James Ensor or Spleen Hands, Hagood is not a character in the book. The book is set in the New York City art world of the early 90s. The protagonist is a very Hagood-like artist, trying to make it big in the city. His name is Johnny Dabs. The things that obsess Dabs are some of the same things that obsess Hagood. For example, Dabs’ obsession with Renaissance composer Carlo Gesualdo comes from a short story by Julio Cortazar in the book We Love Glenda So Much.

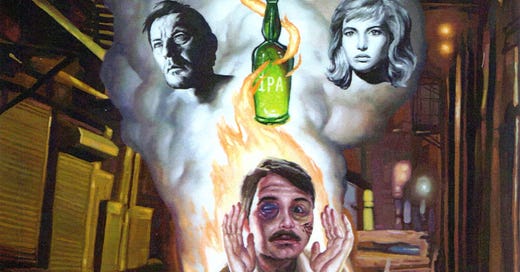

Dabs meets an artist whose work he worships at an art opening. This is Martin Kippenberger, who was an actual German artist, born in 1953 and died in 1997. (His death is an event in the novel.) The two hit it off. Kippenberger likes to hang out with Dabs and the two end up drinking some very powerful alcohol Kippenberger is carrying around—the titular IPA beer.

Kippenberger’s friendship seems to help Dabs’ career. Dabs gets an exhibit in Los Angeles due to his connection with the more famous artist. In L.A., he is given a chance to see one his favorite paintings in the flesh. James Ensor’s Christ’s Entry into Brussels. How many young writers essentially make a version of themselves into the protagonist of their first novel—quite a few, I’d guess.

Kippenberger seems to have been a fun-loving drunk in the novel. I don’t know if this is an historically accurate portrayal. German gallerist Christian Nagel (another character who exist in the real world) tells Dabs about Kippenberger. “Christian eventually just rolled his eyes. And explained that Martin was often out of money, so he bartered his work to cover his exorbitant drink tabs.” Indeed, Dabs gets a painting from Kippenberger this way.

Dabs is a regular at Max Fish, a former Lower East Side artists hangout. Hagood paints Dabs as a provincial painter from Houston who moved to New York for carer reasons. “After I graduated, I began getting involved with the local art scene, befriending the artists whose work I admired, meeting collectors, and doing my best to get to know the curators of all the local museums. I had a solo show of my paintings at a friend’s house gallery and sold the show out. A few months later, I won a very large cash prize for a drawing I’d made. Feeling like I had conquered the provincial scene, I decided to try my luck in New York City.” Dab’s career is essentially the same as Hagood’s, except moved back in time about 15 to 20 years.

Dabs both aspires to being a successful artist while maintaining a sneering contempt for the milieu. He describes an exhibition opening party like so: “I scanned the room for familiar faces, and saw a few movie stars, some young model waifs, a bunch of loser artists like myself; fancy finance bros; collector types; conservative-looking curators; art consultants; a bunch of old hipster heads; and plenty of young ones looking to take their rightful places in this snobbish milieu. “

He is dismissive of his art schooled peers. He describes them as having “Master’s degrees from Yale, CalArts, RISD, Columbia, Hunter, or any other place where you could pay six figures to get connections.” He describes their art as reactionary imitations of neoexpressionism that was popular a decade earlier.

Through Kippenberger, Dabs meets Jacques Debiurre, a sinister figure who supplies Kippeberger with his IPA. Debiurre reminds Dabs of the renaissance composer Carlo Gesualdo. Gesualdo-s is known for his madrigals and sacred music. Gesualdo is also known as a murderer—he killed his wife and her lover when he discovered them in bed together. Hagood uses this biographical fact to declare Gesualdo’s music disturbing. (That is not my impression of Gesualdo’s music, but I will leave that for my readers to judge.)

“I had known Jacques was rotten to the core the first time I saw him in L.A. I mean, he looked like the musical genius and murderer Gesualdo, and that couldn’t be a good thing. He was a slimy piece of shit.”

Debiurre makes Dabs a deal. If he will store cases of the IPA in his loft, Debiurre will pay him $20,000. Dabs is too poor to turn this down. The floor space of his loft is packed with crates of beer. But it’s not just beer—we later learn that it contains beer, laudanum (a tincture of opium), and liquid LSD. Dabs (and presumably Kippenberger) are addicted to the stuff. Weirdly enough, Dabs agrees to store it—twenty grand is hard to turn down.

But it is clearly some shady biznis. And things just get shadier. Dabs describes the next events succinctly, “When I got back to my building, I couldn’t believe it’d been less than twenty-four hours since I’d first left for Elena’s pop-up show in the Village. I’d gotten drunk, gotten laid, gotten chased, gotten kidnapped, nearly gotten killed, and gotten interrogated by the homicide division of the NYPD, all in the span of twenty-four hours I’d accomplished a lot. Oh, and I’d found my first dead body. Couldn’t forget that accomplishment.” Debiurre and two of his goons beat Dabs up, mainly to remind him to keep silent abut the IPA. At one point, all the IPA has disappeared from Dabs’ loft. Dabs is unnerved that someone had broken into his loft to do this, but it was Debiurre’s men. Later the beer is just as mysteriously returned.

This is where the free section ends. Unless you want to read major spoilers, don’t read any further.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Great God Pan Is Dead to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.