When I was living in Brazil, I sent a blind submission to my favorite magazine, The Comics Journal. This was 1988. They published the review and soon after offered me a job. I was hired to be the reporter for The Comics Journal, a job for which I was profoundly unqualified. Amazingly, I wasn’t fired. Instead, I became an editor for Fantagraphics Books, the parent company of The Comics Journal, for the next four years. I wrote frequently for The Comics Journal, just not as a news reporter. My relationship with the Journal in the early 90s was editorial gofer—transcribing interviews, writing captions and cutlines, proofreading, operating our typesetting machine (this was in the days just before desktop publishing technology—I had an IBM Selectric typewriter on my desk, not a computer). As I look back on that era, I can see that I joined right when Fantagraphics decided to go big on publishing art comics. It was the perfect place for an artsy young comics-loving man to work.

One of my jobs at Fantagraphics was to look at unsolicited comics submissions (occasionally I got lucky—for instance, when cartoons by JIS and a story by Dave Cooper crossed my desk. But rarely.) A lot of what was submitted to Fantagraphics was in the form of minicomics, a kind of ’zine done in comics form. Minicomics were a whole thing back then, and I proposed a to write a column about them, because we were receiving so many interesting minicomics that we did not have the capacity to publish. I thought a column about new minicomics would make examples of this mostly invisible genre at least known to readers, and they could be mail-ordered (the only way to get them). After I left Fantagraphics, I continued this column for several years.

I therefore got to know some of the editors of the Journal after I was no longer staffer. Because I wrote a semi-regular column and occasionally wrote other pieces for them, and because I was a loud presence on some of the early message boards of the internet age, I was a somewhat respected comics “scholar”. There were hardly any actual comics scholars—people who studied comics in an academic setting. At the time I worked for the Journal (late 80s) I knew of three, but a whole generation of them has entered academia since then.

Up until about that moment in the art history of comics, comics were considered a stupid form of entertainment for slow children. Studying comics as works of art made no sense. The Comics Journal disagreed. We (the staff, the contributors, the publishers Kim Thompson and Gary Groth) were eager for comics to have a similar respect as other media did—literature, fine art, cinema. As an art form, comics were considered on the level of professional wrestling.

We looked at how other art forms existed in American society with unabashed envy. The Comics Journal longed for the cultural cache of magazines like The New York Review of Books or Artforum. They were serious magazines, produced by a cadre of serious critics and scholars, read by sophisticated lovers of art and literature. Anytime a work of comics art was taken seriously by cultural gatekeepers (like The New York Times), we were thrilled and felt like we were helping to make this art form something those gatekeepers could take seriously.

In 1999, the then editor of The Comics Journal, Tom Spurgeon had an idea for a magazine feature that would help to create a canon of comics. Ideally it would be a somewhat authoritative list of the comics you should know something about. The British Film Institute, via their publication, Sight and Sound, conducts two polls on the best films of all time (one a poll of critics and academics, the other a poll of directors and film-makers). I think that virtually every American who has seen Tokyo Story watched it because of the Sight and Sound critics poll. I don’t know if it was specifically this poll that inspired Spurgeon, but it surely must have been on his mind. Certainly when they sent word to their columnists, I think most of us instantly saw it as a canon-building idea like the Sight and Sound polls.

I saw it as a way to tell our readers the comics they needed to be aware of in order to be educated readers. Having a mutually agreed to set of classics seems like a minimal first step for an art form to be recognized as “art.” I think the average Comics Journal reader would agree that Krazy Kat and Maus were “classics”, but having a list that you can refer to is handy. Understanding why Krazy Kat is great takes time and effort, but a list is easy. I’ve never seen Close-up by Abbas Kiarostami, for example, but I assume it is artistically significant by virtue of its position at #9 on the 2022 Sight and Sound critics poll. I hoped that the Journal’s poll would have similar authority.

Not every columnist participated (Robert Fiore didn’t like the idea of it), and one of the participants, Eric Reynolds, was excluded due to a conflict of interest concern, since he was Fantagraphics’ marketing guy, and Fantagraphics books were surely likely to be well-represented on the list.

I wasn’t present for tabulation, but evidently there was a lot of discussion about how to split up certain author’s works. For example, Jaime Hernandez has multiple stories on the list, but his stories are, in a sense, all part of one long story that he has been publishing in Love and Rockets since the early 80s. I can see why these two stories were listed separately—they both are self-contained, even if some of the characters overlap. But this criterion could have been applied to Dirty Plotte by Julie Doucet, the autobiographical stories of Spain Rodriguez, or the Alec stories by Eddie Campbell. And the reasoning for their decisions was kind of opaque. Aggrieved readers concluded that it was the Journal pimping for Fantagraphics products.

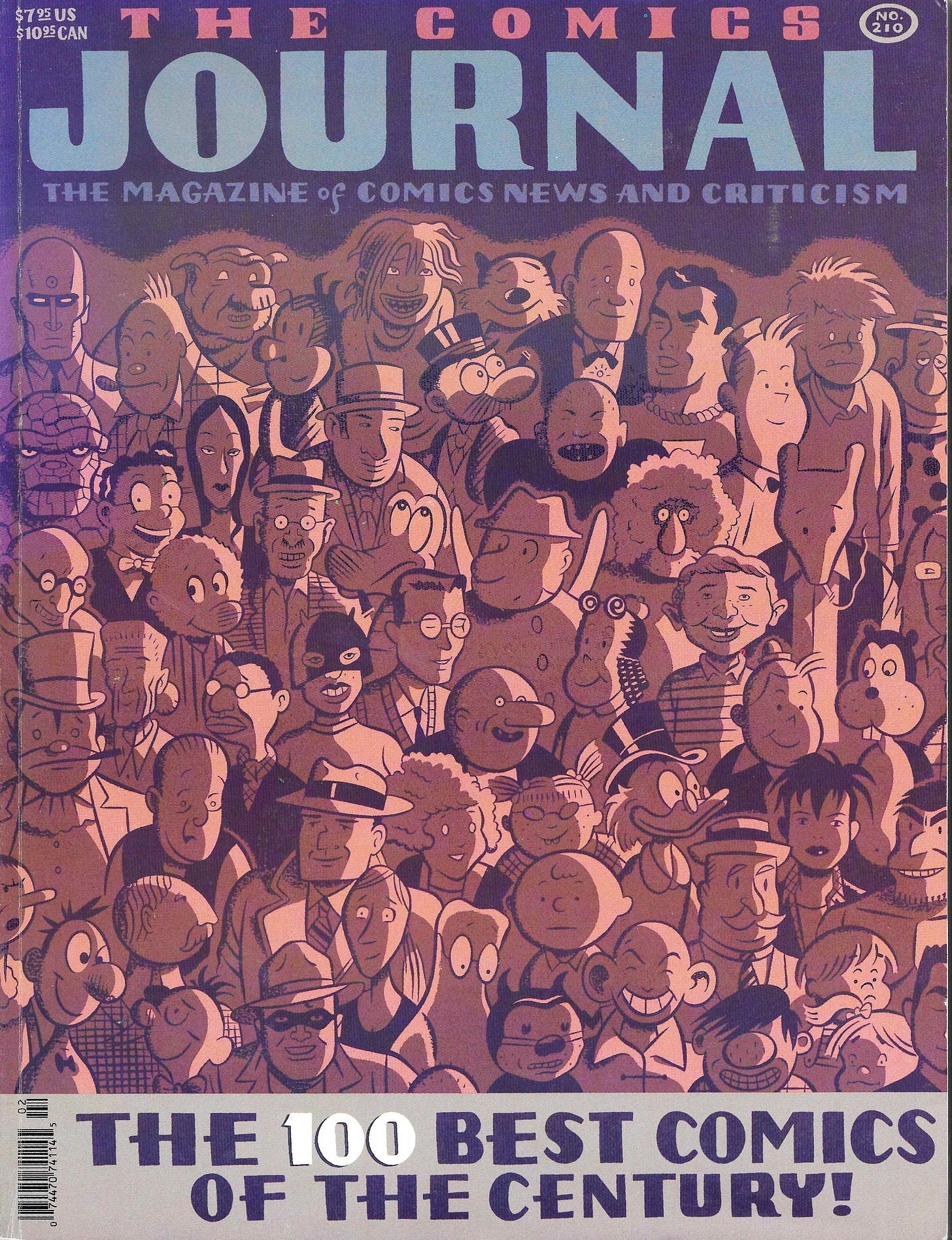

I was proud of the issue when it came out. I loved the cover by Seth, which was like a group photograph of characters from the top 100 comics on the list, drawn in his trademark Peter Arno-style pastiche. Once the list was finalized, Spurgeon assigned each of us columnists to write about some of them—and frankly, this was the part of my task that I worked hardest on. I don’t remember spending much time compiling my list at all.

I wrote about Spain Rodriguez, Stuck Rubber Baby by Howard Cruse, Eddie Campbell’s autofiction, “The Death of Speedy Ortiz” by Jaime Hernandez, and “Sick, Sick, Sick” by Jules Feiffer. Reading over my entries reinforces some of the criticism that the list received later—in writing about “The Death of Speedy Ortiz”, I can’t help but include it as part of a single narrative that Hernandez was creating in Love and Rockets, begging the question of why any of his stories should be listed twice here.

I was proud of what we had done, and intrigued to follow the controversy that followed, but “The 100 Best Comics of the Century” did not seem to acquire the cultural cache of the Sight and Sound polls, nor has The Comics Journal made a point of updating the list every ten years. We produced the list once, sold a few copies of the magazine, and life went on as it had before.

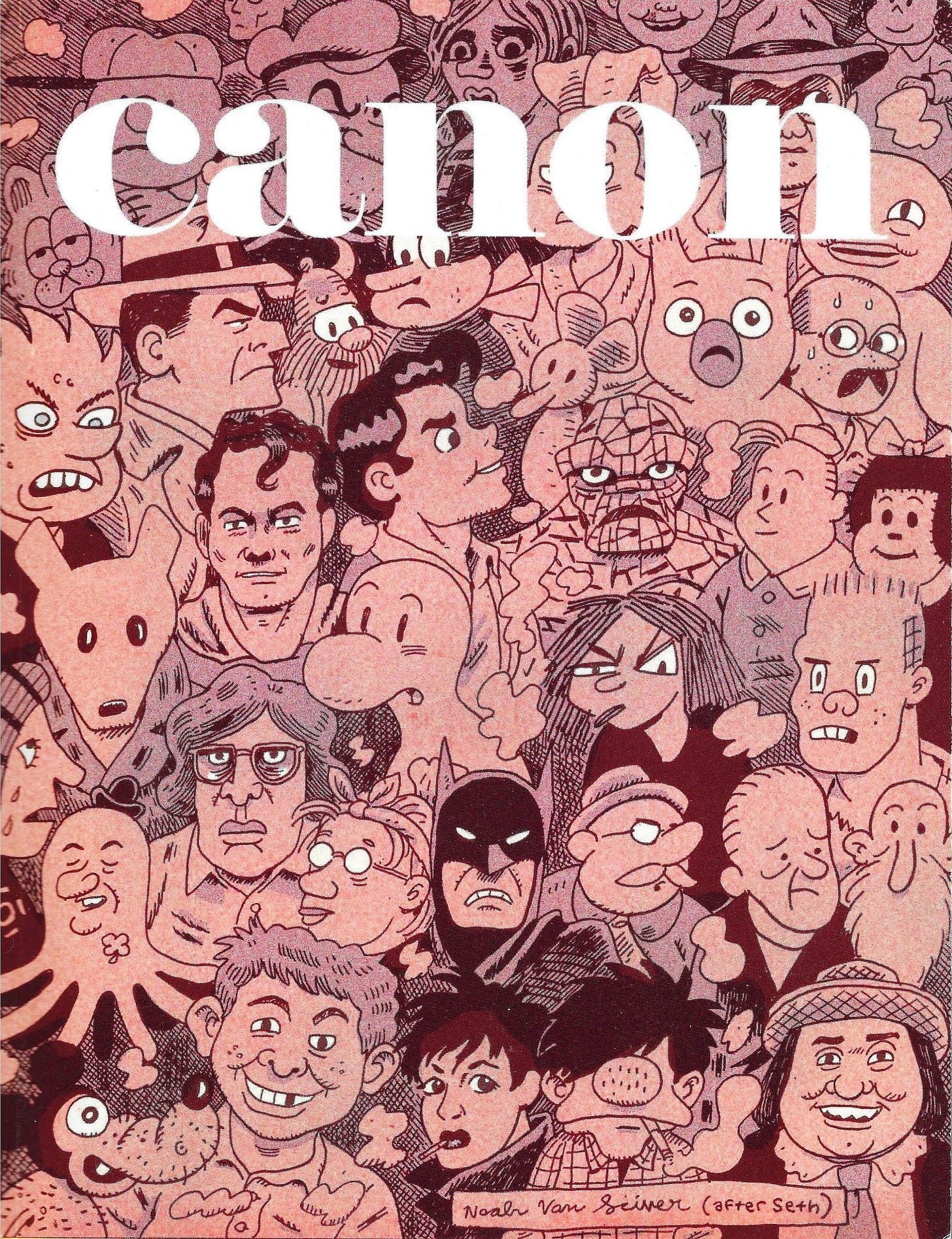

But I’ve changed my mind—I think “The 100 Best Comics of the Century” did have an observable effect on how people view the art of comics. I changed my mind because of Canon Annual 2024, a 124-page ’zine (although it feels wrong to call anything this massive a mere “’zine”). Canon is a ’zine about the making of “The 100 Best Comics of the Century” and its aftermath.

The cover is an homage to Seth’s Comics Journal cover by Noah Van Sciver, a prolific cartoonist who occupies a similar space in today’s comics world that Seth occupied in 1999. Although he adopts the same “group photo” layout that Seth employed, many of the characters he places on his cover didn’t yet exist when the original Top 100 list was compiled—a little anachronism that I like. It reminds us that time doesn’t stop, and new, exciting works of comic art keep getting made. Personally, I can’t disagree with Van Sciver’s inclusion of Jimmy Corrigan, the Chris Ware character, of Jeffrey Dahmer from the harrowing My Friend Dahmer by Derf Backderf. If I were making a new “Top 100” list, I’d include both.

Basically. Canon is a ’zine produced by two comics ultra-fans, Colin Blanchette and Alex Eklund, and in this issue, they construct a history of the assembly of “The 100 Best Comics of the Century” and its aftermath in the world, both critiquing the choices and updating us on what comics from the list are in print. They conducted short interviews with most of the contributors (including me), then sat down with each other and went through the list one by one, giving their reaction to the entry under discussion, with an emphasis on each choice’s place in the art history of comics. This discussion is the longest section. It reminded me of the kinds of discussions we had in the Journal offices all the time. They follow up on each of the cartoonists listed on the list (some of whom died in the intervening 25 years since the List was published), and on the availability of each comic. There is a little discussion of notable omissions to the list and of the vigorous online response to the list when it appeared in 1999. It concludes with an essay, “The World We Dreamed Of: The Comics Journal’s Role in the Evolution of Comics,” written (I think) by Blanchette.

In this essay, he points out how utterly quixotic The Comics Journal’s mission was when it was founded in the mid-70s. “The idea that comics could be great art for a literate, adult readership was a hypothesis without a lot of available evidence to back it up in 1976.” So what effect has the “The 100 Best Comics of the Century” had on the place of comics in our culture? Blanchette points out that “in the years following the Top 100 list’s appearance in The Comics Journal #210, the graphic novel achieved dominance over the “floppy” comic, more adult readers have found their way to comics through bookstores, and comics began to be taken seriously by those outside the parochial tribes that populated the comics industry.”

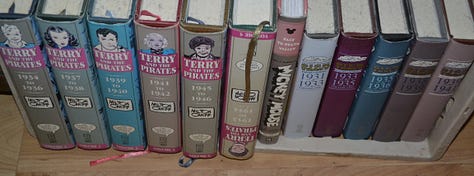

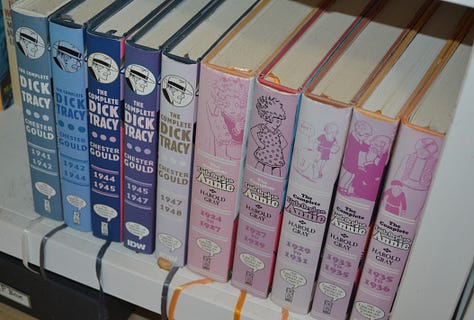

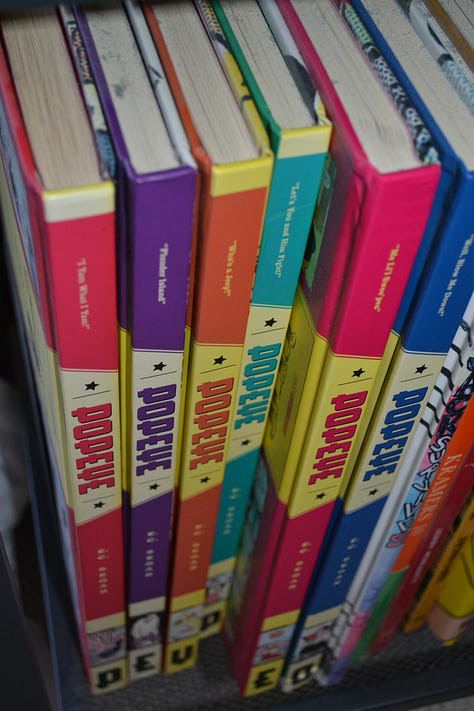

How much if any of that is the result of “The 100 Best Comics of the Century” seems like a question worth asking—so I shall. A big part of the list was devoted to old comic strips from the first half of the 20th century, which for the most part were only accessible to obsessives (like me) who would spend hours at libraries reading the old comic strips in microfilm newspaper collections. In short, The Comics Journal produced a list of comics that our readers had no way to read. At the time of the list, a few publishers had published collections of some of the old strips, but the ability for interested readers to read the classics was seriously limited. But now readers can easily get tons of comics classics that weren’t easily available before the List was compiled, as the shelf porn below attests.

Part of the task of developing a canon is to make the items in the canon available. In our case, to become available means that some publisher agrees to spend the considerable time, effort, and money needed to publish these books, and before any publisher will risk that, it needs some idea that people somewhere are going to be interested. But if the leading art magazine of comics says Dick Tracy is a classic of the art form, a publisher might be encouraged to take a chance and release many hardcover volumes collecting the comic. If it can be said that the List had any influence on getting these classics back in print, it has accomplished something important.

After his tenure as editor of The Comics Journal was done, Spurgeon remained in comics, first producing a comics newsletter, The Comics Reporter, then founding the Cartoon Crossroads Columbus (CXC), a comics festival associated with The Billy Ireland Cartoon Library & Museum in Columbus, Ohio. Even his last gig was about canonizing comics. He died at the age of 50, a huge loss to comics.

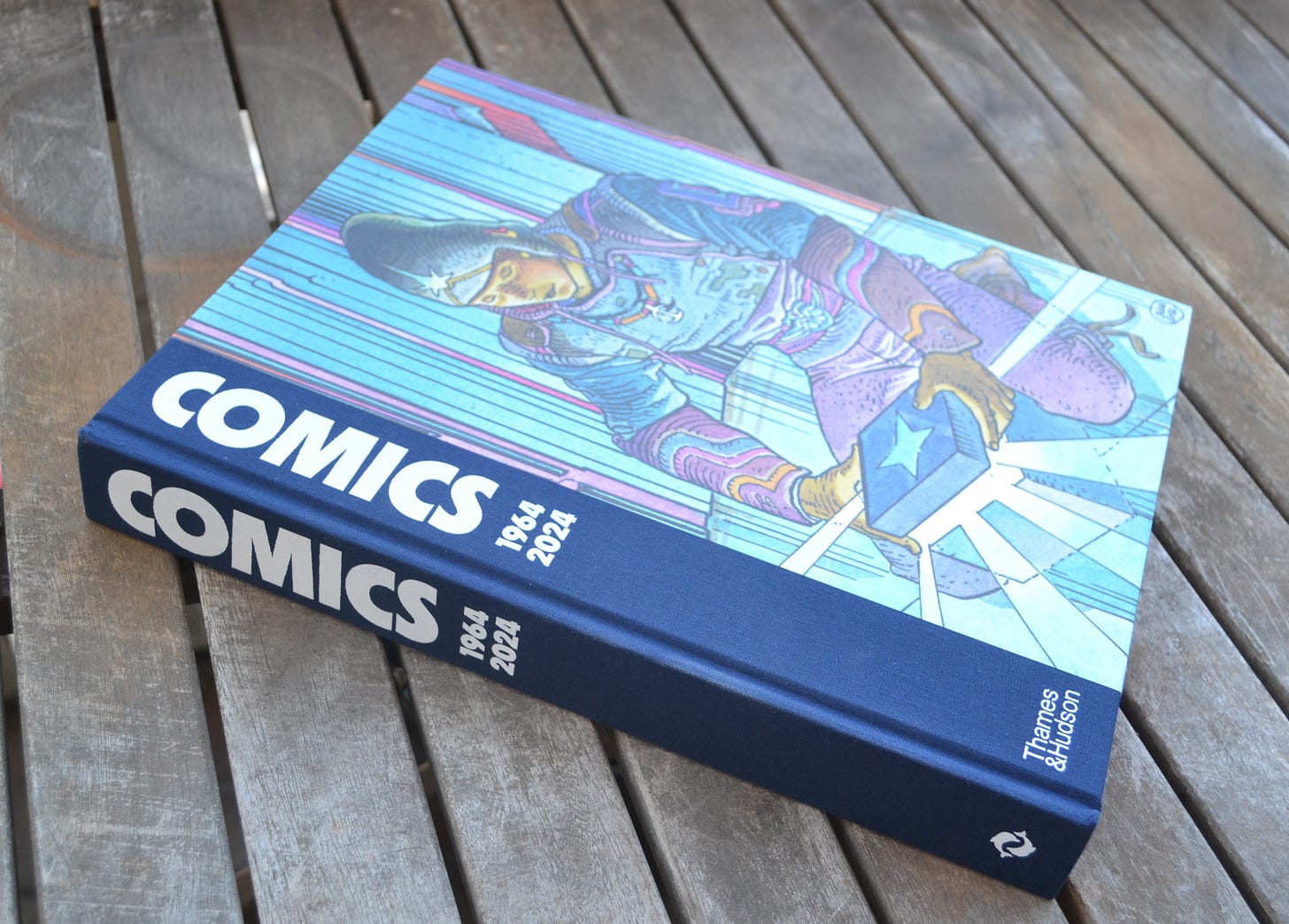

Last year, The Centre Pompidou put on a huge comics exhibit, Comics 1964-2024. That show received a thoughtful review in Artforum. As I was writing this post, my copy of the catalog for that exhibit arrived in the mail. It is a large handsome book. The fact that the most important modern art museum in Paris put on this comics exhibit, and that Artforum thought it was necessary to cover it, and that it is memorialized in a beautiful, scholarly doorstopper of a catalog—this is the world we dreamed of. Thanks for reminding me of this, Colin and Alex.

[Please consider supporting this publication by becoming a patron, and you can also support it by patronizing our online store. And one more way to support this work is to buy books through The Great God Pan is Dead’s bookstore. ]