Novelist Paul Auster wrote his first novel, City of Glass, in 1985. It was a detective novel that fit comfortably into the literary style of postmodernism, a popular approach to making art in the 80s. About ten years after the novel was published, a graphic novel adaptation was published. I can’t remember if I read the novel or the graphic novel adaptation first, but I read them both at around the same time. The adaptation was produced by Paul Karasik and David Mazzucchelli. I’ve always had mixed feelings about “adaptations”, giving more respect to the original version. Thinking about this for two seconds illustrates how absurd this view is—many of the greatest narrative works of art in human history are adaptations of already existing stories. What is Julius Ceasar but an adaptation of one of Plutarch’s Parallel Lives? And even though I know this to be true, the bias I have against adaptations sticks with me.

This adaptation was made with Auster’s participation, a practice that feels appropriate but which in no way guarantees that the adaptation will worth reading. It just means that the adaptation won’t take too many liberties with whatever the author considers to be essential aspects of his original work. But sometimes taking liberties is what makes an adaptation work, or at least prevents it from being a sterile copy of the original.

The story of this adaptation is that in the early 90s a San Francisco book editor, Bob Callahan, was trying to start a line of books that would capitalize on the growing fad for graphic novels. He had an idea of doing a series of adaptations of interesting contemporary noir novels, and decided that he should consult with Art Spiegelman on the project. Callahan was ambitious enough to realize that he didn’t want to just hack these things out, and Spiegelman had drawn the most highly regarded book to appear out of this new graphic novel movement, Maus. Spiegelman was also a gifted editor with his ears to the ground for many of the most talented and interesting comics artists and writers. Callahan and Spiegelman both agreed on adapting Paul Auster, though Spiegelman was somewhat doubtful still because City of Glass is not a very visual novel. “It lives in its sentences,” he said in an interview later about the adaptation.

Paul Karasik had been an assistant to Spiegelman during his editorship of RAW and by coincidence had taught Auster’s son in prep school. Karasik had already put considerable thought into how City of Glass might be told as a graphic novel. He was clearly someone to be brought on board.

Karasik could certainly have drawn the adaptation. He is a skilled cartoonist, but they decided to bring in a ringer, David Mazzucchelli. Mazzucchelli was mainly known for his work on Daredevil and Batman comics written by Frank Miller. He came from a totally different comics world than Karasik and Spiegelman. However, shortly before getting hired on to City of Glass, he produced three issues of an experimental comics magazine called Rubber Blanket (named after a part of offset lithographic printing presses). I was mighty impressed by Rubber Blanket, which made me anticipate City of Glass highly, despite whatever reservations I had about adaptations in general.

The story opens with a bunch of fragmentary images of a man names Peter Quinn, a hack detective novelist, receiving a mysterious phone call. A mysterious phone call is a good way to start a detective story, no? The caller is trying to reach “the Paul Auster Detective Agency.” When the same person calls again the next night, Quinn decides to play along. He visits the caller the next day, pretending to be the detective, Paul Auster. The caller was a disturbed man named Peter Stillman. He believes that his father, who has just been released from a mental asylum, will attempt to kill him. Quinn is told this by Peter Stillman’s wife, Virginia. Quinn dives into the assumed persona of a tough guy private eye with gusto. Quinn uses his knowledge of how a detective should operate—knowledge gained from imagining detectives and writing stories about them—to fake it.

Mazzucchelli draws the scene (and indeed the whole book) in an inky, cartoony style. The work is a little stripped down compared to his work on Daredevil: Born Again. Figures are blockier and the chiaroscuro is cranked up.

The sequence above initiates a nine-page monologue by Stillman, which Mazzucchelli depicts as issuing directly from Stillman’s throat. In each panel, Stillman’s words are depicted as emanating from some metaphorical object—a shower drain, a old fashioned water well, a bird, an antique ferry man, a pile of shit, etc. Making a monologue visually interesting is a challenge for a cartoonist. (A very different but equally great comics monologue is “American Splendor Assault the Media”, in which Robert Crumb draws Harvey Pekar berating his readers for several pages.) Stillman’s words drifting up from his mouth like smoke is a powerful way of drawing word balloons, and reflects the difficulty of adapting a very literary work into a visual narrative medium like comics. This is an ongoing challenge for Karasik and Mazzucchelli, and they come up with various ways to depict words and sentences visually.

This page plays with the nine-panel grid employed throughout City of Glass. Fairly early in the history of comics, cartoonists realized that panels—the little boxes drawn around an image in comics—are arbitrary. They were initially devised to show a series of actions. But here nine panels are laid over an action frozen in time—Quinn writing notes that depict his growing madness.

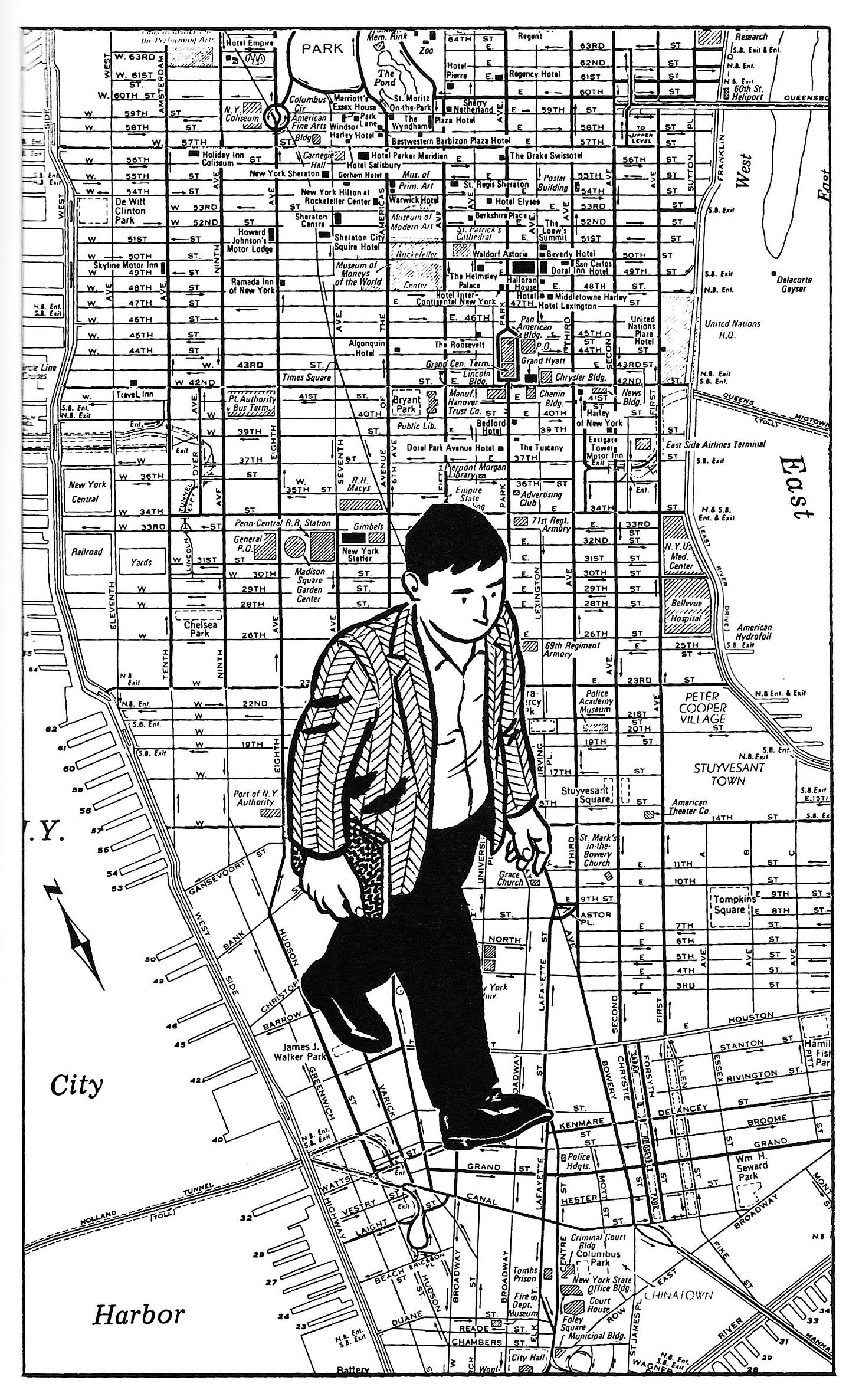

Stillman’s father is also named Peter, and Quinn begins following him on his seemingly pointless wanderings around Manhattan. Stillman the father was an eccentric scholar, obsessed with Paradise Lost and an associate of John Milton named Henry Dark, who immigrated to America and wrote a pamphlet called “The New Babel.” Dark theorized that isolation could provoke a pilgrim to speak God’s language, and Stillman apparently tested Dark’s theory on his own son, raising for years in a darkened room, never speaking to him.

Quinn is puzzled by Stillman’s seemingly random strolls, but he carefully follows him and records them. He draws maps of Stillman perambulations and realizes that Stillman has been spelling out letters with his path—letters that would only be visible to God (or to a detective carefully mapping his path). Over 15 days, Stillman spells out “THE TOWER OF BABEL”

Stillman the father makes no effort to contact his son and seems not to be particularly dangerous, so Quinn makes contact. Not surprisingly, Stillman’s motives still seem obscure even when he carefully explains them to Quinn.

Quinn is drawn deeper into Stillman’s bizarre project. He becomes obsessed, and freaks out when Stillman abruptly disappears.

At his wit’s end, Quinn decides to contact Paul Auster of the Paul Auster Detective Agency. Maybe if he can figure out how Auster is involved with the Stillman family, he’s understand the elder Stillman’s bizarre project. But Auster is not a detective—he is a writer. As the two have a conversation, Auster’s son Daniel runs into the room. (Curiously enough, Karasik taught the real Daniel in prep school.) Auster has no idea who the Stillmans are or why they thought he was a detective.

At this point, Virginia and the younger Peter Stillman disappear as well. They no longer answer their phone calls. But Quinn has developed an insane connection with this “case”. His job is to protect Peter Stillman from his father, so he will continue to do it. He stations himself outside Stillman’s apartment building, watching the front to make sure the older Stillman doesn’t attack.

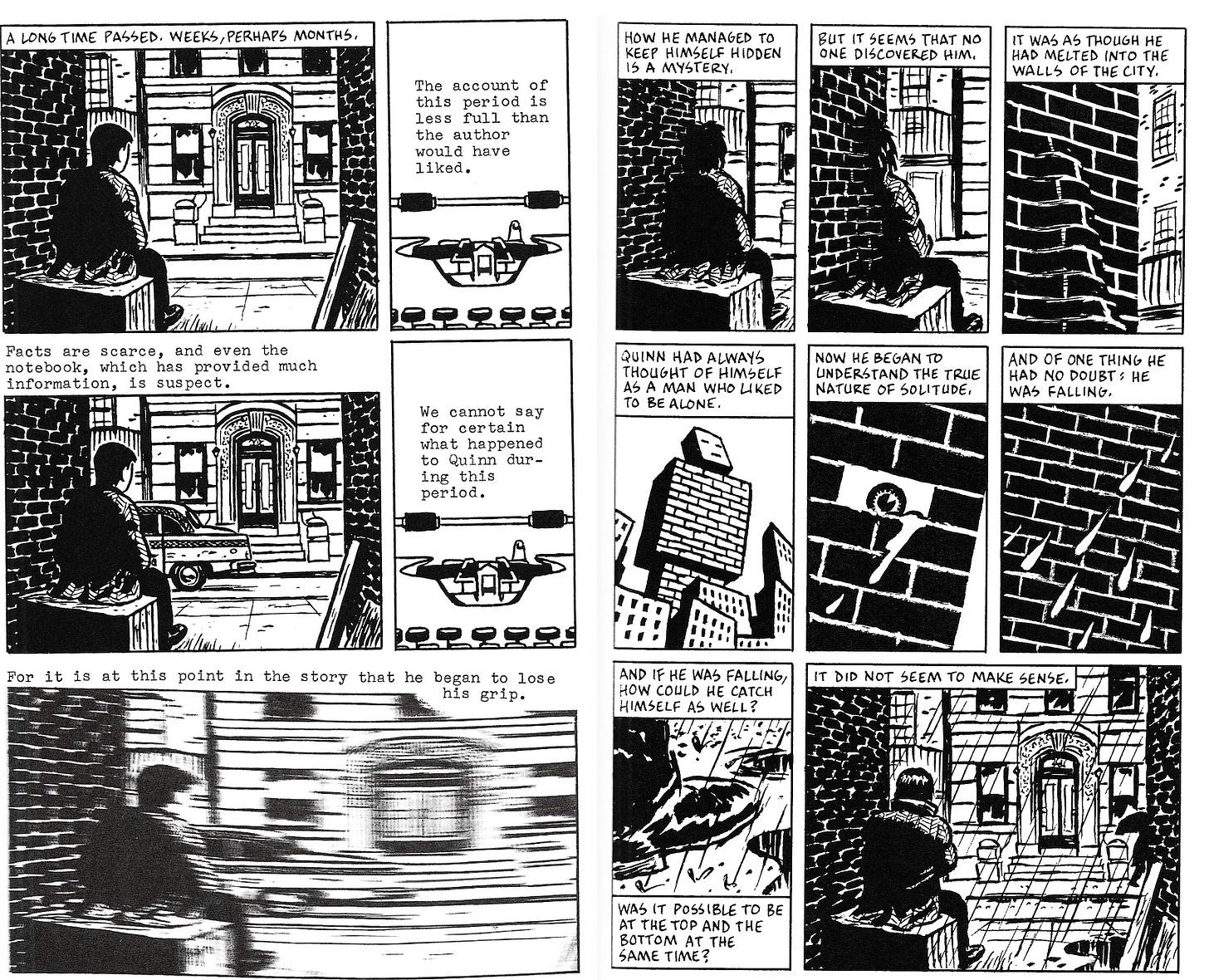

At this point we have a series of pages showing Quinn waiting in an alley in front of the Stillman’s building. He gradually disintegrates, becoming day by day a disheveled street person. Mazzucchelli and Karasik show this disintegration in a variety of ways: streaking in a way that must have been made on a photocopier, and sinking physically into one of the brick walls that lines the alley.

After a long time, he returns to his own apartment, only to find someone else living there. Quinn had apparently staked out the Stillman’s apartment for months without noticing the passage of time. He is gaunt, wearing shaggy, unkempt hair and beard, and has been driven insane by this “case.” He staggers back to the Stillman apartment, goes inside, and finds it not only uninhabited, but completely stripped bare. In the end, he scrawls in his notebook and presumably perishes from the world.

Shortly after the graphic novel version of City of Glass was published, the Neon Lit series that Bob Callahan was spearheading folded. City of Glass soon went out of print. Spiegelman has remained active in the decades since, but not very prolific. Auster died last year after writing 19 novels and many non-fiction books. Mazzucchelli’s best-known work subsequent to City of Glass was Asterios Polyp, an academic comedy that reads as if David Lodge had decided to make a postmodern comic book. Karasik has primarily been an educator since City of Glass. He drew an interesting family memoir, The Ride Together, and with fellow cartoonist Mark Newgarden wrote one of the most ambitious works of comics criticism I have ever read, How to Read Nancy. And this year, Karasik brought City of Glass back into print, pairing it with new adaptions of Ghosts and The Locked Room, the other two books in Auster’s New York Trilogy of postmodern detective novels.

Karasik wanted to collaborate on adapting Paul Auster again. In Ghosts, he teamed up with Lorenzo Mattotti (who was the subject of the fourth entry in the 100 Comics series), and drew The Locked Room solo. This was an brave choice because in a collected volume like this, he is placing his rather ordinary drawing skills against two utter geniuses.

And to bring this project back to Art Spiegelman, when Penguin published a collected edition of the prose version of the New York Trilogy, Spiegelman painted the cover.

Furthermore, I am of the opinion that Trump must go.

[Please consider supporting this publication by becoming a patron, and you can also support it by patronizing our online store. And one more way to support this work is to buy books through The Great God Pan is Dead’s bookstore. ]

where possible and interested, you might as well check the titular album also based upon Paul Auster’s, by Daniel Bernardes and co.