Cosmos

A Fascinating Footnote in the Art History of Houston

In December, I took a trip to one of Houston Public Library’s periodic book sales. I picked up a few books, including a 1923 high school yearbook from Central High School in Houston. I piled my book haul into the back seat of my car. Apparently the yearbook fell out of the paper bag holding the rest of the books I bought that day. Between that moment and a couple of days ago, that yearbook has sat on the floor of my car. I had forgotten I bought it. But yesterday I rediscovered my copy of Cosmos and finally took a look.

I have to say that Cosmos is an exceptionally cool name for a high school yearbook. (My high school’s yearbook was called Reata, Spanish for lariat. Our sports teams were the Mustangs.) Central High School was one of Houston’s first high schools, and in 1923 was located in downtown Houston, on the block that almost 100 years later would become the site of the High School for the Performing and Visual Arts. That city block is currently nestled among the skyscrapers of downtown, but downtown Houston in 1923 must have been a very different place. Central High School was segregated, for one thing. Flipping through the pages of Cosmos, one sees a 100% white student population. In 1923, the only high school for black Houstonians was called Colored High and was located only 15 blocks away from Central High School.

I didn’t have any particular expectations when I opened the 1923 Cosmos. I wanted to look at the fashions worn by 1920s teenagers, their preferred hairstyles, their clubs, their sports—all of high school life that Cosmos saw fit to print. I also scanned the students’ names, to see if any familiar figures from Houston history jumped out. I found Iva Farenthold, who may have been related to the prominent local political family that produced Sissy Farenthold and the disgraced Blake Farenthold, and Frances Sakowitz, who must have belonged to the family that owned the now defunct Sakowitz department stores. I used to get my school clothes from Sakowitz.

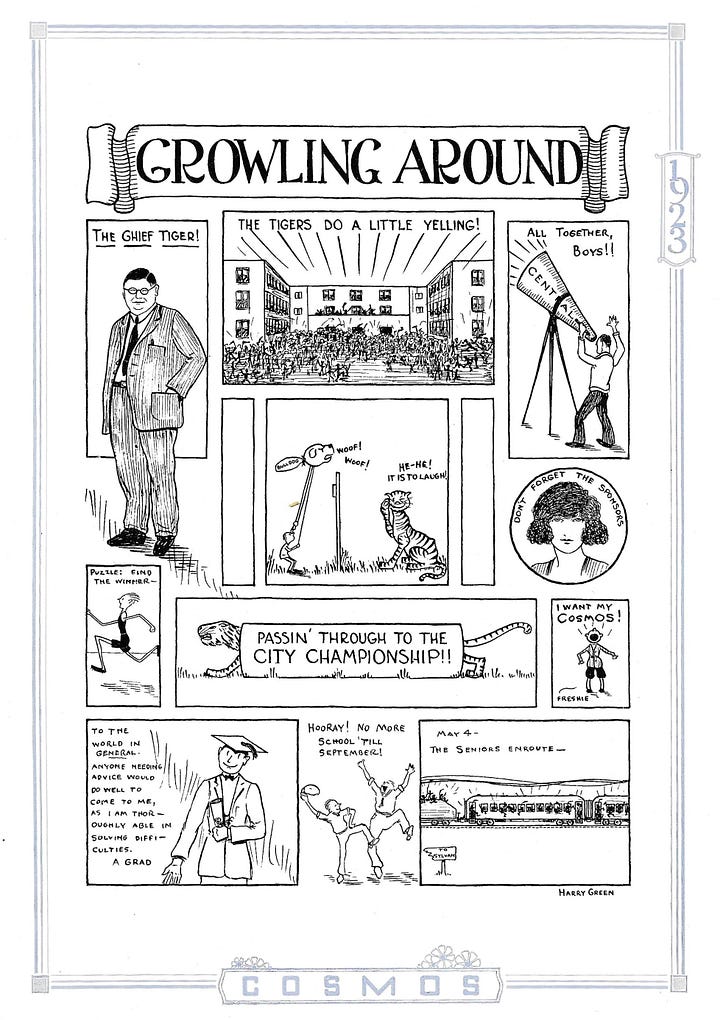

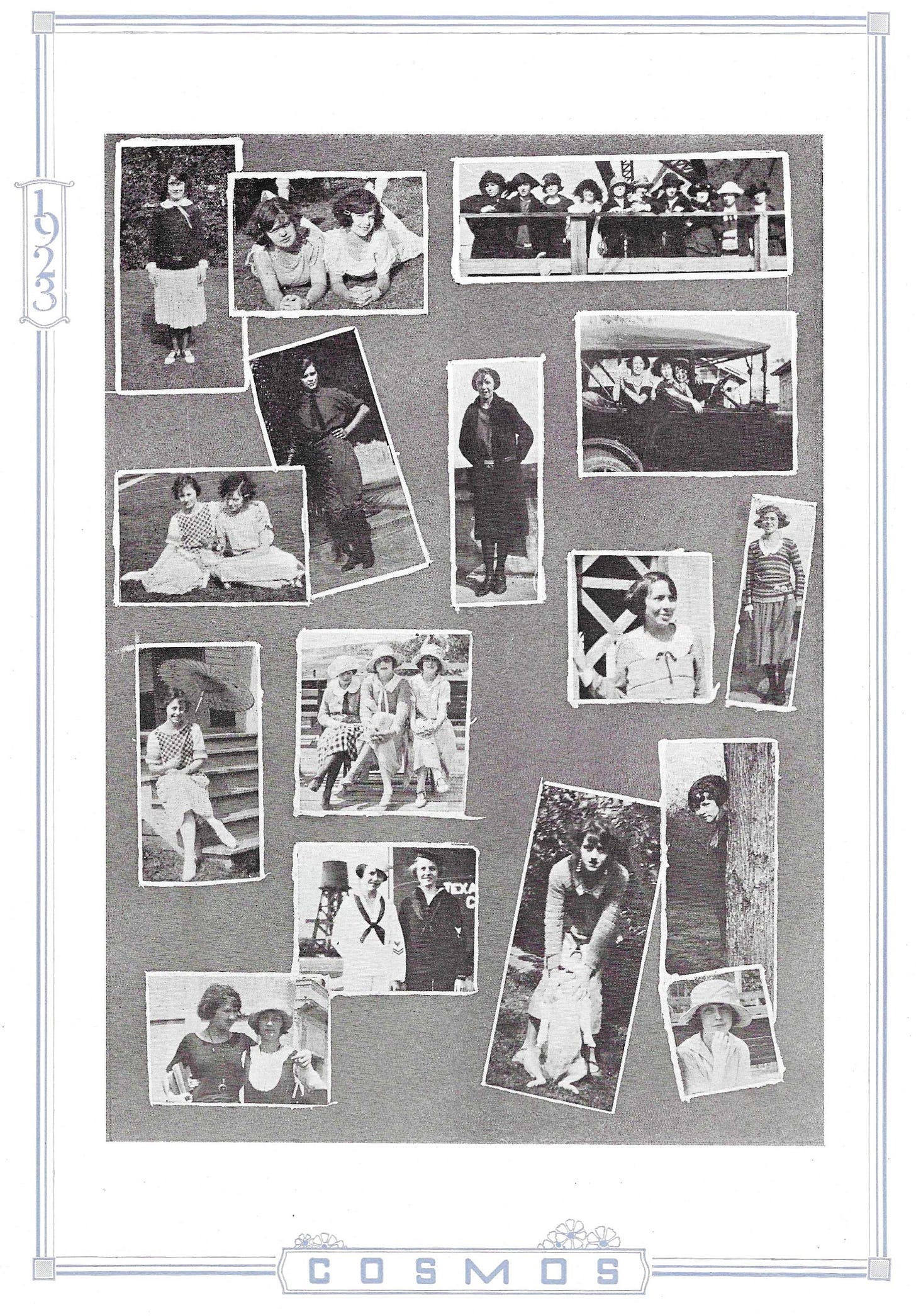

Cosmos is divided into six sections that they call “books”. Book I is dedicated to faculty, book II to the students organized by grade, book III to organizations, book IV for “favorites” (basically the four favorite girls of the class of ‘23), book V is for athletics, and book VI has the intriguing name “Tiger’s Claw.” Tiger’s Claw is a collection of jokes, cartoons drawn by students, and photos of various social activities—including a bunch of cute, fun-loving flappers in amazing fashions. I love the pair in sailor suits.

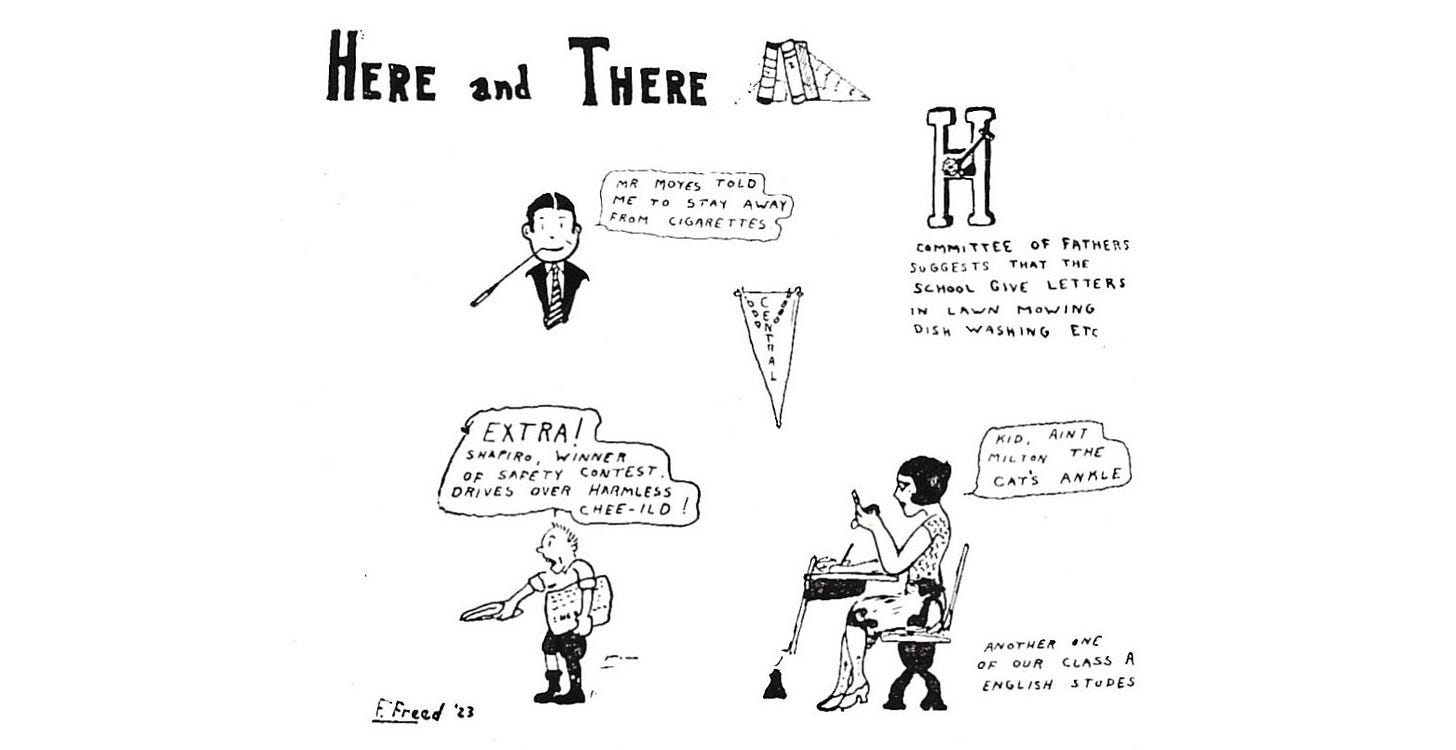

The presence of flappers at Central High School was not uncontroversial, as seen in the following cartoon in the Tiger’s Claw section.

Notice the initials of the cartoonist—F.H.F. They are short for Frank H. Freed, then a senior at Central. (I’m not sure what the “H” stood for.) Frank Freed was an early supporter of arts in Houston and an extremely talented “Sunday painter.” Stumbling across his senior yearbook is a real find as far as the art history of Houston goes. This discovery will make Randy Tibbits jealous.

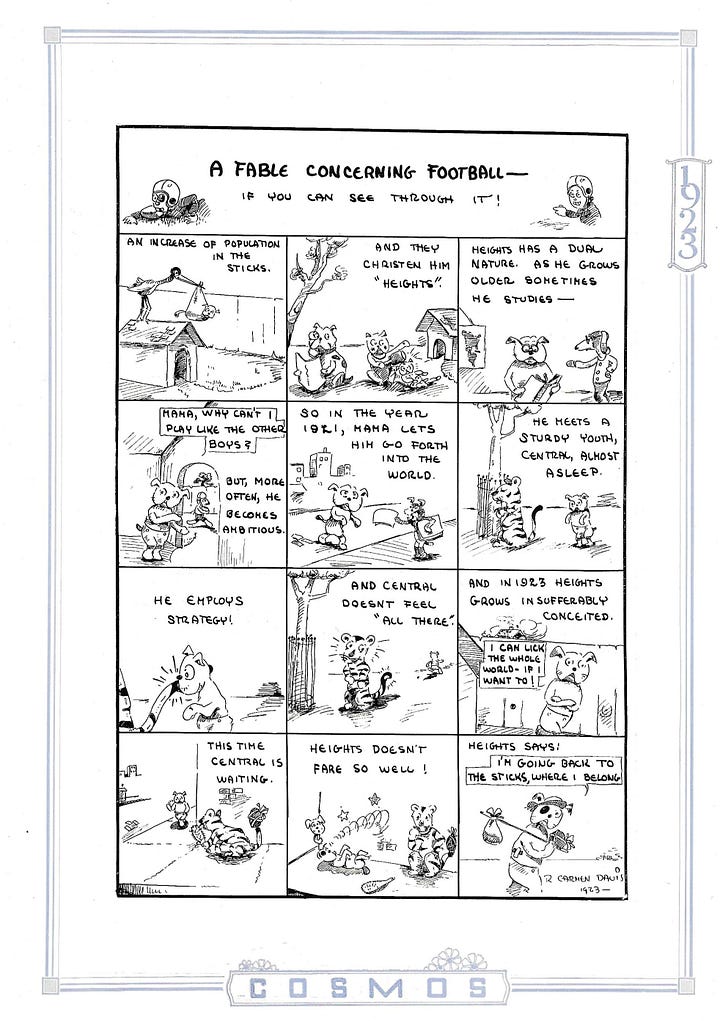

Freed was not an athlete at Central (at least his picture didn’t appear on any of the teams), but high school football was a big part of Central High life, and his cartoons reflect that. I suppose this is an accurate representation of the team’s jerseys, pants, and helmets, but can’t be sure. In all the football team photos in Cosmos, the players are dressed in shirts and ties. If Central’s team were the Tigers, the bands on their arms could be their stripes.

In this small selection of gags, I think Shapiro is Mollie Shapiro, a girl in Freed’s class, and Mr. Moyes is the dean of boys and a fairly strict looking character, going by his photo in Cosmos.

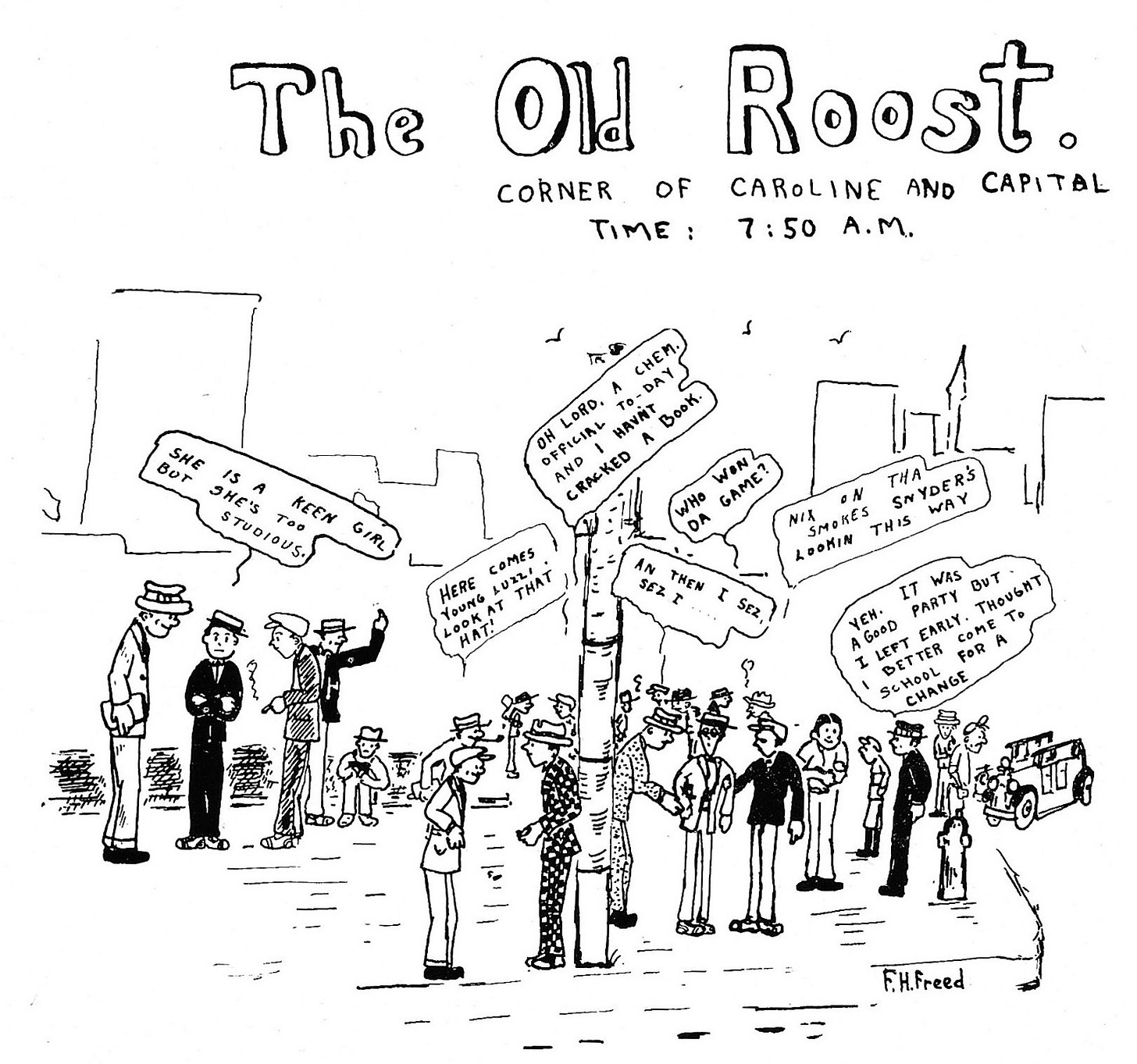

This is my favorite Freed cartoon in Cosmos depicts a gang of boys smoking in front of the school before classes. One boy warns the others about smoking because “Snyder’s lookin this way.” There was a senior girl at Central named Blanche Snyder—was this a dig at the class busy-body? Smoking if forbidden was not a hanging offense—otherwise Freed wouldn’t have felt free to draw his classmates with their cigarettes and pipes blazing for the yearbook.

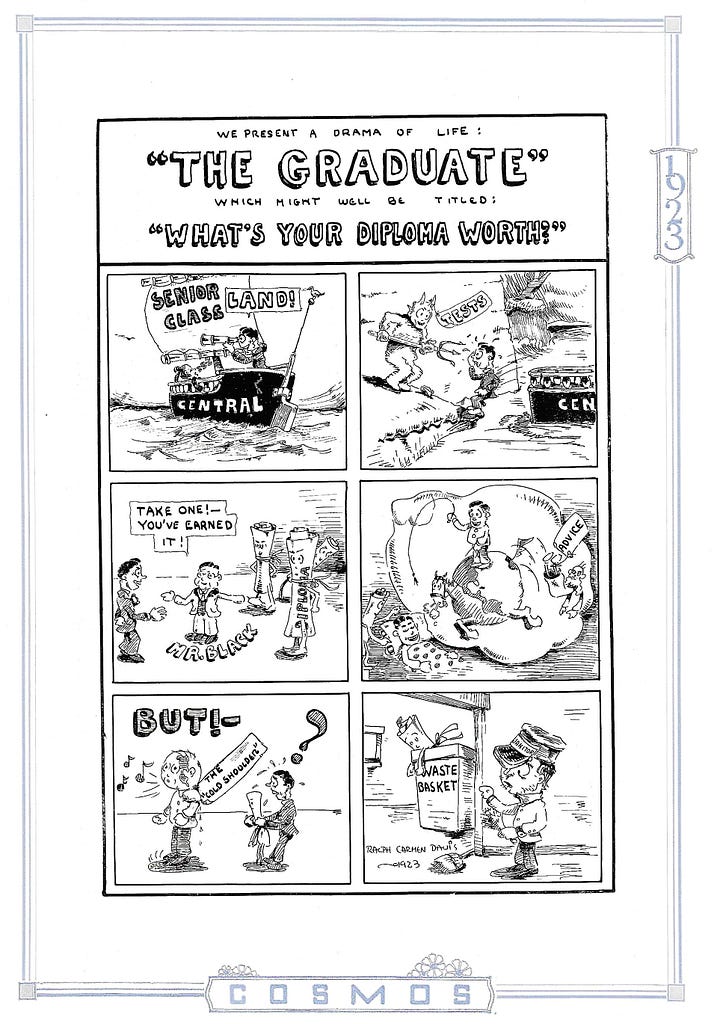

At this point, you may be excused for thinking that Frank Freed was not a particular gifted cartoonist. He wasn’t even the best cartoonist at Central High. The other cartoonists in the Tiger’s Claw were Harry Green and Ralph Carmen Davis, both of whom exhibited serious cartooning talent.

According to art historian William Camfield, who wrote a biography of Freed in the introduction to his book More Than a Constructive Hobby: The Paintings of Frank Freed, Freed continued to draw cartoons after he enrolled at Rice University. Camfield writes that Freed transferred to Harvard after his freshman year due to an antisemitic incident. And at that point, nothing is known of his artistic activities until after World War II. Freed discovered fine art in 1947 when he was “floored” by an exhibit of Ben Shahn paintings at the Museum of Modern Art in New York.

In 1948, his wife encouraged Freed to take painting lessons. He took a design and painting class at the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, taught by Robert Preusser. Freed and the Museum of Fine Arts have had a close relationship—the MFAH has 10 of Freed’s works in its collection. A painting of a bored museum guard was hanging in The Fabulous Fifties: Houston Art at the Dawn of the Space Age, 1945-1961, an exhibit that literally just closed today.

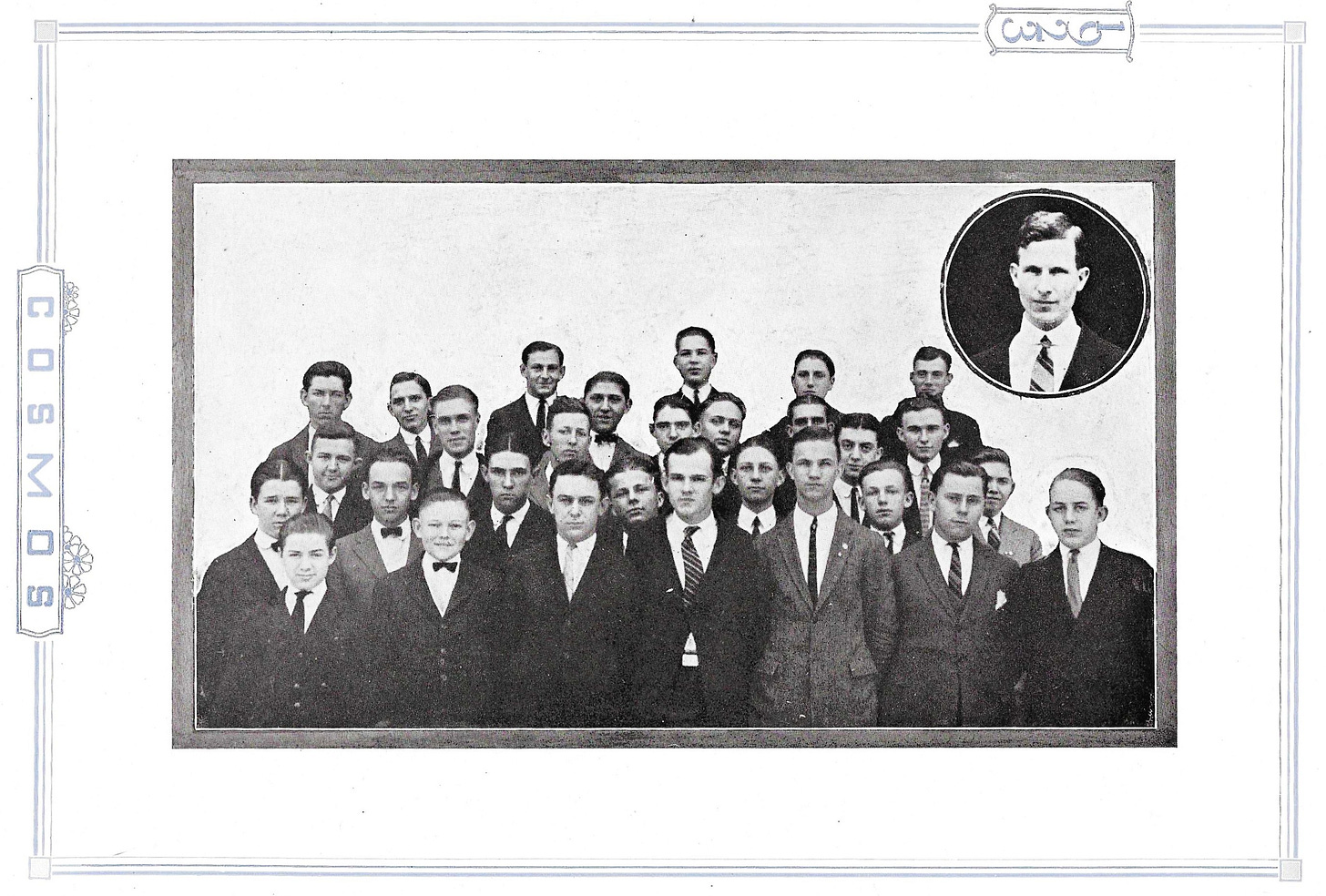

This was the Jeffersonian Debating Society. One of these boys was Frank Freed—I think it may have been the tall thin boy on the front row. That looks close to a photo of Freed from his 20s published in More Than a Constructive Hobby.

Confrontation is one of Freed’s paintings that is in the collection of the Museum of Fine Arts. It feels unusually timely.

Furthermore, I am of the opinion that for the good of America, Trump must release everything related to the Epstein case (unredacted), disband ICE, and resign.

[Please consider supporting this publication by becoming a patron, and you can also support it by patronizing our online store. And one more way to support this work is to buy books through The Great God Pan is Dead’s bookstore. ]

Fantastic archival find. The progression from those early cartoons to Confrontation shows how foundational work doesn't always look polished but lays crucial groundwork for artistic vision later on. I think what makes this discovery valueable is not just finding Freed's juvenilia but seeing how someone moved from institutional gag panels to politically engaged painting after a 25-year gap. The antisemitism angle at Rice probabley played a bigger role in that shift than people realize, the long pause before MoMA floored him fits too well into that narrative. Real gems hide in car floors sometimes.

One of the 1923 Cosmos cartoonists that you mention, Ralph Carmen Davis, was my great uncle by marriage. I was pleased to see your post about his high school work because I don't know much about his early life. You've inspired me to dig deeper.

RCD went on to Rice Institute, (where he met my great aunt) and I believe he contributed cartoons and drawings to the Campanile yearbooks. I'm not completely sure, because they aren't attributed, but they resemble some of his other drawings that I have. He also contributed poetry and other writings to bound volumes of student work.

He lived in central Houston for the rest of his life; I remember him as something of a bohemian non-conformist. He was a photographer, calligrapher, and amateur filmmaker. One of his sources of income was hand-lettering the names on student diplomas.