I started writing this newsletter in 2009, and from the very start, one of the most exciting art venues I visited was Box 13. Box 13 was founded in 2008 when artists were evicted from Commerce Street Artists Warehouse. Last Friday, I attended their latest opening—four exhibits by four artists, Jonas Criscoe, Mateo Gutiérrez, Cassie Gnehm, and Alexandria Canchola. All four artists were impressive, and I was especially moved by Mateo Gutiérrez’s very political It’s the End of the World As We Know It. All of these artists deserve thoughtful reviews, but today I want to talk about Fruits of Their Labor by Alexandria Canchola.

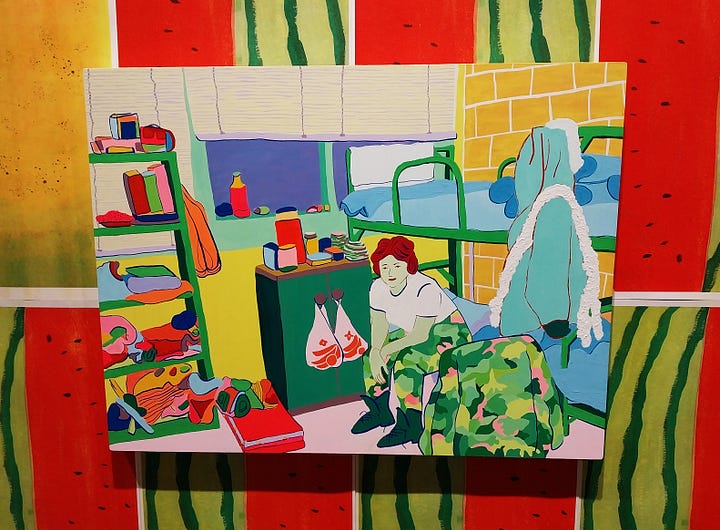

Canchola’s exhibit combines an installation—Canchola has built a colorful kitchen against the back wall of the gallery and a reproduction of a dorm room in the middle of the gallery—and paintings along the walls. The result is an playful, intensely colorful exhibit. Canchola’s intent is to honor her grandmother and aunt—it is a very sentimental, nostalgic body of work.

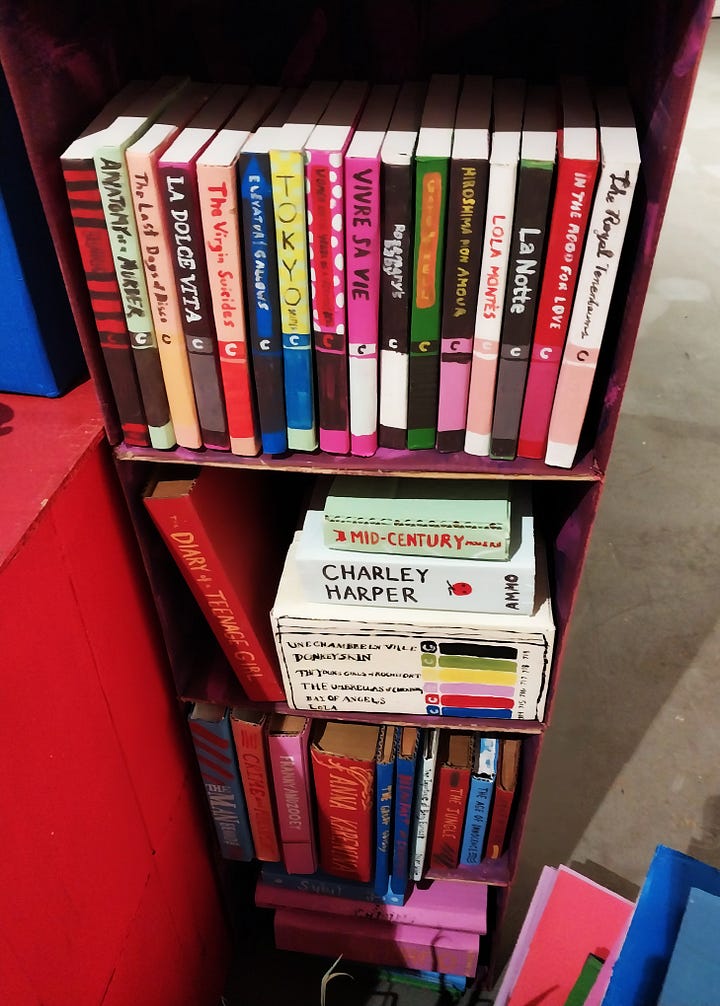

The image above is what I take to be the corner of a dorm room—with desk (with a small bookshelf right next to it), a file cabinet, a chair and a record player. The intense colors of the desk and file cabinet make me wonder if these colors resemble the actual dorm room depicted, or if Canchola decided to add them to give the installation an animated cartoon esthetic. I assume that each installation represents an important space for either her aunt or grandmother, but I don’t know who to assign the dorm room to.

I’m going to assume that this is the aunt’s room—for no particular reason. But the spaces that Canchola builds out of corrugated cardboard and flat bright paints seems to describe a specific person so well that it feels right to assign the dorm room to someone. The books, records, and DVDs here seem to reflect a young woman learning about culture—the books and DVDs are the kind one might encounter in survey classes of literature and cinema. I was heartened to see a book by a cartoonist, Diary of a Teenage Girl by Phoebe Glockner, present. Why there are five different copies of Little Women piled on top of her bookshelves, I can’t imagine.

For some reason, I have always been drawn to artists who make somewhat crude approximations of real things. I think of artists like Conrad Baker, Tom Sachs, or Claes Oldenburg. Like Baker, Canchola produces life-size simulacra of the rooms that interest her but somewhat cruder than the real things. It also makes one think of so-called cargo cults. These arose on Melanesian islands that were used as airbases in the second world war. Tribesmen would see soldiers engaging in mysterious activities, which would be followed by airdrops of supplies. They concluded that if they performed these same rituals—which included fabricating non-functioning duplicates of the equipment the soldiers were using—they would get airdrops, too. This was a premodern people witnessing modern activities and concluding these activities were a kind of magic that brings good things to them. In a sense, Canchola is performing the magic rituals to bring back the two women who are the subjects of this exhibit. (Producing art is engaging in the practice of magic.)

The other installation is a kitchen. This is not the idea of a kitchen, but a kitchen current in use—a television on the kitchen counter is on; there are dishes in the sink. And I assume that this is a gathering place—it is both about preparing food and socializing.

The colors remind me of an animated cartoon. One could imagine the Flinstones or the Simpsons eating here.

I like the dishes in the sink because you don’t even see them until you get close. The colors again seem to intense to be realistic—the bright orange trim angainst the royal blue cabinet doors feel like Moorish tile-work.

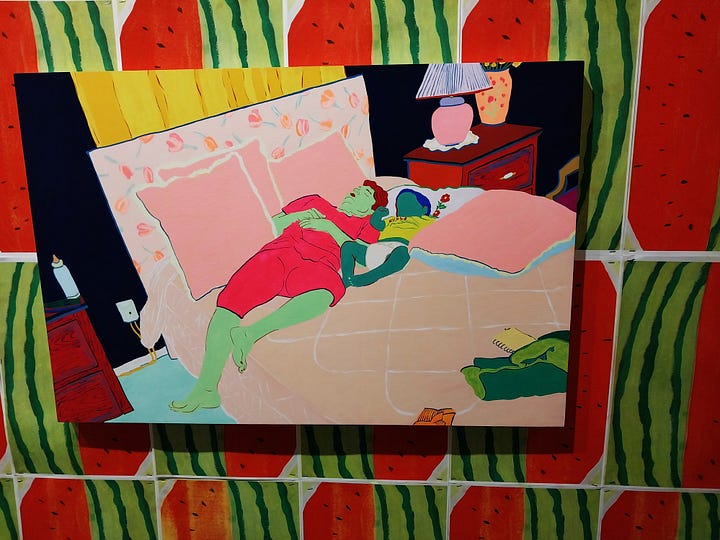

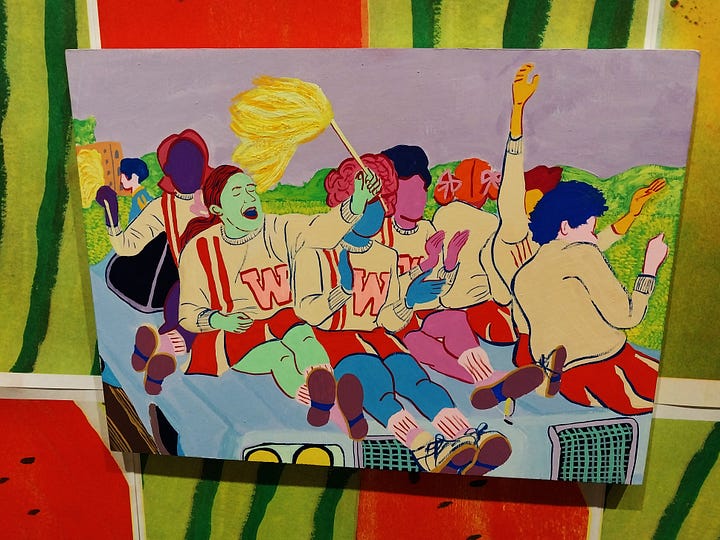

The paintings depict images that feel like snapshots. I don’t know if Canchola used actual family snapshots as her source material, or if she just composed snapshot-like images without photo-reference.

Although space the figures inhabit and their poses feel like they were caught on the fly, Canchola simplifies the images into flat areas of color with visible outlines. None of the colors feel particularly natural—the paintings have a poster-like boldness. They suggest an artist who comes out of a design and illustration background.

The paintings are hung on a wall against a background of melons and papaya. The exhibit has a jaunty topical vibe. The two women may have tropical roots, but the pictures depict cliches of American life—military service, a pep rally, a retirement party. The exhibit is not overtly political (unlike Mateo Gutiérrez’s searing It’s the End of the World As We Know It upstairs), but seeing it, I couldn’t not think about the anti-immigrant hostility in the U.S.A. today. In a country where the dominate political group wants us to view Latinas as foreign invaders, Fruits of Their Labor asks us to see them as fellow citzens.

Alexandria Canchola is an art professor at Texas A&M Corpus Cristi, and she appears to be a successful freelance illustrator as well. Her work is both commercial (Tecate was one of her clients) and political (lots about immigration). Fruits of Their Labor is a personal work about Canchola’s family, but its political valence is there if you want to see it. It very gently and lovingly screams at you—we belong here just as much as anyone else.

[Please consider supporting this publication by becoming a patron, and you can also support it by patronizing our online store. And one more way to support this work is to buy books through The Great God Pan is Dead’s bookstore. ]