Today I decided I need a new belt, so I went to the Jos. A. Bank at the corner of University and Kirby in the Rice Villages shopping area. This was the location of a huge Half Price Books and Records when I was an undergrad nearby at Rice.

I was unable to shop at this Jos. A. Bank because when when hurricane Beryl hit Houston in July, the sign on the roof of the building was blown over, causing major damage to the building. Until January 2020, this had been the location of one of my all time favorite bookstores, Half Price Books. Over the decades, I had probably spent hundreds of dollars buying books here, and many many hours exploring the shelves there. This Half Price Books location had been open in the Village since 1981, the year I graduated from high school. It was perfect for me since I soon started attending Rice, which is within pretty easy biking or walking distance from campus.

Half Price Books is a chain out of Dallas. It was formed as a used book store in a former laundromat in 1972. It has expanded hugely since then. They still sell a lot of used books, but a large part of their stock is from publishers remaindering titles. (Remaindering is a practice in the book trade in which a publisher sells off excess inventory of a given title.) They now have 116 stores in 19 states. Texas has 38 stores, followed by Ohio with 12. For some reason outside of Texas, the Midwest has the greatest number of stores. But Washington state has seven, which comes in to play below.

When I was in high school and got my driver’s license, two of the places I suddenly had access to was the River Oaks theater and a Montrose Half Price Books, located on Waugh in a defunct church building. The fact that automotive freedom for me meant better access to book and record stores and cooler movie theaters shows what an artistic little nerd I was back then. Mostly I was shopping for records when I went to the Montrose Half Price Books. They sold old LPs so cheap that I could find one with a cool cover and buy it without having any idea if the music inside was good. In the end, my conclusion is that this is a terrible way to find new music, but at least one album purchased using this selection method has gone on to be one of my life-long favorites: Exotic Birds and Fruit, the 1974 album by Procol Harum.

That wasn’t the best album I bought there. The best was when around 1980 or 1981, I was idly flipping through the LPs and came across a best-of compilation of the Velvet Underground. This was one put out in 1970 by Verve.

I didn’t know much about the Velvet Underground, but I had read about them in Rolling Stone magazine and I knew they had an important reputation. For $3, that was enough for me to try them out. I brought my prize to the 20-something clerk who took one look at it and said, “Goddammit! How did this get out on the shelves?” As I would learn later, the people who worked at Half Price always had first pick.

Then when I started going to Rice, especially when I moved on campus, my loyalty was transferred to the Rice Village Half Price Books and Records. By then, I was less about digging up obscure LPs and more about exploring the stacks for cool books, It was at this Half Price that I found one of my most prized art books.

The Machine was a thematic art exhibit about the idea of “the machine” and arts many responses to it over the centuries. It was held in 1968, put on initially at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, then to the San Francisco Museum of Art and the closing location for the exhibit was to be St. Thomas University here in Houston. But at some point in the planning of this exhibit, Dominique and John de Menil famously had a falling out with St. Thomas and transferred their loyalty to Rice (where it stayed until the Menils could build their own museum). What I learned when I bought my copy of The Machine was that the catalog had been printed before all of this happened. The exhibit was no longer going to St. Thomas—it was going to Rice. But the catalog still said St. Thomas. The solution? To print an erratum slip and paste it into the catalog. So in addition to its substantial value as an exhibition catalog, it also inadvertently illustrated a little bit of local art world drama as it was happening.

The Menil issue was not why I bought this book. I bought it because it is an amazing example of bookish technology. Unlike every other book I own, it has a metal cover (I think it is made of a thin sheet of steel—it is magnetic) with brads binding the pages and hinges allowing the cover to be opened.

The curator was Pontus Hultén, and the show was principally about experiments with technology conducted by Western artists from the Renaissance to the modern period, and Hulten was especially interested in depictions of modern technology by such enthusiasts as the Futurists. Looking at this catalog some 40 years after I first encountered it, I had to ask where are the Chinese and Arab mechanical marvels that they produced in medieval times, but this feels like a minor complaint. The catalog is a delight and I wish I could have seen the exhibit, but I was only five when it came to Houston.

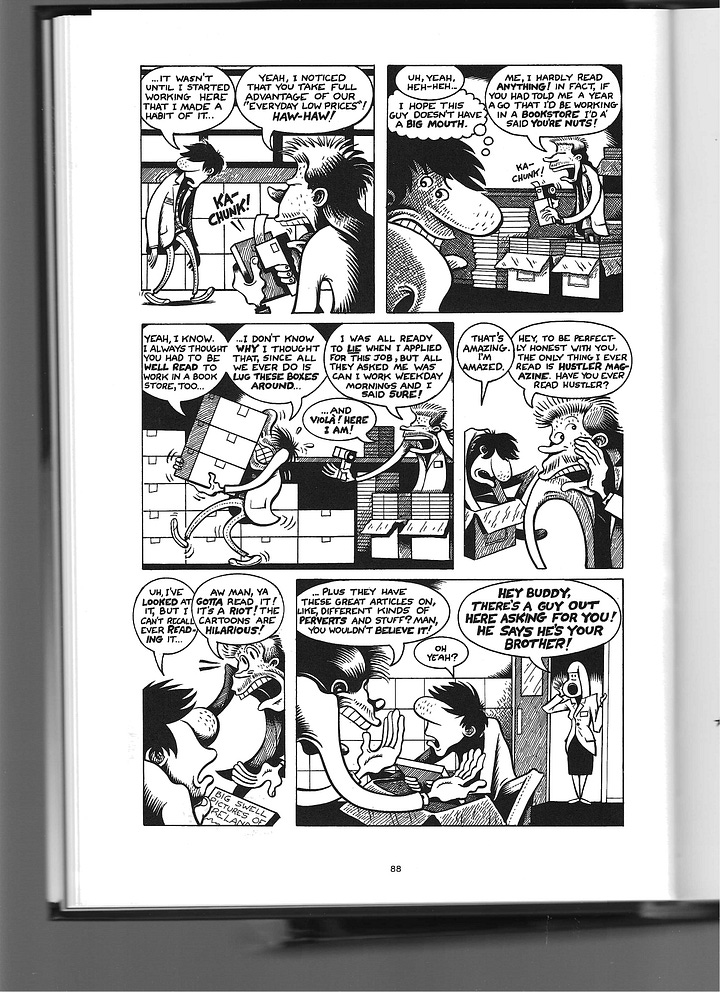

In the late-80s and early 90s, I worked as an editor for Fantagraphics Books in Seattle. Our office was a ramshackle private house north of the University of Washington. A few blocks south of is was another Half Price Books. Seattle was a paradise for booklovers then, awash with excellent bookstores, but that particular Half Price was my neighborhood bookseller. I spent many hours scouring its shelves. It was also the location of a series of stories in Peter Bagge’s Hate, his comic book that we published about Buddy Bradley, a aimless young man living in 90s-era Seattle. Bagge had produced a comic book called Neat Stuff, which was a domestic comedy about the Bradley family. Bagge had sold the owners of Fantagraphics on Seattle as a cheaper place to live than Los Angeles, so a few weeks after I was hired, the whole company relocated. For some reason, Bagge chose that moment to end Neat Stuff, age the character Buddy Bradley from teenager to young adult, and change the location from suburban New Jersey to Seattle. The timing was exquisite, as a youth culture was just about to explode out of Seattle, and Bagge got to place his main character Buddy right in the middle of it.

Bagge decided to give Buddy a job at my favorite Half Price Books. It was through Bagge’s depiction of Buddy’s job that I learned of Half Price Books employees habit of picking through the merchandise before it got shelved.

I know that this bookstore was meant to be a now-closed Half Price Books on Roosevelt Way. I assume that Bagge knew about the employee “discount” from talking with people he met working there. In any case, I now knew why the clerk who had to sell me that Velvet Underground record was so annoyed.

Bagge returned to this location later on in Hate when Buddy disastrously gets his girlfriend Lisa a job there.

I’m gutted that there is no Half Price Books near me any more. My guess is that real estate inside the Loop in Houston has simply gotten too valuable for Half Price to rent retail space here. Ditto with Seattle—I’m sure that Roosevelt Way is way too expensive for a used bookstore to rent a space there anymore. The era of the cozy neighborhood bookstore is mostly over.

[Please consider supporting this publication by becoming a patron, and you can also support it by patronizing our online store. And one more way to support this work is to buy books through The Great God Pan is Dead’s bookstore. ]

What a wonderful post. The Machine catalog w metal cover sounds terrific. I do miss the two 1/2 Price Books that were inside 610 loop. Not the same without them nearby. I also like the one in Seattle near UW. They are hardly any old haunts left inside the loop - too high rents? All going corporate? And now charging for parking too. Again, enjoyed your post.

I've shopped at Half Price Books locations since 1979, starting in San Antonio at their lovely Broadway Ave. location by the Zoo and the Witte Museum. I now rather regret the massive amounts of time I spent flipping through record bins and shelves. The internet has given me more convenient ways to waste my time looking through listings of Kindle Books, streaming films, and many other cultural products. HPB was part of the employment market for Houston hipsters similar to what you've talked about in Seattle. There was a constant shuffle of people from HPB to Record Exchange to Whole Foods Market to various bike shops. Some folks got trapped in that cycle forever. Which is better than now, I guess, when young hipsters become baristas or just permanently unemployed.