The art magazine Art Lies was published in Texas between 1994 and 2011. (In 2013, Art Lies merged with Gulf Coast, a literary journal published by the University of Houston.) As an observer of culture, two of my ongoing obsessions are the provinciality of the Texas art scene (i.e., “cultural cringe”) and zines. Art Lies fought against the provincial nature of Texan culture by just existing. Shortly after Art Lies went dark, the University of North Texas started an online, searchable archive of issues of Art Lies on their Texas history website, The Portal to Texas History. I started reading the old issues there, and for a brief period attempted to recap them on this blog. One of the founders of Art Lies was Benito Huerta who is currently having an exhibit with his wife and fellow artist, Janet Chaffee, at Andrew Durham Gallery. He Said, She Said is up through the end of May.

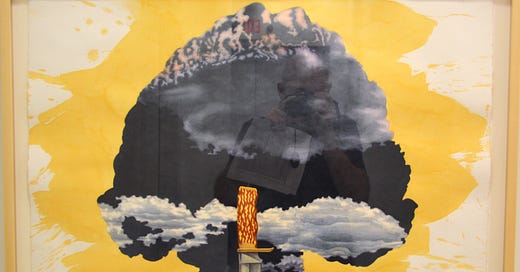

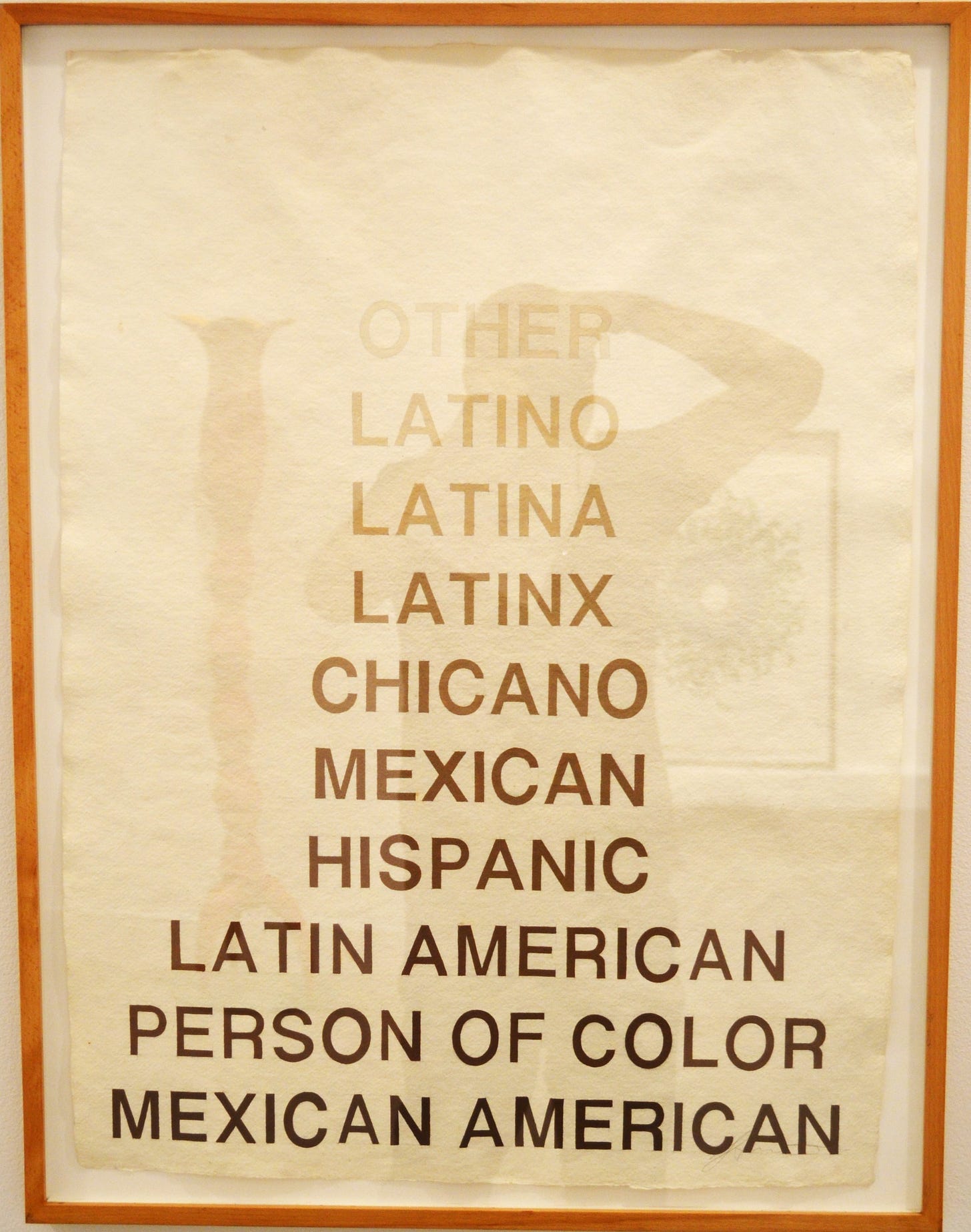

I’ve seen Huerta’s paintings before, notably at an exhibit at the Avis Frank Gallery in 2012, where he took modernist classics like Picasso’s Les Demoiselles d'Avignon or Gaugan’s L'Esprit des morts veille and produced critical pastiches of them. Huerta reminded us of these two most colonialist-minded modernist painters’ implied attitudes toward brown and black people, especially brown and black women, by employing post-modernist strategies of satire and pastiche. The thing about post-modernism is that an artist doesn’t have to exhibit the stylistic tendencies of a particular school—the entirety of art history is fair game. If an idea is best expressed using a cubist or post-impressionist style, then by all means, use it. A post-modern artist like Huerta can produce a kind of macho, van-art image like The Edge of Night or a very conceptual, text-based piece of art like Shades of Brown (Value Scale). The ideas call for different means of expressing them.

Huerta’s paintings of tough guy shit are produced on paper with watercolors. When I think of watercolors, I think of wispy, delicate images composed of layers of transparent color. The medium seems especially well-suited to lovely landscapes and pictures of flowers. Huerta’s crisp edges and violent images of knives, guns and explosions is an ironic use of the medium of watercolor. Pushing a medium to an somewhat unexpected place is also a feature of the art of Janet Chaffee in He Said, She Said.

When I first saw Chaffee’s drawing Impasse, with its dramatic contrast between black and white and its elegant “feathering”, I assumed it was a wood-block print. I was astonished to learn that this is a charcoal drawing, despite the fact that every line looks like it was laid down with a brush and india ink. In this enormous 60” x 70” drawing, I didn’t see a single fingerprint. Its perfection in so visible that it almost feels like a stunt; that it exists for viewers to ask, “How did she do that?”

I was amazed that anyone could produce a huge charcoal drawing with such dark lines and black rectangles crisply drawn against a clean white page, but even though this drawing is an amazing technical feat, I’m most intrigued by the image itself. The dense growth of flowers seems to come from behind a completely abstract pattern of black rectangles, seemingly floating in space. It’s as if the natural world is fighting a war against the world of abstraction, of Platonic ideal forms. The 3D world is arguing with flatness and winning. Chaffee is triumphing in a philosophical battle against an arid visual approach (or perhaps she is expressing an aversion to Raymond Pettibon and Black Flag.)

A lot of Chaffee’s pieces in the show have somewhat abstract titles that begin with the letter “i” like “involute”, “impasse”, or “interlacements.” These titles sound slightly scientific or intellectual, perfect for brainy, difficult artworks. While Chaffee’s artworks invites contemplation on the viewer’s part, they seem as welcoming as a well-tended garden.

One might speculate that over the course of a life together that two artists’ styles might converge, but based on a sample of one, I think that the hypothesis is not proven. Chaffee and Huerta have quite different approaches to producing art. (Huerta and Chaffee do occasionally collaborate, though.)

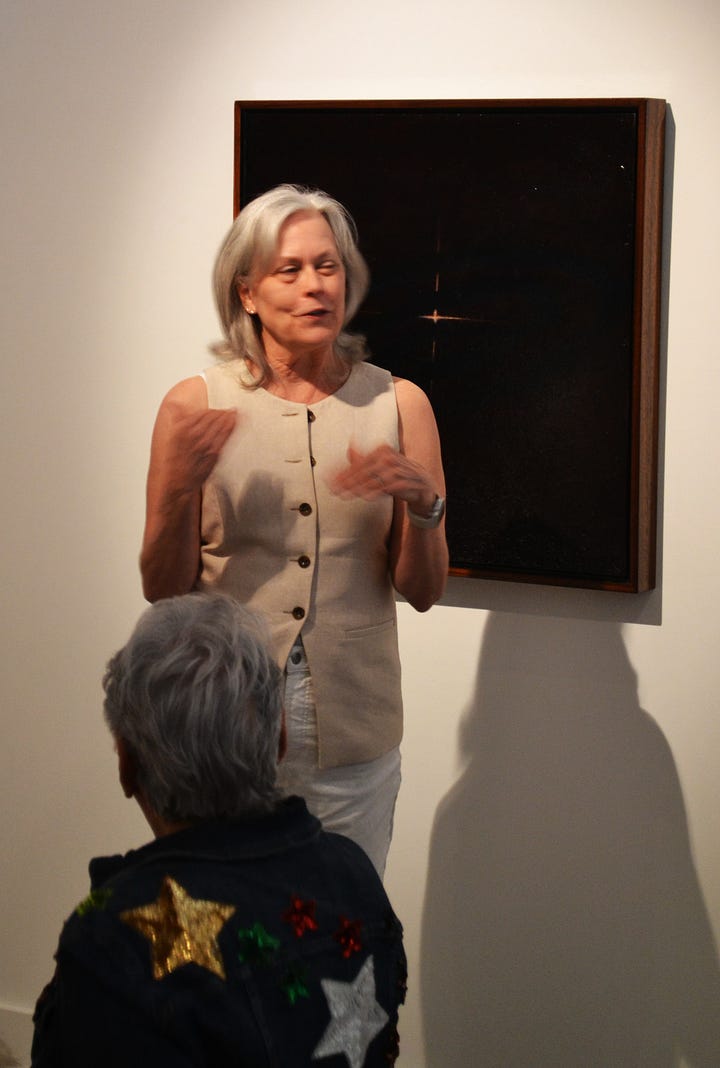

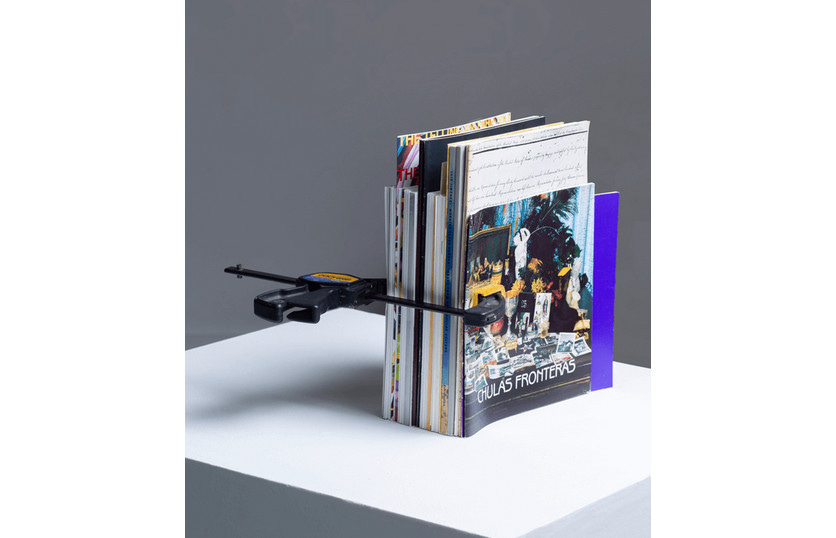

The two artists spoke about their work on the day I visited their exhibit. Huerta spoke of an early group exhibit he was in at the Midtown Art Center that included work by Ibsen Espada, who died recently. According to Huerta’s CV, he participated in two group shows at the Midtown Art Center in the early 80s—the Midtown Arts Center seems to have been a vital part of Houston’s art scene back then. What happened to it? His memories of Espada were a reminder of his intimate connection with Houston’s art history. This exhibit is not about art history, but included was a collection of catalogs from earlier exhibits in which Huerta participated. Huerta has had a major effect on the art history of Houston, and when an artist gets to his 70s, that’s a good time to start reflecting on that legacy.

He Said, She Said is on view at Andrew Durham Gallery through the end of this month.

[Please consider supporting this publication by becoming a patron, and you can also support it by patronizing our online store. And one more way to support this work is to buy books through The Great God Pan is Dead’s bookstore. ]

There’s an edition of Gulf Coast that had a fantastic Barthelme letter to ConEd. If you haven’t read it it’s worth seeking out. I haven’t managed to find it anyplace else.