In the 90s, comics readers like me were becoming aware of how vast our favorite art form was—that for over a hundred years, artists on pretty much every continent had been producing comics or one sort or another. I was talking with Colin Blanchette, creator of the Canon fanzine, the other day about the 100 Best Comics of the Century issue of the Comics Journal—issue 210, published in 1999. We spoke about how that period saw an explosion of critical discussion of all sorts of comics—professional fans like me were becoming very well-educated about this art form. While there had been a few academics working on comics in the 80s and earlier, the number exploded in the 90s, and they all stayed in contact with each other through the internet. These were the days before Facebook, Twitter, or blogs—the way we set up a conversation for multiple people was through an email list. For subscribers of a particular list, every response you make is forwarded to everyone else on the list. I was an eager participant in a list called Comix@. It was in the 90s that we became familiar with manga, with alternative French comics such as those being published by L’Association, with mini-comics and the self-publishing movement. It was the decade when alternative comics festivals like APE and SPX started being important gathering places for enthusiastic amateur comics scholars like me. The participants in these festivals and these email mailing lists were like the inhabitants of a small village full of people insanely knowledgeable about comics. A village like Hicksville, Dylan Horrocks’ antipodean comics paradise.

Horrocks is a cartoonist from New Zealand who was involved in both the Australian and U.K. small press scenes. In the mid-90s, he began publishing a comic called Pickle for a tiny, one-person Canadian publisher. In Pickle, Horrocks serialized a story called “Hicksville” set in a tiny New Zealand beach town inhabited by a people who eat, sleep, and breathe comics. Horrocks wrote a story that required that its readers be well-versed in comics history, perhaps the tiniest potential audience possible. I was an eager member of this inherently tiny cohort. As Pickle was being released, each chapter of “Hicksville” was being dissected by the participants of Comix@.

A couple of weeks ago, I was walking with a friend through the hallways of Winter Street, a home of dozens of artists’ studios, and we noticed that there were a lot of photographs of other people’s art. We looked down our noses at the “Sunday photographer” types that used their art to reflect the glamor of someone else’s art, but later I felt a little guilty over this smug attitude—after all, some of the most meaningful art I know is basically art about other people’s art. Hicksville is an excellent example.

Horrocks is a very self-aware artist. He opens the book with a surreal piece of auto-fiction, a short story not related to the action in the rest of Hickville, called “Augustus E.” Horrocks receives a letter from Augustus E. from a place called Hicksville, N.Z. He evidently knows neither who Augustus E. is, nor of any place called Hicksville. The letter contains a folded piece of paper on which is drawn a page from a comic book. The page depicts a 18th century English sea captain carrying a duffelbag over a landscape and meeting with a Maori man with detailed facial tattoos. A week later, he gets another letter from Augustus E. containing another page from the strange comic. Horrocks is living and working in England in this story, and the mysterious letters seem to be calling him home—both to New Zealand (where Horrocks is from) and to the world of comics. The strange comic will appear as an unexplained McGuffin in Hicksville.

Leonard Batts is a reporter for Comics World Magazine researching a biography of the world’s most popular and successful cartoonist, Dick Burger. Burger is from a town in New Zealand called Hicksville. Comics World is something of a fictional counterpoint to Wizard, a glossy comics fan magazine that was hugely popular during the 90s and 2000s. Leonard (and we readers) know nothing about Hicksville. Leonard is reading a superhero comic book as the chapter opens—-Captain Tomorrow: Rebirth. In it a superman-like figure is battling supervillain named Nullifier. This comic was written and drawn by Dick Burger. The action seamlessly transforms from the Captain Tomorrow comic to Leonard Batts hitchhiking to Hicksville. He’s hitchhiking because Hicksville is apparently so remote that the local bus line doesn’t go all the way there. In what seems a bit of a Hollywood cliche, he is picked up by a beautiful woman in sunglasses and a convertible. She is Grace Pekapeka, and she is surprised to learn that Batts works for a magazine about comics (because it’s a weird job) and concludes he is there to talk to “Kupe”. Batts tells her that he is there to find out about Dick Burger; Grace without explanation stops the car and tells Leonard, ”Get out.”

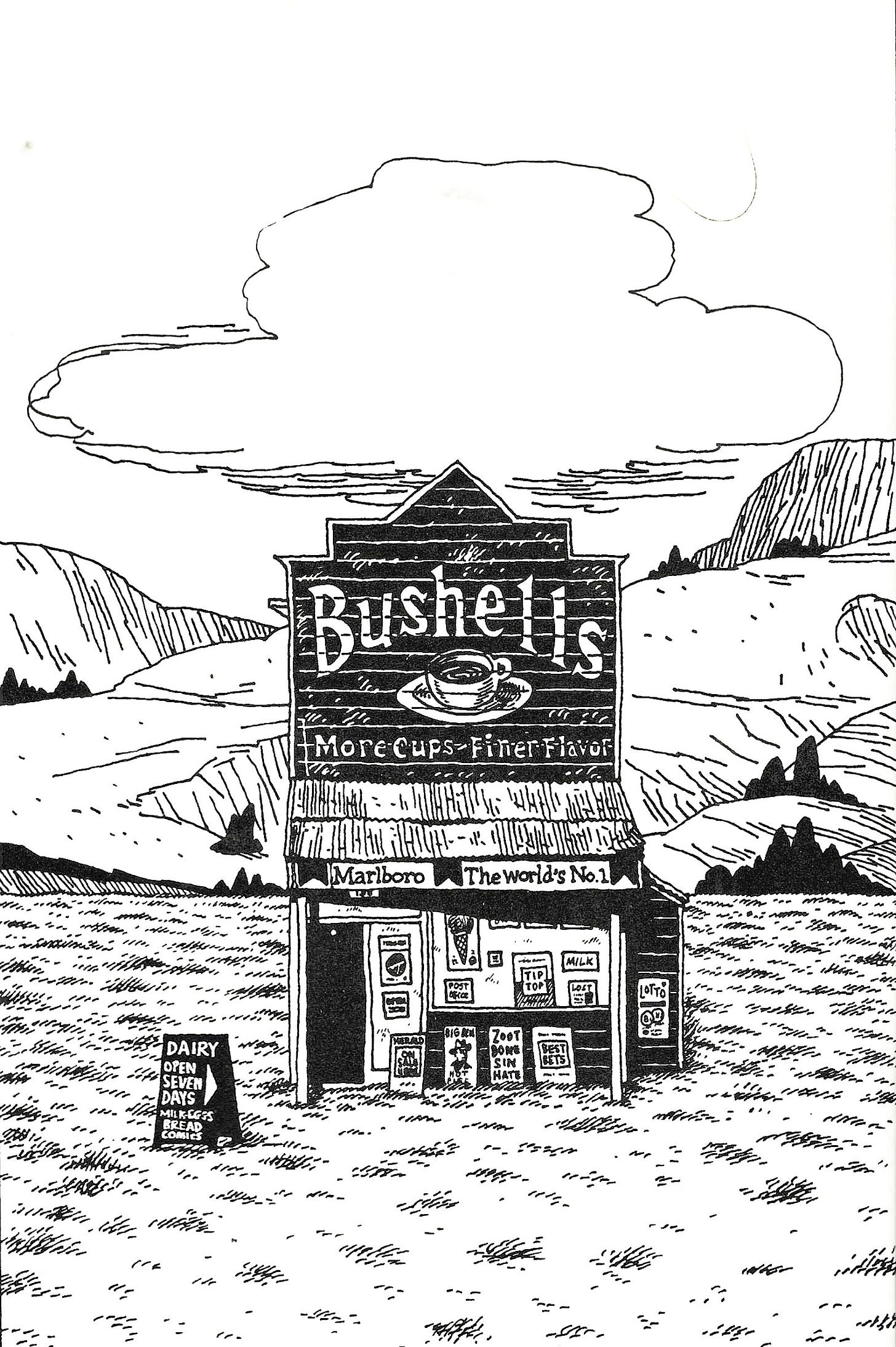

Leonard is stranded in the middle of nowhere, still apparently miles from Hicksville. He starts walking, acquires a map from an isolated shop, and on the back of the map is printed a comics page—the same curious comic about the captain and the Maori man trying to figure out where they are. Leonard, lost, falls asleep in some tall grass where he is rescued by a rustic stroller. He wakes up in a comfy bed in a room full of foreign-language comic books and Winsor McCay prints on the wall. Winsor McCay was the creator of many classic comic strips, including Little Nemo in Slumberland.

He has been taken to a house owned by Mrs. Hicks, proprietor of the Hicksville Bookshop and Lending Library. This is our first hint that the hamlet of Hicksville has an unusual relationship with comics.

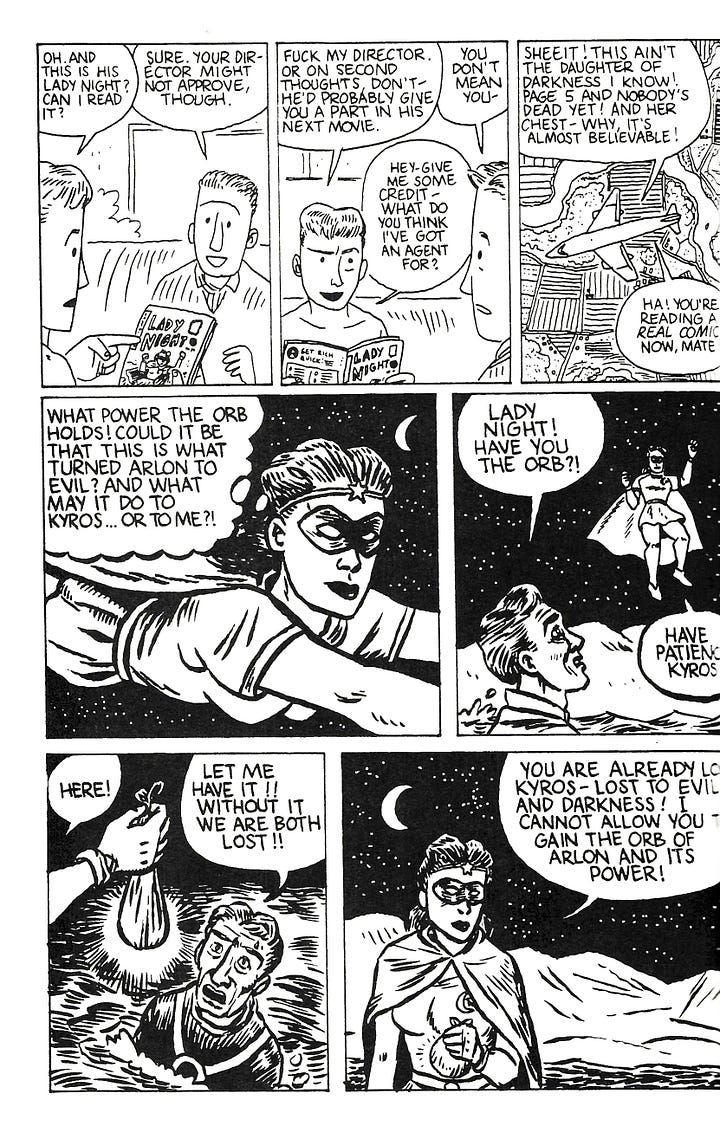

Here we can see characteristics of Horrock’s art. His figures feel cartoonish, but their proportions are basically correct except for somewhat elongated heads. Otherwise his artwork is mostly realistic. Mixing realistic settings with stylized figures is a kind of aesthetic that is common in Japanese comics. Beyond drawing habits, Horrocks is an experimental story-teller. Hicksville is full of comics within comics, giving Hicksville a somewhat postmodernist vibe. And there is something about postmodernism that loves talking about other artworks. Hicksville is a postmodernist tribute to the art of comics just as If On a Winter’s Night a Traveler is a postmodernist tribute to literature.

Mrs. Hicks introduces Leonard to various townspeople at the Rarebit Fiend, a cafe. (The cafe is named after a very early comic strip by Winsor McCay called Dream of the Rarebit Fiend.) He mentions the purpose of his trip, causing alarm amongst the townsfolk. This is a pastiche of the an English satirist Henry Mayo Bateman, whose cartoon series in Punch, “The Man Who . . .”, lampooned social gaffes among the English upper class. Mentioning Dick Burger is as much of a social gaffe as asking for a double scotch in the grand pump-room at Bath.

Hicksville, it turns out, is a legendary refuge for cartoonists. We learn about it from Kupe, the Maori lighthouse keeper who rescues Leonard after he falls into the ocean. For decades, Hicksville has been a kind of artists retreat and residency for frustrated cartoonists from around the world. Here they could produce their masterpieces, but only if they left the artwork here in the library when they were done. About 10 years before the action in this story, a superhero cartoonist named Mort Molson came to Hicksville and drew his magnum opus, Captain Tomorrow: Rebirth. Dick Burger was a teenager in Hicksville who idolized Molson. Burger stole the art, went to America, redrew it in a more modern style, and became a famous comics tycoon.

Dick Burger’s crime wasn’t merely theft of an irreplaceable cultural artifact; it was in violating the “tapu”, which according to the online Maori dictionary, is “a person, place or thing is dedicated to an atua and is thus removed from the sphere of the profane and put into the sphere of the sacred. It is untouchable, no longer to be put to common use.”

The kind of dirty history of comics Kupe describes above was super-fascinating to all of us would-be comics scholars of the 1990s. But with twenty year hindsight, it is hard not to see Kupe as a kind of “magical negro” kind of character—we white people love to have our confusion cleared up by wise dark-skinned helpers. And a big part of the story deals with how the then modern style of mainstream comics, typified by such “extreme” comics as Spawn, Youngblood, and Savage Dragon published by Image Comics, dropped the humanity of earlier superhero comics.

This contrast was contrived and judgmental, but it rang true to us early 2000s comic snobs. The modern “extreme” style, parodied in the Lady Night panels on the left, seems like an artistic and moral mistake in retrospect. But part of the artistic error in Hicksville is to posit that the corny old Mort Molson-style comics were any better. They were rife with racism and sexism and taught a generations of kids that might makes right.

Another aspect of Hicksville that was massively appealing to we Comix@ participants was its valorization of obscure foreign comics. We sought these out. Lat’s work is a good example of the kind of relatively obscure foreign comics that we delighted in discovering. In Hicksville, the foreign master is Emil Kopen, The character of Grace meets him and hears him talking about esthetics. Kopen as a character and artist is humane and decent—the exact opposite of Dick Burger.

Hicksville has many flaws, but it hit me at just the right time. Horrocks had perfectly documented my mindset at that time. Hicksville was seen as a masterpiece when it came out. In retrospect, that was giving it too much credit and looking past certain flaws—the romanticization of the Maori characters, the undeserved nostalgia for bad art of decades past, the superfluous family subplot. But I can forgive us Comix@ types who overpraised Hicksville when it came out because Hicksville was so perfectly made for us.

[Please consider supporting this publication by becoming a patron, and you can also support it by patronizing our online store. And one more way to support this work is to buy books through The Great God Pan is Dead’s bookstore. ]

PS. As a participant in Comix@ and the whole subculture you're talking about, I think this re-view is spot-on, and, as the cliche goes, it really takes me back. Thank you.

(I found in my office just yesterday a print-out of my Comix@ "diary" recounting, in detail, my first ICAF experience in 1996.)

Great re-view, Robert!

One thing I remember enjoying about Hicksville was the parodic invocation of colonialism through telling details like "Captain Cook's Comic Cuts." I do agree, though, that the story too conveniently makes Leonard the ignorant White guy who gets schooled by wise Indigenous people. (The implicit analogy between colonization and the cutthroat business of comics is strained.)

Another thing I enjoyed about Hicksville was its detours into what I'd call autotheory, like the reflections on comics vis-a-vis cartography.

What do you think of Horrocks' later GN, "Sam Zabel and the Magic Pen"? It's politically smarter, in the sense of self-aware and even guiltier than "Hicksville," but I don't know that that makes it an improvement. Beautiful book, though; I have an original page on my wall.