In 1968, Paul R.Ehrlich and Anne Ehrlich published a book called The Population Bomb. The idea was that the human population of Earth was growing to unsustainable levels. The concept was not new, but this book popularized it. In a way, it was a restatement of 18th century British economist Thomas Malthus’s conjecture that human population would always outgrow our ability to produce food, resulting in famine. So far, Malthus has been wrong. Modern famines have mostly been a result of political decisions (Ukraine in the 1930s, Bengal during World War II, Ethiopia in the early 1980s). Technological advances in farming and food production have kept up with human population growth. But the ideas in The Population Bomb, which was followed in 1972 by a similarly pessimistic book called The Limits of Growth from 1972, sunk in and quickly became a part of popular culture.

Science fiction stepped up with numerous novels dealing with the consequences of over-population, most notably, John M. Brunner’s 1968 classic Stand on Zanzibar. (Overpopulation has been a theme in print science fiction since the 1950s—science fiction writers are usually ahead of the general public on issues like this.) It became the subject of many movies of the era, including Soylent Green (1973) and Logan’s Run (1976). These dystopian films suggested upsetting and drastic means for dealing with overpopulation—cannibalism and culling the population, respectively.

These are all narratives that seek to understand the issue in a more-or-less plausible way. But one of my favorite works of art about the basic idea of overpopulation is “People . . . Ya Gotta Love ‘Em” drawn by Robert Crumb in 1989. Here the issue is not the sociological or economic consequences of overpopulation. This story is about Crumb’s own misanthropy.

He depicts himself in an unending scrum of naked people, all involved with their own shit, that he pushes through until he can find peace by soaking in the ocean, which no one else will enter because “The toxic level is up to 43 percent now, ya know!” The Crumb character would rather court death than exist in the crowded, obnoxious civilization in which he finds himself.

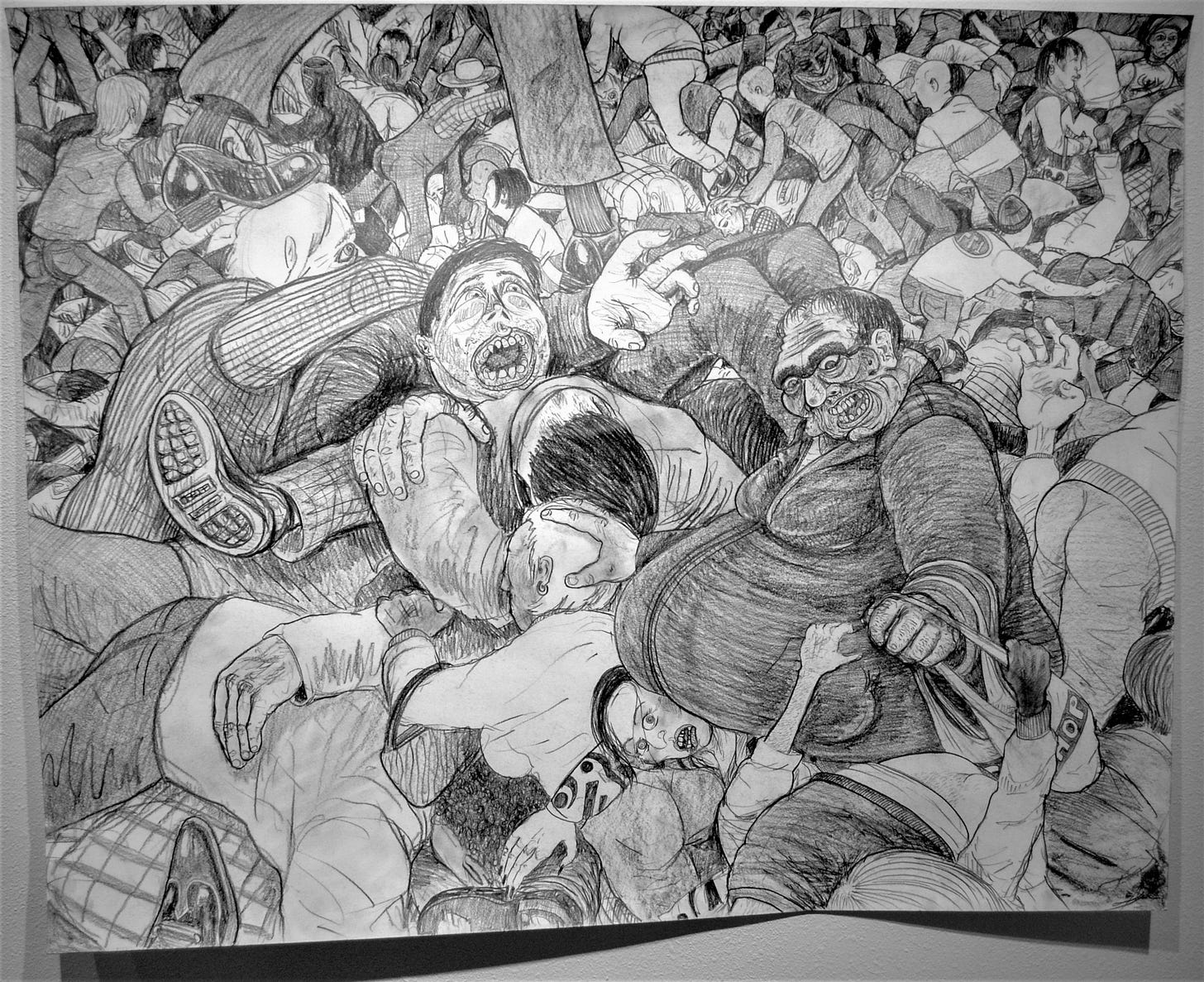

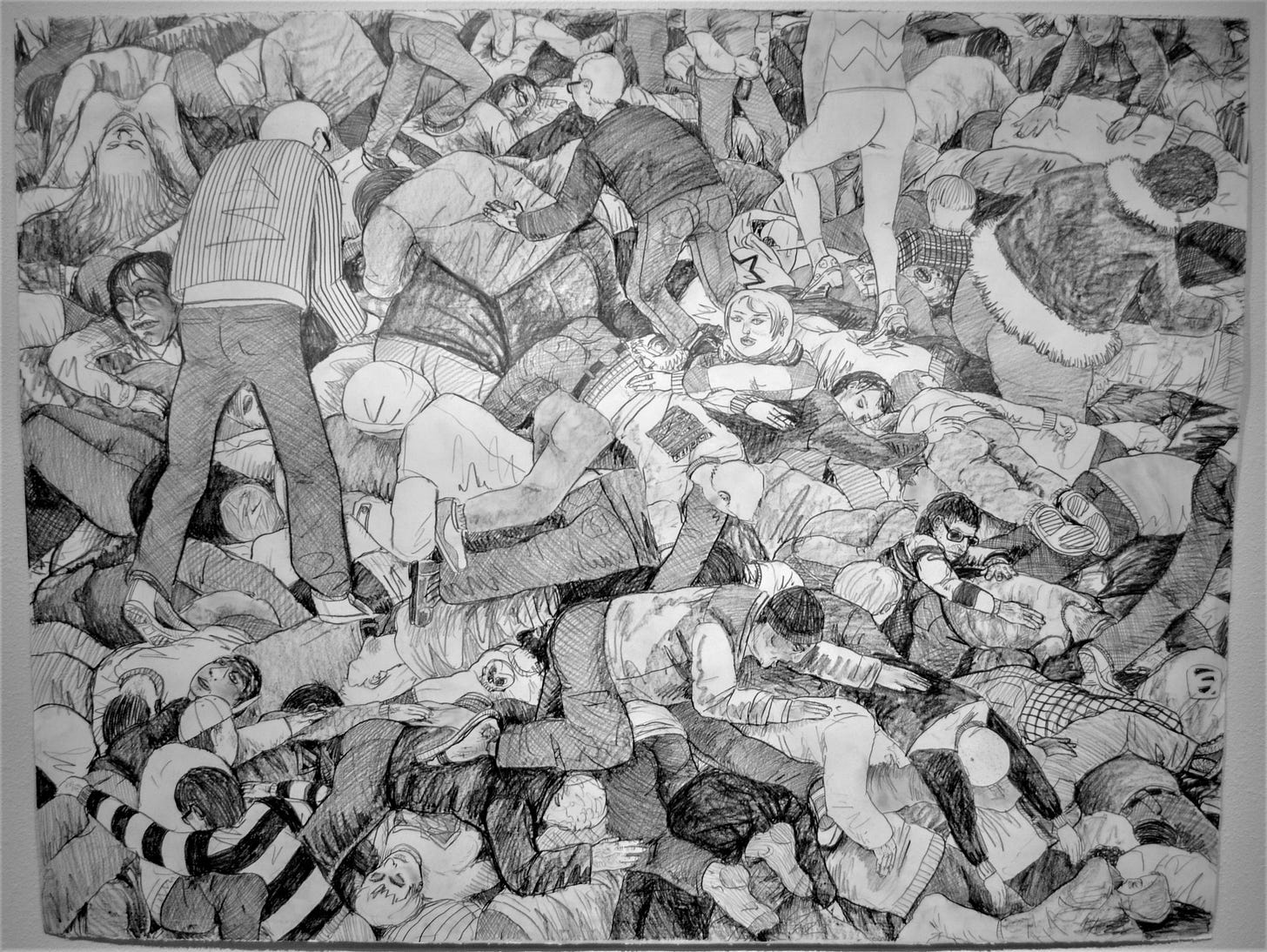

It was Crumb’s story that I was reminded of when I saw Joachim West’s exhibit Critical Mass at the Galveston Arts Center. It is a combination of large-scale drawings and ceramics (!) that play off the basic idea of “too many people”. Like the figures in “People . . . Ya Gotta Love ‘Em”, human bodies are pressed against each other in a gigantic crowd. (West, unlike Crumb, gives them clothes.) And there is a basic feeling in West’s work of disaster and violence. These are people who are trapped in a dangerous crowd, some getting smushed underneath.

Critical Mass makes me think of such infamous crowd disasters as Riverfront Coliseum in 1979 where 11 people were trampled to death trying to get in to see the Who, or more recently, when 10 people were trampled to death at a Travis Scott concert in Houston in 2021. West’s crowds are desperately climbing over one another trying to survive. Some appear to have succumbed. And in desperation, violence has broken out among some who are not yet dead.

In one large drawing, West adds another element—the roiling crowd is loomed over by an enormous bug—sort of like a centipede with a death’s head. It is grabbing bodies off the pile.

While Crumb was showing us his misanthropy, West is terrifying us. The irony of Crumb’s work is missing in Critical Mass: here the subject is terror.

The ceramic vessels in the show are thematically similar. Some of them are decorated with drawings on the sides which appear to be inscribed into a white glaze, so they are black and white line drawings.

But most interesting to me are vessels where the bodies are sculpted as relief figures. In these the figures are mostly laying face down, as if they have already been trampled to death.

But in one, a seemingly distraught woman in kneeling on the fallen body of a man.

It reminded me of the famous 1970 news photo taken at Kent State in which Mary Ann Vecchio kneels over the dead body of Jeff Miller, who had just been murdered by the National Guard. In West’s ceramic, the woman is on top of the body (which Vecchio was not) and her arms are grasping something in front of her, not raised like Vacchio’s were. Actually, the two images are quite different. I think the reason one made me think of the other was the feeling they both evoke: dread.

West is pretty well known for his disturbing imagery of decaying, horrific urban scenes, but this show has some of his most disturbing work. Instead of drawing horribly distorted urban mutants, as he has done in the past, here he drew ordinary people in a terrifying situation of being trapped and crushed in a chaotic crowd.

Critical Mass is up until May 29.

[Please consider supporting my work by becoming a patron, and you can also support my work by patronizing my online store. And one more way to support what I do here is to buy books through my bookstore. ]

So good to see this artist! Thank you, Robert.

Love this, Robert. So glad you wrote about West.