I am a collector of original comic artwork—old comic strips and comic book pages. One of the pleasures of this hobby is that you get to see how much more stuff is on the actual pages that artists drew than is on the printed pages. For instance, one often sees the underdrawing in the originals—it is usually drawn in faint blue pencil. Or one sees the whiteout the artist used to correct mistakes. Or marginal notes to the editor or letterer. All this stuff is erased in the production and printing processes. Original art has a kind of auratic feel (in the Walter Benjamin sense). I have curated comic art exhibits full of original artwork because I totally respond to the seeming magic of a piece of art that was physically touched by the artist. But seeing comic art displayed on a wall feels off to me. The actual finished artwork is the printed comic—whether in a newspaper, magazine or book. There is an analogy with film—if we want to experience the art of, say, Yasujirō Ozu, we watch Tokyo Story—we don’t look at the actual 35mm film he took.

Because there is a sometimes dramatic difference between the printed work and the original art, it has become a fad in the past decade to publish editions of classic comics that reproduce what the art looked like—so all the blue lines and whiteout and marginal notes to the editor are there to see. It puts the reader a little closer to the artist. We receive insights about the artistic process. It is from looking at Jack Kirby’s original art that we learn that he, not Stan Lee, wrote his own comics. I want to use a book of such exact reproductions to talk about one of my favorite artists, Jerry Moriarty. The book, Jack Survives (published by an amazing but short-lived art comics publisher, Buenaventura Press), is unfortunately out of print, but a quick look on eBay shows that one can still buy it for non-outrageous prices.

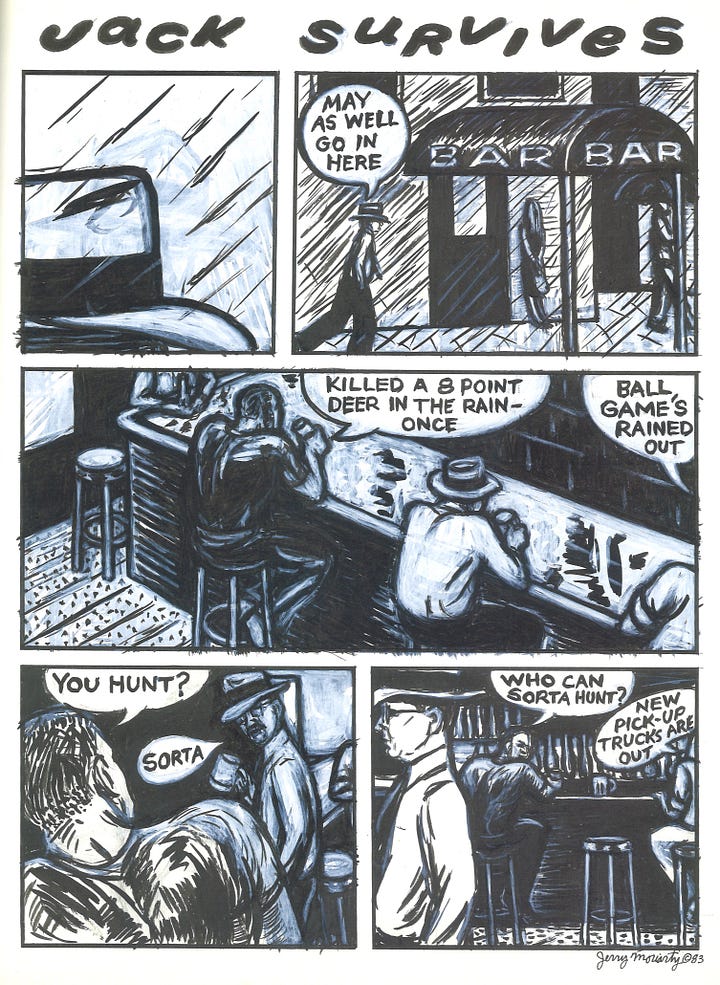

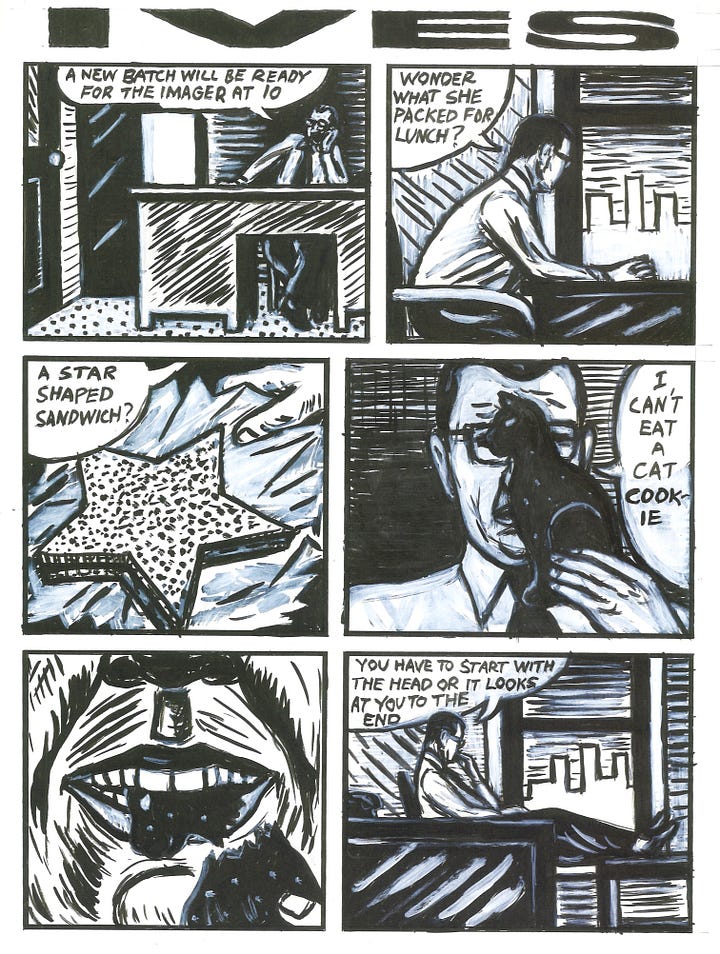

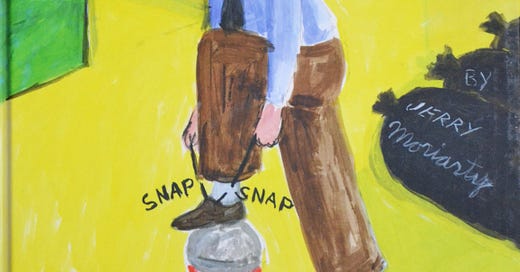

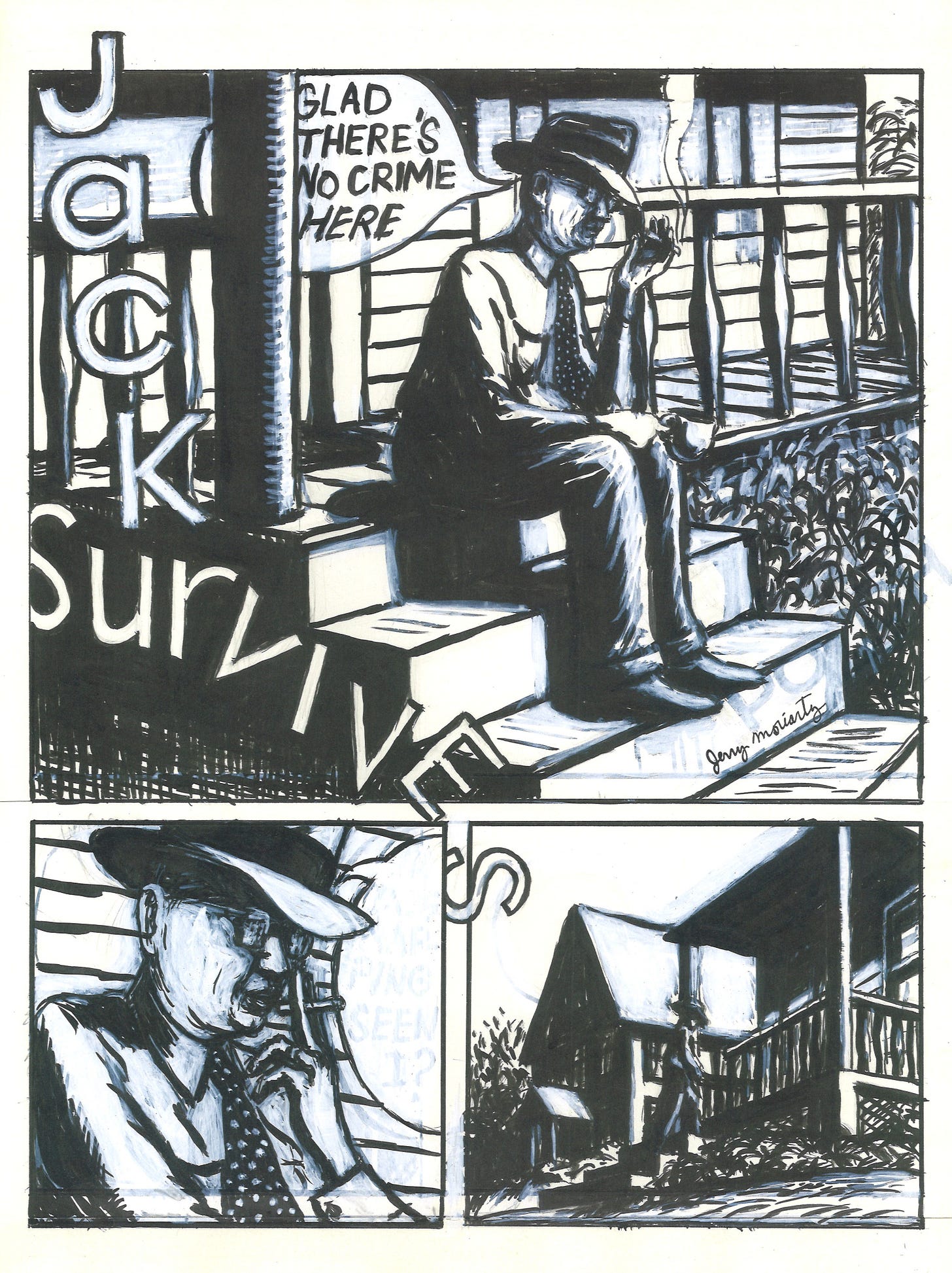

I first encountered Moriarty’s work in Raw, Art Spiegelman’s influential art comics anthology published in the 80s and 90s. Spiegelman brought a fine arts aesthetic to comics that it had mostly lacked until then. The artists he chose to populate Raw were some of the most sophisticated European cartoonists, a few refugees from the world of underground comics, some hyper-talented kids who were among his students at the School of Visual Arts, and a fellow faculty member, painter Jerry Moriarty. The pages that Moriarty drew for Raw featured a stereotypical 1950s man, invariably wearing a wide-brim hat, a white dress shirt and dark slacks. He is usually wearing a tie, but occasionally Jack goes wild and eschews it. He is a suburban blank slate who doesn’t quite fit into the world, but seems to have an ambition: to be a normal, unobtrusive guy.

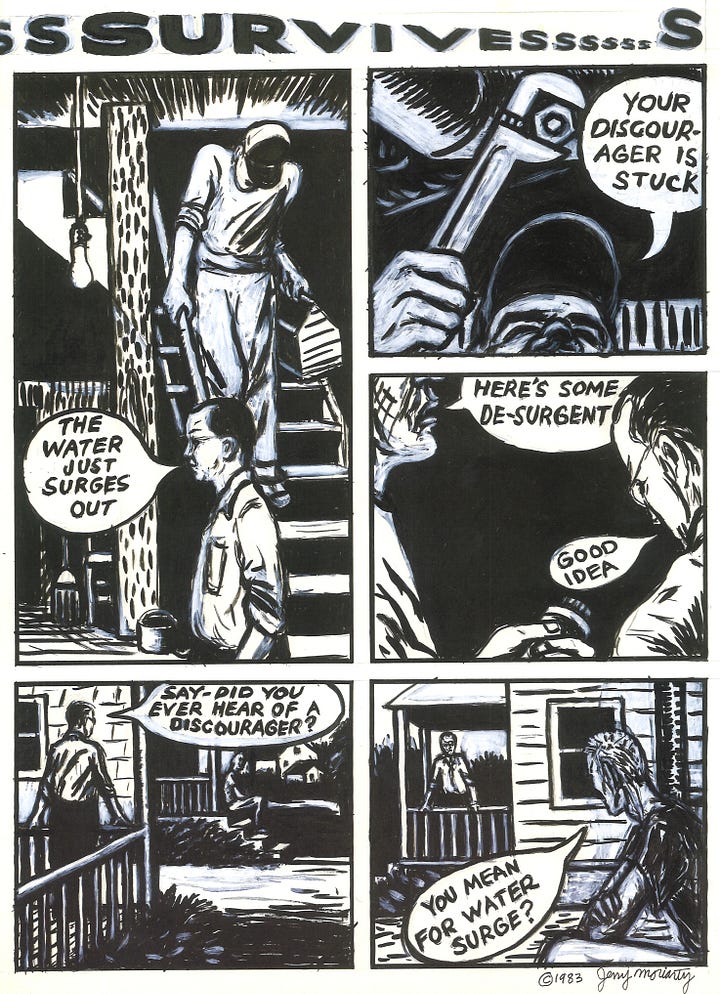

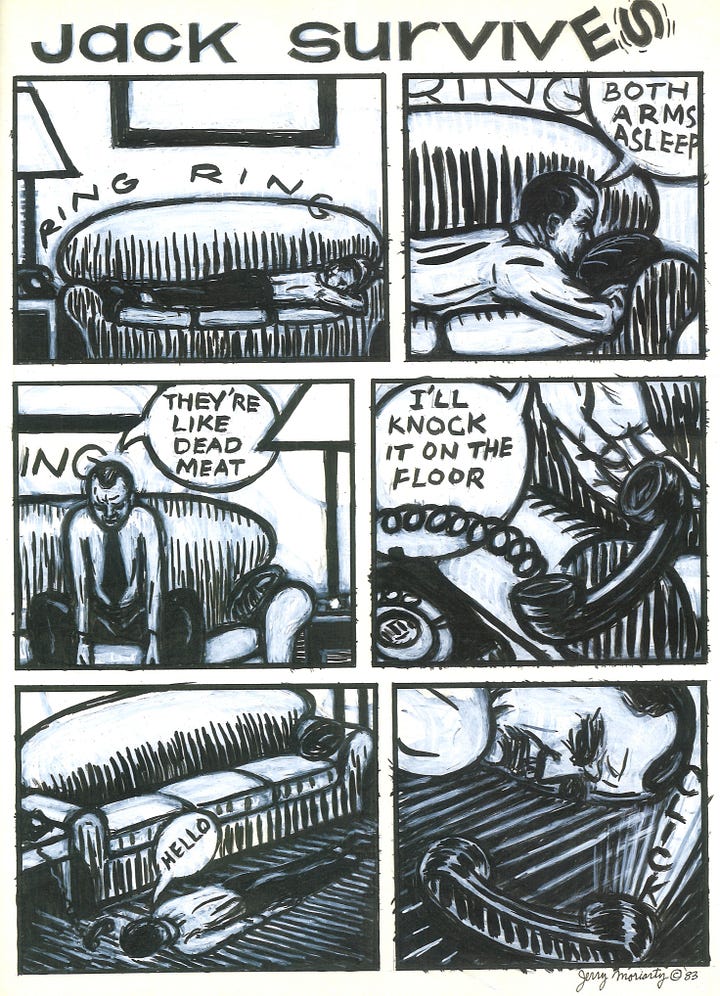

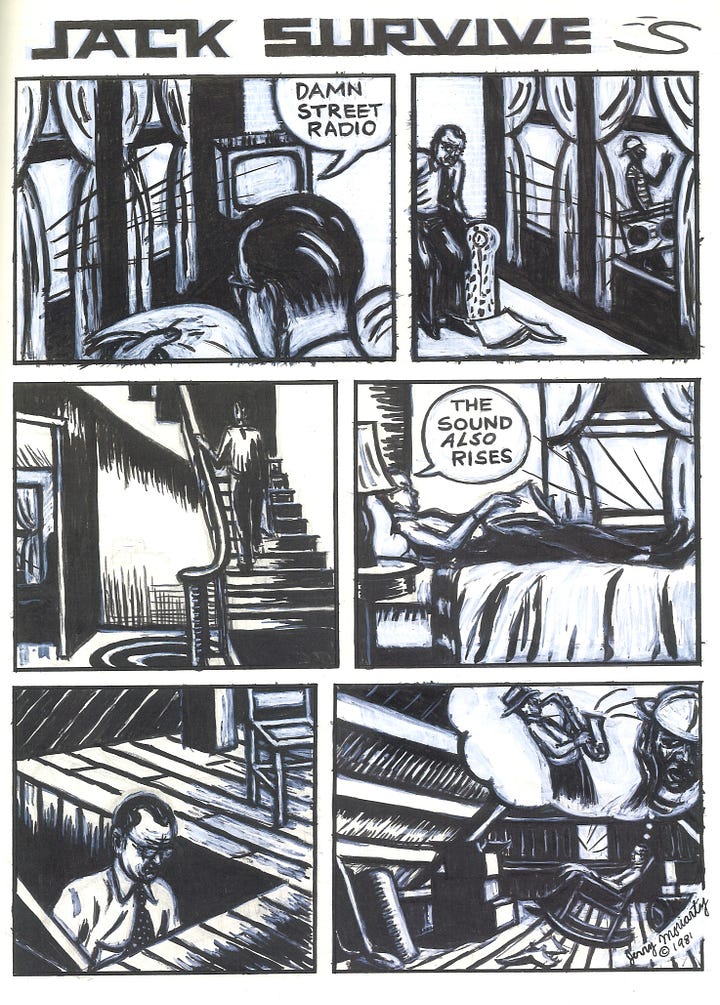

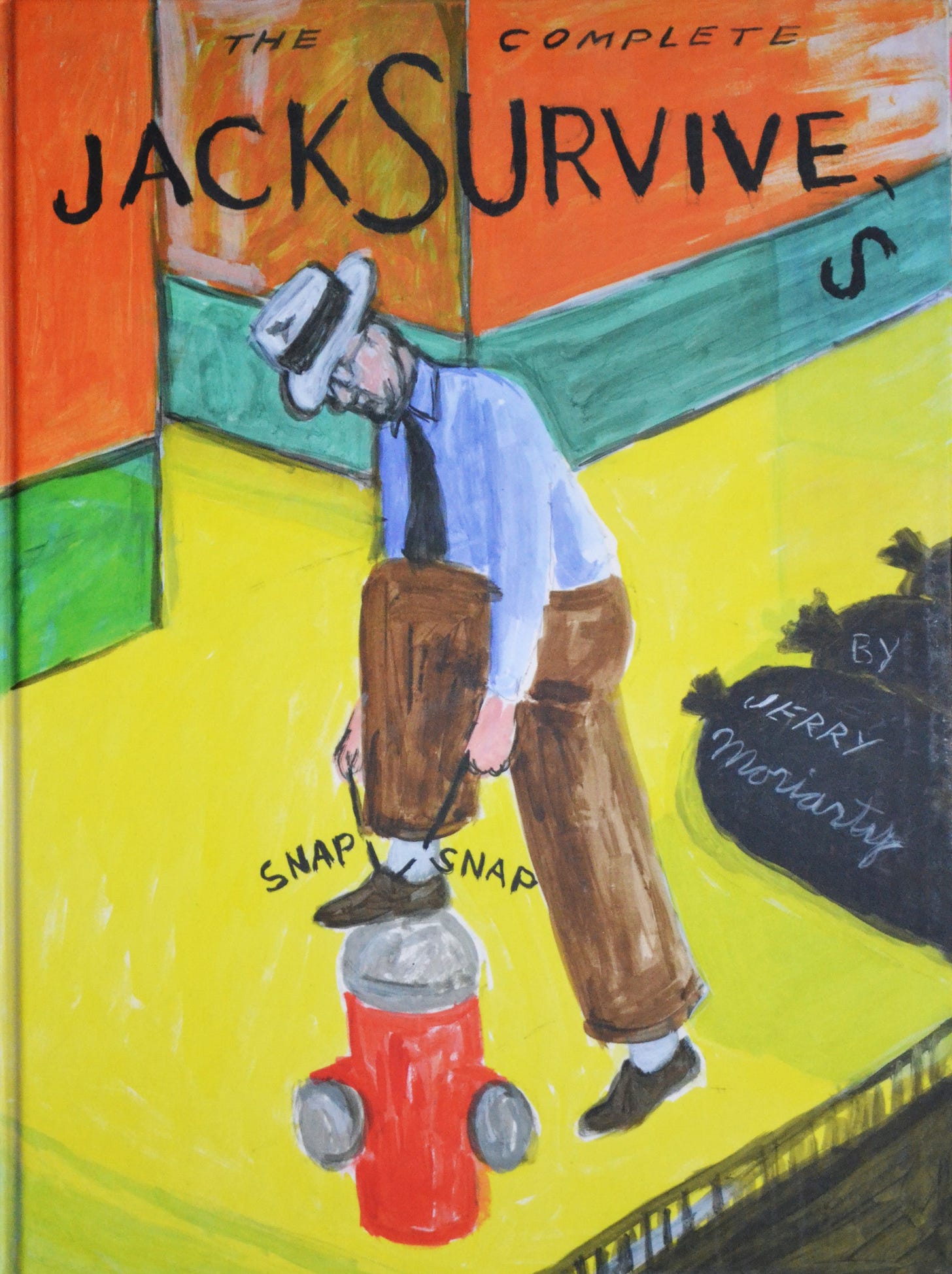

Moriarty is a painter, and all his Jack Survives strips are painted. When they ran in Raw, they were printed with high contrast between the black and white. You could still tell they were painted, but the didn’t appear painterly. It is fascinating to see these not as high contrast graphics, but as painted images, where you can see where Moriarty repainted some panels from scratch as he worked on a given page. In the Buenaventura edition, we see how much labor goes into each page.

The image on the left was taken from my copy of Raw number 6, and the left is from the Buenaventura edition of Jack Survives. The Raw version is full of crisp chiaroscuro, while on right, we can see where Moriarty painted areas with white paint that is not totally opaque. It appears that he completely repainted the second panel. We have to ask if either of these printed versions of the same comic is the authentic, authorized version. This is a weird thing to be unsure of—I suppose we could ask Moriarty himself. He was born in 1938, but he’s still alive.

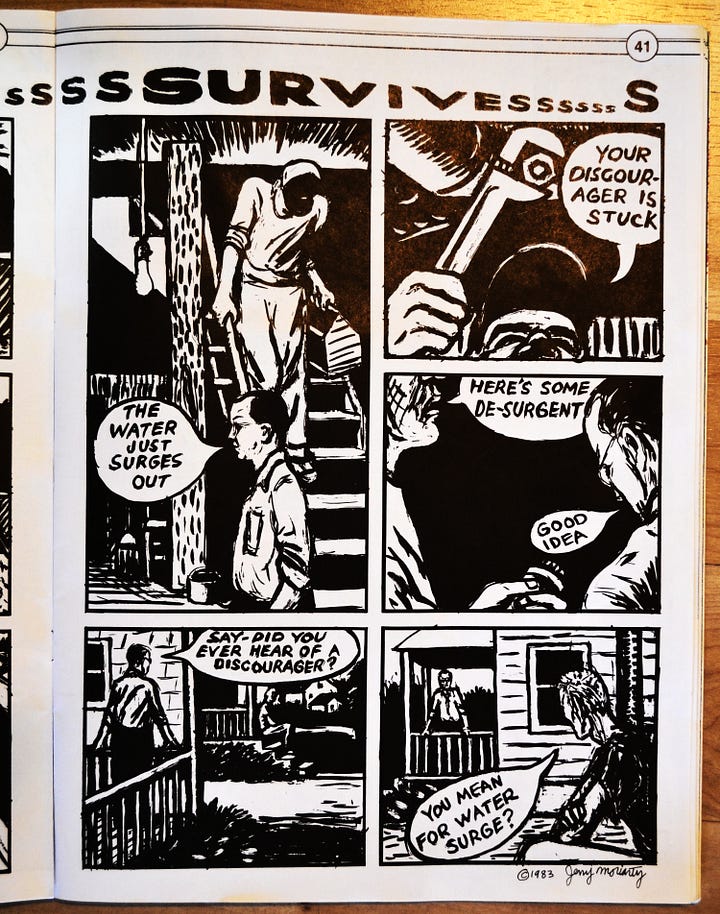

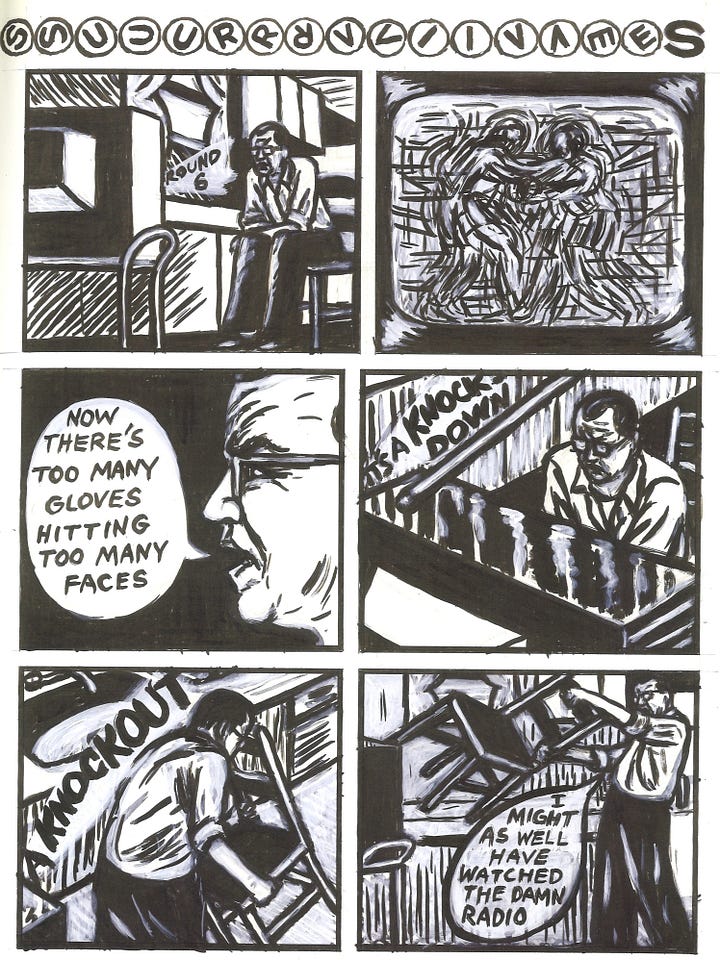

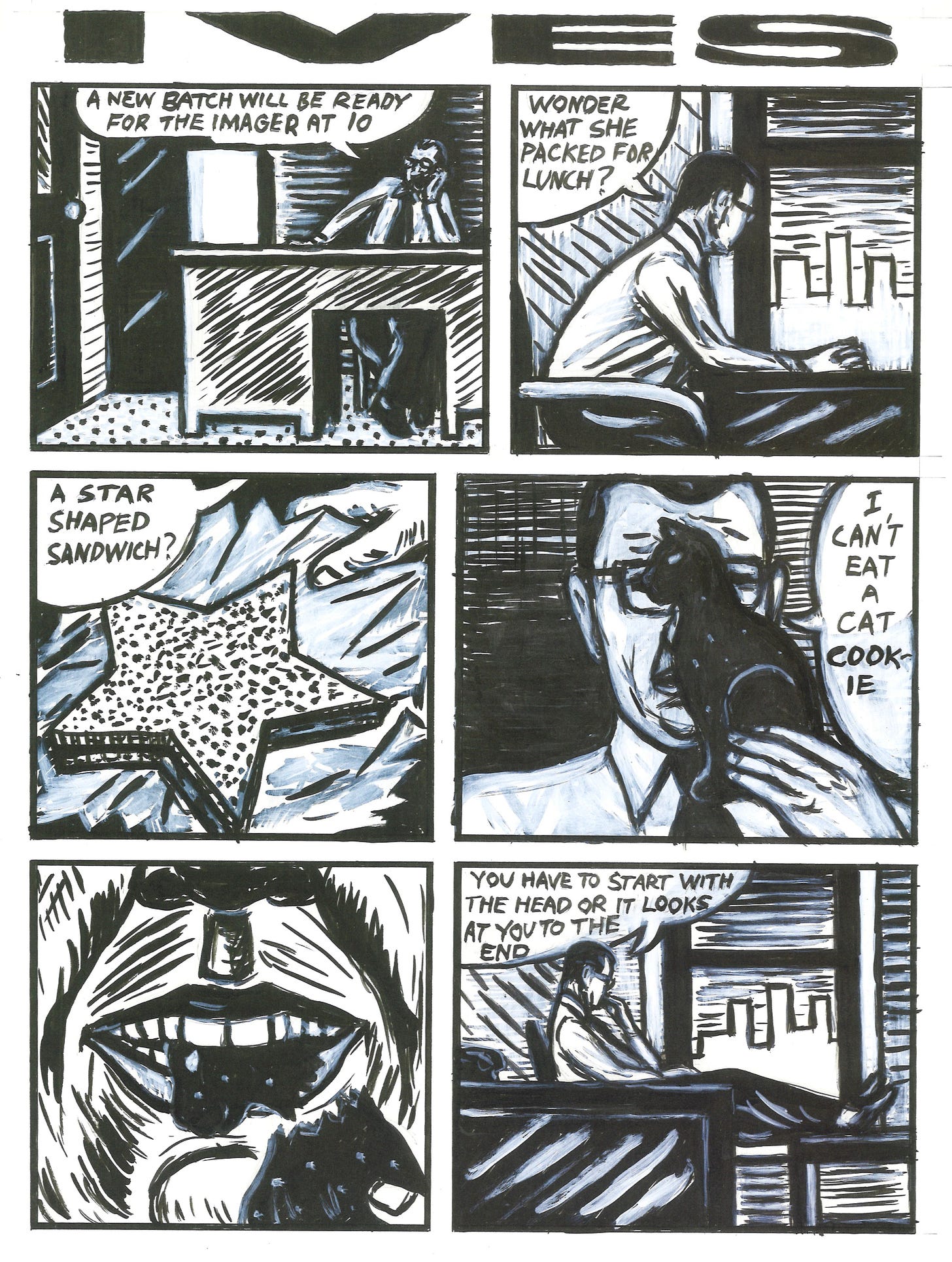

The page above is part of a two page strip. All of the Jack Survives strips are either one page or two pages long. Jack is not a character with a biography—he is more of an embodiment of an attitude. This is the attitude of a kind of slightly insecure, even defensive, but also somehow entitled 1950s men. The strip above is a great example—when the plumber uses unfamiliar jargon, Jack pretends to understand, seemingly so he will not lose face in front of the hired help. To admit that he has no idea what a “discourager” is or what “de-surgent” does would show weakness before a lower status male. But Jack is comfortable asking his neighbor what a “discourager” is because his neighbor is of equal status to Jack.

Moriarty writes that Jack is a combination of his own dad and himself. Visually, Jack is designed to look like Moriarty’s father at the time of his death in 1953. Jack is a somewhat solitary man—which Moriarty describes as being more like himself than his gregarious father. Outside the strips themselves, perhaps the best description of Jack is one that Moriarty provides, “Jack is an average man wanting to be average.”

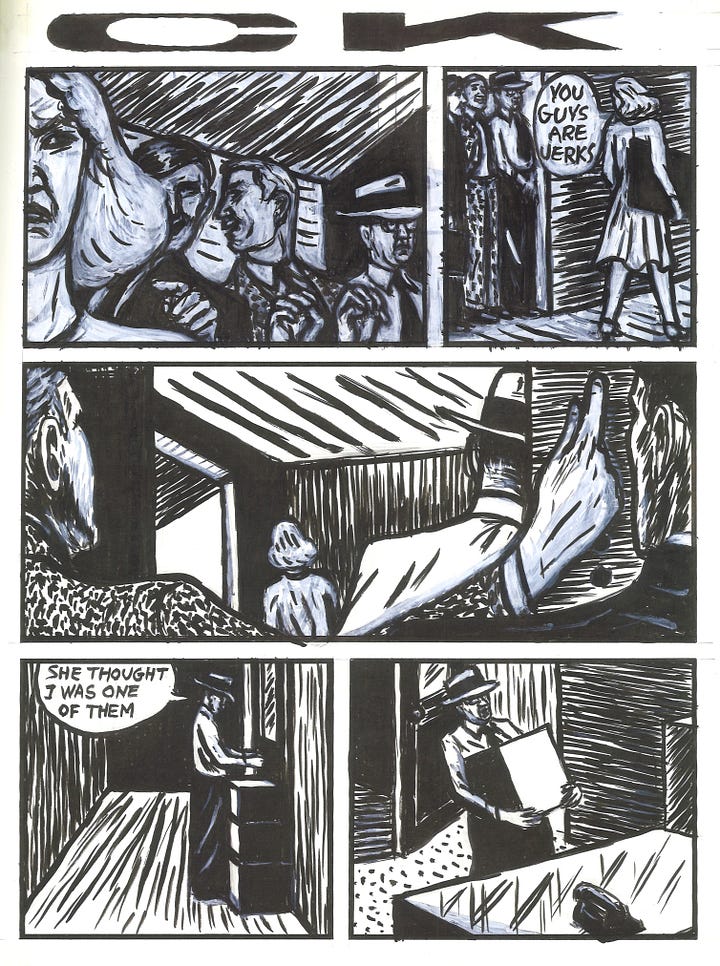

Jack verbalizes his thoughts, as opposed to them appearing as thought balloons. In a way, this suggests that Jack has no inner life, but I think his inner life—his thoughts and daydreams—are his outer life. He has virtually no interaction with other people, and when he does, it’s all business. And encounters with other people lead to Jack feeling uncomfortable in his own skin.

Because Moriarty is painting his strips with somewhat thick goo (it looks like acrylic gouache to me, but I really have no idea), the lines are thick and somewhat crude. And there is no grey paint. Even though we can see areas where the white paint is not opaque, Moriarty never mixes the black and white paint. With Jack saying his thoughts aloud and the crude drawing, Jack Survives is dumb art.

Some art is dumb because the artists are not terribly sophisticated or skilled. But some is intentionally dumb. There are artists who despite their own awesome level of talent and education, choose to make art that is simple. In the fine art world, one thinks of painters like Neil Jenney, William Copley, and the other artists from Marcia Tucker’s influential exhibit at the New Museum called “Bad” Painting. This exhibit was in 1978, so Moriarty possibly saw it. In any case, “bad painting” was in the air. It makes sense that a painter at NYU might see that crude figuration was becoming a popular subject after decades of abstraction and pop art, and might therefore be inspired by it to throw Jack’s hat into the ring.

Moriarty evidently stopped drawing Jack Survives strips in 1984. He mentions his mother Esther in the book, and 25 years after he stopped drawing strips about Jack, he decided to add a new character. After we’ve seen a bunch of strips where a seemingly lonely everyman talks to himself about the trivia of his daily life, he finally gets to have a friendly conversation with another person. Given that Moriarty’s father died in 1953, and Esther lived for another 39 years, it must have been especially satisfying for Moriarty to reunite them in Jack Survives.

[Please consider supporting this publication by becoming a patron, and you can also support it by patronizing our online store. And one more way to support this work is to buy books through The Great God Pan is Dead’s bookstore. ]

Such great drawing.

Love Jack Survives. I’m also a mark for Artist Edition type books, although Jack Survives predates the current obsession with those (as does another great example, the McSweeney’s published Binky Brown).