Before the 1970s, comics in the U.S.A. were physically delivered by wholesale distributors to newsstands, convenience stores, and groceries along with other magazines. Unsold merchandise could be returned to the wholesaler for credit. Unsold magazines had little resale value—they were mostly pulped when they were returned. This was a good system for shop keepers, obviously—it reduced their risk and made them willing to take a chance on new publications. However, it made entering the publishing business very risky. By the 70s, there were two big comic book publishers in the USA—Marvel and DC. In the 60s, underground publishing became a thing, and comics followed suit. Tiny comics publishers in San Francisco and Milwaukee developed their own distribution network, selling comics mainly to head shops. A few specialty comic book stores opened up in Canada and the US starting in the 60s. In the early 70s, some specialty distributors started selling comics on a non-returnable basis. As comic books became a collectible good (as opposed to what they had been—perishable goods), the number of comic book specialty stores increased, and the new distributors scrambled for product to sell to the somewhat new retail category: comic shops.

This feels like a minor change in how the business was organized. But it had an unexpected effect of encouraging the establishment of a plethora of new publishers. Some tried to imitate Marvel and DC to an extent (producing full-color super-hero comic books), but others were more eccentric outgrowths of the underground comics movement of the 1960s. These comics were very cheaply produced in black and white editions. This period is known among hardcore comic book fans as the black and white boom. (Comics fans were not very clever when it came to names of eras.) The most famous comic to appear during the black and white boom was Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles.

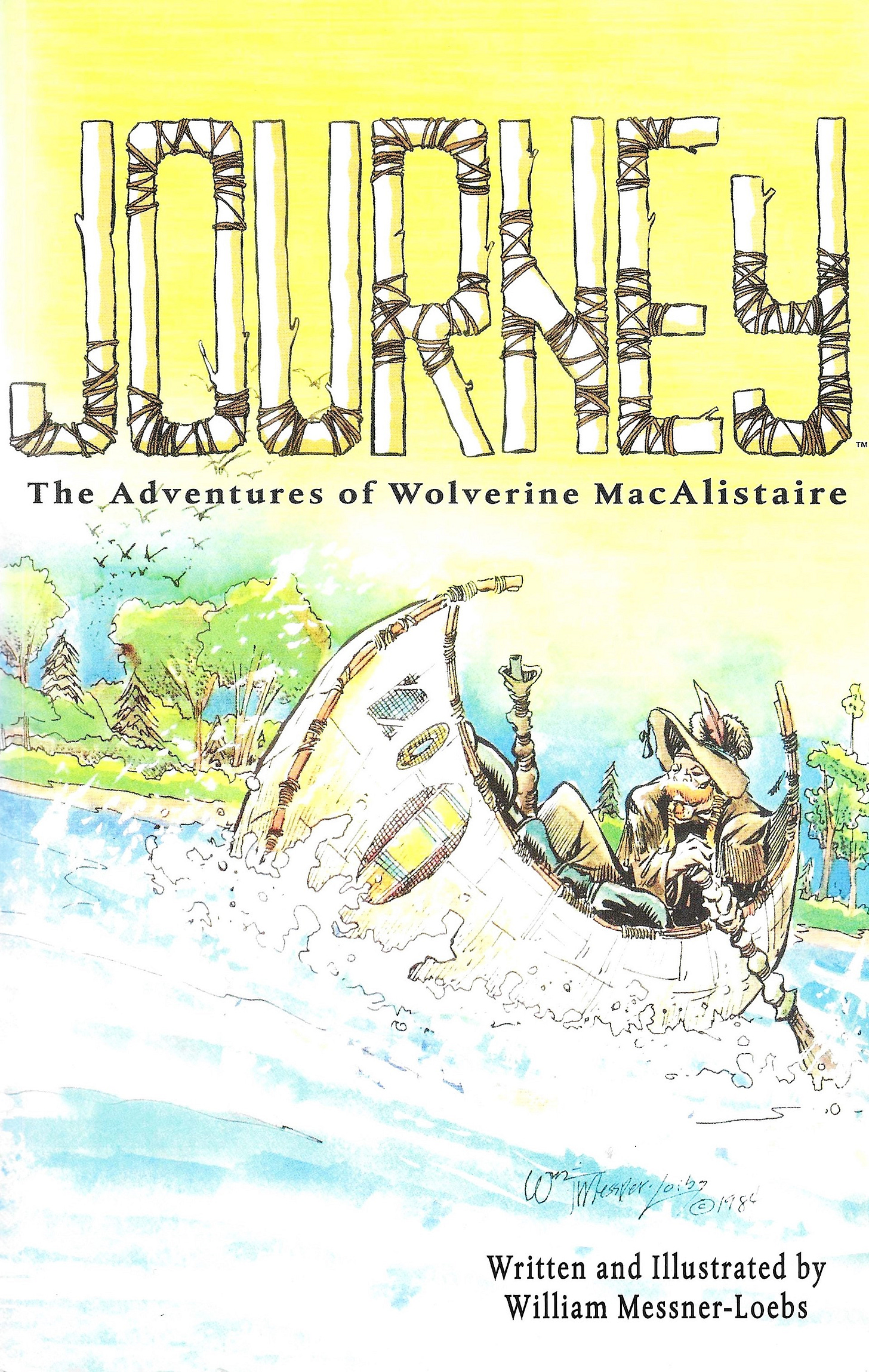

One of the black-and-white boom publishers was Aardvark-Vanaheim which became Renegade after the publishers divorced. They published a line of disparate oddball comics titles, one of which was Journey written and drawn by William Messner-Loebs. Journey was a historical adventure comic set in the American frontier in the early 19th century. The main character is a trapper named Joshua "Wolverine" MacAlistaire, a solo woodsman. American popular culture has long loved tales of frontier life, but usually chose to set them in the old west, with cowboys as the stoic heroes. But Journey demonstrates that the dominance of the old west in 20th century pop culture was a historical accident. The adventures of trappers in the upper Midwest, it seems to me, would have been just as compelling as stories of cowboys, cattle drives, covered wagons, etc. But the age of cowboys in popular culture coincided with the USA becoming an industrial powerhouse, whose tools of mass production also produced mass popular entertainment. If the industrial revolution had arrived 50 years earlier, characters like Wolverine MacAlistaire would be just as popular as Wyatt Earp or Rooster Cogburn. The buckskin fringe could have been just as iconic a pop culture signifier as the six-shooter.

But in an age before mass media, the trappers of the upper midwest never got mythologized as much as the cowboy. Most of the action in Journey is set near Fort Miami, a British fort near what is now the border between Ohio and Michigan. The time is early in the 19th century. At the time of Journey, this territory near Detroit wasn’t clearly the property of Britain, the U.S.A. or of various tribal nations. The politics of Britain and the early American republic touch on the action here, but the politics of Indian tribes in the area are foregrounded.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Great God Pan Is Dead to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.