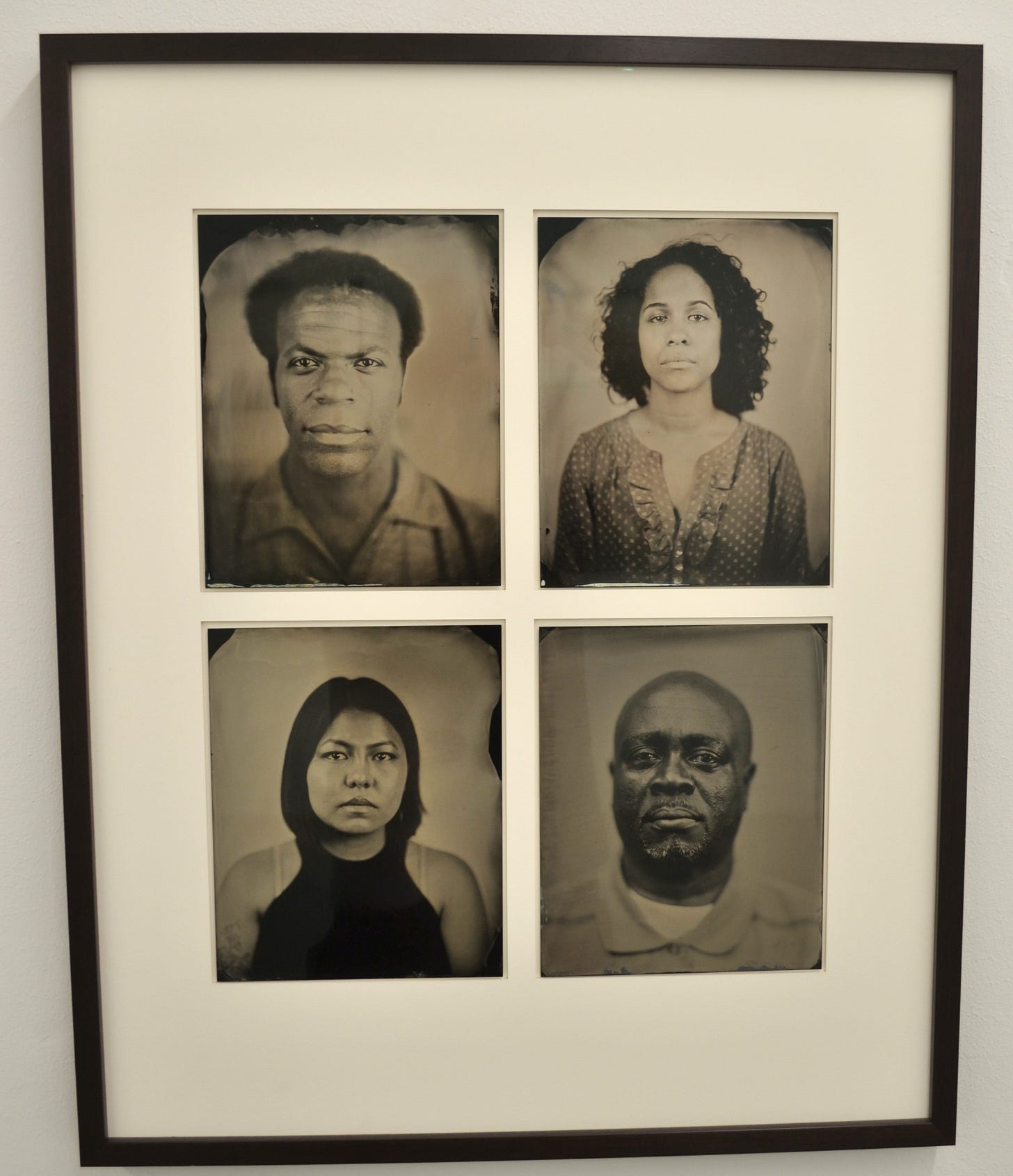

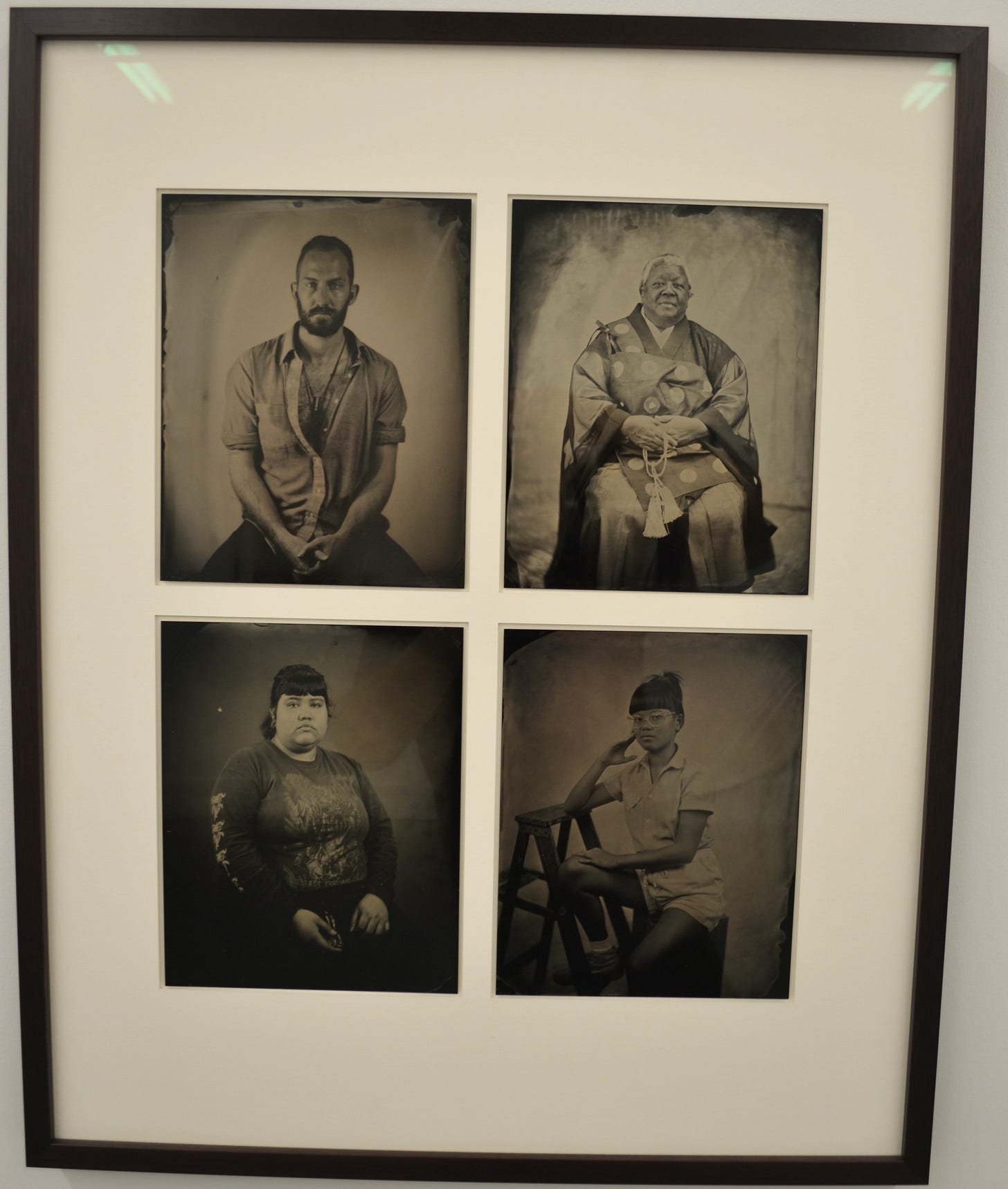

Tintype photos are an obsolete form of photography. The technology’s heyday was in the 19th century and tintypes apparently died out as a common photographic practice in the USA in the 1930s. A tintype was a direct positive image on a thin piece of coated metal. Because this type of photography was obviated by technological improvements, nearly everyone who had their portrait taken on a tintype is dead now.

But old technologies of art-making never completely die. Sculptors still employ bronze foundries, five thousand years after the invention of bronze. Tintypes, especially tintype portraits, have a special quality that other forms of photography don’t have. The images are black-and-white, but the flesh of the subject of a tintype photo seems to radiate somehow. The highlights on a sitter’s skin feel as if they are floating slightly above the picture plane.

Keliy Anderson-Staley is a Houston photographer who specializes in tintype portraits (but not exclusively portraits, as you can see from her website). When I look at a photo like Taylor, I see a young woman in centemporary dress posing in a time machine that has sent her back over a hundred years. The contrast of antique and contemporary is thrilling.

A community of any size needs portrait makers, obviously. While most are performing a service (photographing students for a High School yearbook, for example), at least some of producing portraits as artworks, as Anderson-Staley does. She doesn’t have an obvious mission—her subjects appear to be random people. I don’t know where they are from or what their stories are. Anderson-Staley keeps the anonymity of her subjects by only identifying them by their first names.

This small exhibit entitled One Wild and Precious Life is on view at Basket Books & Art. They are modern faces depicted by a charmingly old-timey means. Tintype gives her subjects an unexpected intensity. It makes her subjects seem as if they are all thinking, “What are you looking at, stranger?”

Weirdly enough, Anderson-Staley is not the only artist in Houston with a practice of producing modern portraits employing an ancient, deliberately old-fashioned technique. Nestor Topchy has produced a huge series of portraits in the form of Eastern Orthodox icons, with egg tempera and foil leaf. When one sees a modern person painted as if Andrei Rublev had done it in the 15th century, the sense of dislocation is powerful. One gets a similar feeling looking at Anderson-Staley’s tintypes. That dislocation makes these modest portraits of ordinary people feel epic.

[Please consider supporting this publication by becoming a patron, and you can also support it by patronizing our online store. And one more way to support this work is to buy books through The Great God Pan is Dead’s bookstore. ]

These are amazing!

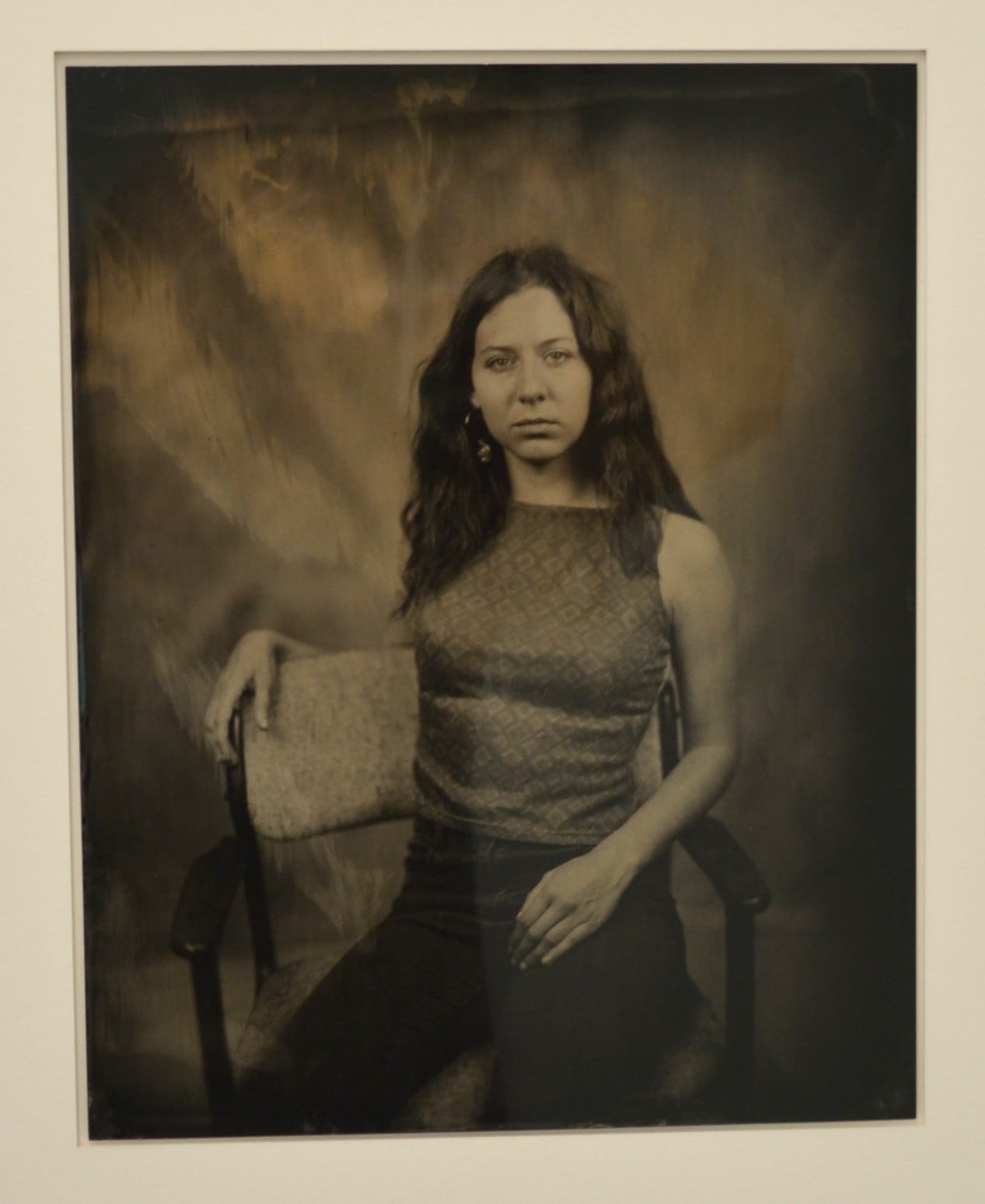

Around 2014-15, Brooklyn artist Galina Kurlat was in Houston. While there she took portraits using the wet colloidal process. I commissioned three poses from her which I find really cool. It was fun to go into her dark room and watch the images appear on the glass as if my magic.