“The past sure is tense”—Captain Beefheart

In the 14th century, the Turco-Mongolian conqueror Timur (1336-1405, AKA Timur Lang AKA Tamerlane) killed approximately 17 million people—about 5% of the total world population. What can a super-villain who died nearly 600 years before I was born possibly mean to me? I grew up in an upper-middle class American neighborhood on a street named for a Confederate general. Several of the streets nearby had Confederate nostalgia names like Plantation, Rhett, and Tara (obviously named by a fan of Gone With the Wind). Several nearby streets were named after operas, like Boheme. About two blocks from where I grew up is a street called Tamerlaine. A 1950s Houston home-builder thought it would be charming to name a street in his new subdivision after a man known for constructing pyramids from the skulls of his victims. As a kid, I had a vague idea that “Tamerlaine” was a person from history. I now understand that he was one of the worst people in history.

I’ve spent the last few years in a highly undisciplined study of history. I have no idea at any moment what event will send me scrambling down a historical rabbit hole. As I read Simon Montefiore’s The World, I would find myself growing positively angry at the Mongols, 800 years after they scourged the Earth. I’m not completely sure why they should make me angry in 2024. They fascinate and frighten me, perhaps in the same way true crime and serial killers fascinate and frighten.

Amongst genocidal super-villains, Timur seems very consequential but not very well-known. Either he is well-known (and my lack of familiarity is a personal failing) or he wasn’t that consequential. I’m going to go with the not very consequential, which is admittedly a weird thing to state about someone who murdered 5% of the world. I’ll expand on this later.

Timur was the last major nomadic conqueror. English playwright Christopher Marlowe wrote a two-part play about Timur called Tamburlaine 180 years after Timur’s death. Handel and Vivaldi both wrote baroque operas about Timur. Edgar Allen Poe wrote a poem about the conqueror in 1827. This is what I mean by “rabbit hole”—thinking about Timur leads me to the Elizabethan theater of Christopher Marlowe and the classical Arabic scholarship of Ibn Khaldun and one of Timur’s earliest biographers, Ibn Arabshah. Timur seems to have fascinated both European and Islamic scholars alike for several centuries after his death. But that fascination seems to have fallen off once Poe wrote about him. I glimpsed at IMDB to see if there are movies about him—the only bioflick I could find was from Uzbekistan. (I also found a webcomic called Tamberlane; it takes place in a magical forest and stars talking animals.)

Timur was born in Transoxania (roughly where Uzbekistan is today) in what might be called the middle of nowhere. Nearby Samarkand would become the capital of his empire. He was born in the ruins of the Mongol empire—his home was in one of the Mongol successor states, the Chagatai empire. (Chagatai was one of Genghis Khan’s sons.) By 1336, it had ceased to be a state and devolved into various rival tribal groups.

Early on, Timur played politics, figuring out which of the various small-scale Khans to support. At this point, he was no conqueror—he was an impoverished nomadic warrior. While he and his band were rustling sheep, a pissed-off shepherd fired his bow at Timur, piercing him twice. He was hit in the hand and in the leg, giving him a permanent limp. Because of this, he became known among his foes as “Temūr(-i) Lang” which in Persian means Timur the lame, from which comes the name under which he came to be known in Europe, Tamerlane. He was a brigand of minor noble heritage who ended up allied with the Emir of Chagatai and involved in local politics. He overthrew the unpopular Emir, assassinated him, and married his widow, Saray Mulk Khanum. She was a direct descendant of Genghis Khan, which brought Timur prestige—it allowed him to call himself a “Güregan”, or honorary son-in-law of Genghis. Timur called himself “Emir” instead of “Khan” –only direct male-line descendants of Genghis Khan could be called “Khan.” If Timur had simply revived the Chagatai Khanate as a Muslim Turco-Mongolian regional power, he would be barely remembered today—and he certainly wouldn’t have had plays written about him in England.

Timur was illiterate but intellectual. He is famous not only for his diplomatic correspondence with other potentates (especially the Ottoman Sultan Beyazid I), but also with intellectuals and poets. He also was a devoted chess player who invented a variation on the basic game.

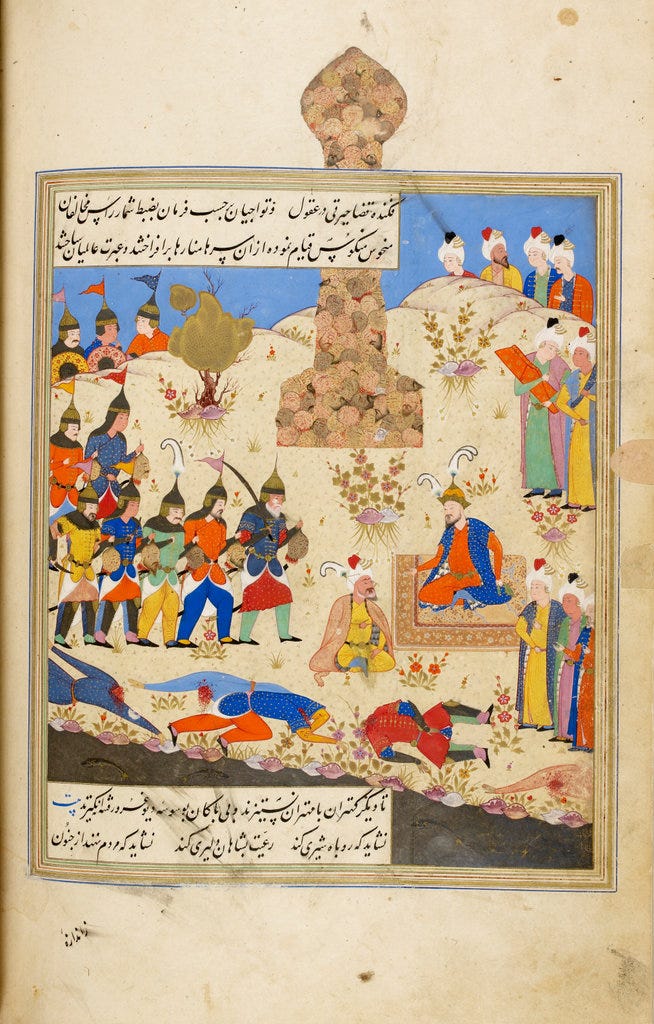

I haven’t found any images of Timur made while he was alive. One finds a lot of European orientalist paintings depicting him as a cruel and exotic Asian tyrant, as in this 1878 picture by Stanislaus von Chlebowski. The earliest images of Timur I’ve found were from an illustrated biography of him commissioned by one of Timur’s grandsons, Ibrahim Sultan, and completed in 1436, 31 years after the conqueror’s death. This biography, the Zafarnama, was written by Sharaf al-din 'Ali Yazdi and the calligrapher is Siraj al-Husaini. (I mention both because in a typical medieval Persian illustrated manuscript, who did the illustrations? The information on museum websites is unclear about this.) Timur is depicted with a beard and mustache, a pointed hat or helmet, and isn’t depicted as disabled. But this book is a panegyric, so one can assume that it attempts to portray the tyrant in a flattering light (although they do illustrate some notable atrocities). In 1941, the Soviet Union opened Timur’s tomb and transported the skull back to Moscow, where archeologist/anthropologist, Mikhail Mikhaylovich Gerasimov tried to recreate his face as a sculpture based on his skull. I don’t know how accurate this type of reconstruction is. But Gerasimov leaves us with an image of a terrifying warlord.

Once he had secured power in the remains of the Chagatai state, he wanted more. In the 1370s, Timur invaded Khwarezm on the northern edge of Persia. His strategy was typically Mongolian. When Timur and his army approached a city, if it surrendered without fighting, the lives of its inhabitants would be spared. If the city’s political leaders chose to fight, Timur would kill every person in the city (except for those taken as slaves). I find this Mongol strategy puzzling. I understand the need to strike fear in potential conquests further on down the road, but people in cities have a value. They make and do things. If you are a conqueror, wouldn’t you want the people you conquer to continue to make and do things? Things you could then tax? But I realize to think in these terms, I am looking at the Mongol strategy through a modern lens of economics—Timur was a medieval man.

Urgench is a city located in Khwarezm. A very unlucky place. In 1220, it was sacked by the Mongols, resulting in what Simon Montefiore described as possibly the largest massacre in human history. In the 159 years since that event, Urgench somehow revived. (The history of Urgench between 1220 and Timur’s conquest must be grimly fascinating.) Timur conquered the city in 1379. They revolted and Timur returned. To conquer the city again, he demolished its walls. Then he rebuilt them, mortaring the defenders in the walls alive. This would become one of Timur’s signature atrocities. The city revolted again in 1388 (why? They must have known it would end badly). Timur razed Urgench to the ground. He destroyed their irrigation system (the irrigation systems of Central Asian cities were very sophisticated operations.) He killed all the inhabitants. Urgench remained an ex-city until it was reestablished in a different location by the Russian Empire in the 19th century as a trading post.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Great God Pan Is Dead to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.