Modern society decided that art by one person is valued more than collaborative art or anonymous art. At some point, we started to devalue collaborative arts, and we even developed elaborate theories to hide the cooperative nature of some art: for example, “auteur theory.” We somehow value teams less than individuals—at least as far as art goes. The exception to this rule is for partnerships—the Bechers, Gilbert & George, Allora & Calzadilla, Elmgreen & Dragset, and others. Here in Houston we had the Art Guys, and Lubbock has the Wheeler Brothers. The Wheelers are Jeff and Bryan. Bryan describes their collaborative process like so: “Jeff would drop a piece that he started in my studio, and I’d occasionally do the same. We would add a little at a time, passing it back-and-forth, until it was ‘full.’ We never did and still don’t plan them or talk about them in process.” It feels as if Jeff Wheeler more-or-less reproduced this method for Texas Collaborations With Jeff F. Wheeler at Heidi Vaughan Fine Art, in which Wheeler worked with 12 other artists.

One of his collaborators in the exhibit is James Surls, the great Houston sculptor. Wheeler and Surls have a longtime relationship. In 2017, Surls and partner Charmaine Locke were building an art center that was to be called Splendora Gardens. Wheeler was hired to be the director of programming. After about a year on the job, Wheeler had a difference in opinion about the direction of Splendora Gardens and abruptly left the gig. (In the intervening years, Splendora Gardens has been renamed the Locke Surls Center for Art and Nature.) Whatever argument Wheeler had with them in 2017 didn’t prevent him from working with James Surls on several collaborative artworks for this exhibit. Just Outside Splendora #1 quotes Pablo Picasso’s Two Women Running on the Beach (The Race) (1922) twice as a collage element. The diagram-like lines and dots in the center of the composition are typical of Surls’ drawings. One of the pleasures of this show is that you see one artists’ trademarks—whether stylistic or technical—shine through. So Surls’ quasi-scientific biometric designs stick out in a way that feels different when you encounter them in artworks that are solo Surls. For the most part, Wheeler and his collaborators are not going for a smooth blending of styles—these are not the kind of collaborations where a brushstroke initiated by the first artist will be completed by the second. If you see portions of the artwork that look like they were created by Surls, they probably were.

But that clear bifurcation between artists’ respective styles is not always visible. In Gary’s Fifth Grade Class, someone carefully painted little blank portraits of children as if in a yearbook, but I have no idea if the painter was Gary Sweeney or Jeff Wheeler. My guess is that Wheeler painted the faces, because the art I’ve seen from Sweeney seems to be mostly assembled or collaged out of existing commercial signage. But if they are based on actual photos of actual children that Sweeney attended elementary school with, one might guess that Sweeney painted them.

A grid of identical photographic portraits feels like a universal ritual of growing up in the USA that it becomes an especially fertile starting point for an artistic question about the passage of time. Sweeney’s inferiority complex reflects his working class life—he spent 35 years as a baggage handler at an airport. There is a category of jobs that artists take to support their passion—think of the waiter gigs that actors and other performers take early in their careers. Sweeney’s baggage handler job is a truly heroic example of this practice. We can’t tell by looking at these drawings of early 60s children if Gary’s classmates had bourgeois futures ahead of them, or if they would be working stiffs like Sweeney. In a way, this backwards look at ones personal history reflects a big part of Sweeney’s artistic practice—it seems that his best-known piece, America, Why I Love Her, is composed in part of old Sweeney family photos of various family vacations taken over the years by the Sweeneys.

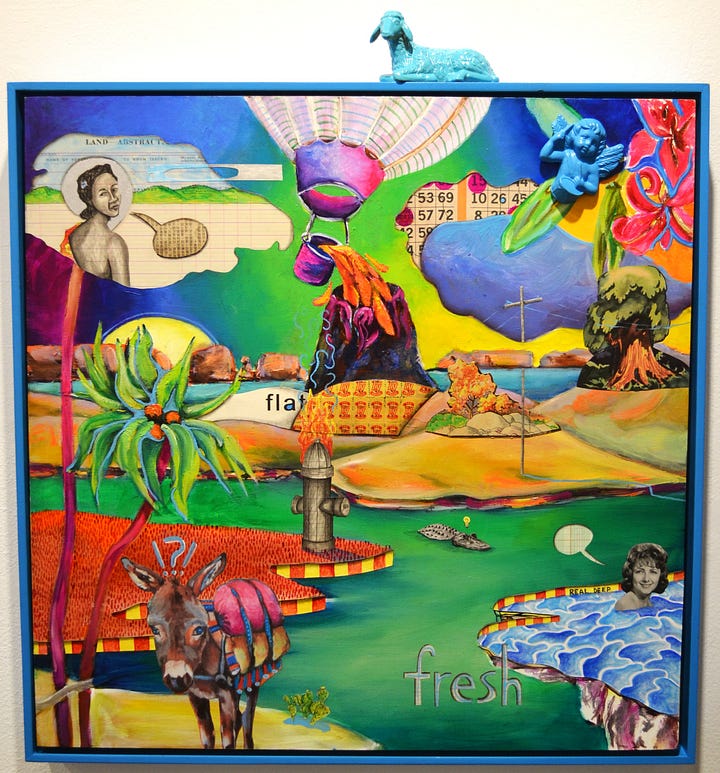

Janice Freeman is a Houston artist who has specialized in somewhat surreal, brightly-colored landscapes, which she carries forth in her collaboration with Wheeler. Ricky Armendariz is a San Antonio artist who specializes in wood block prints, but at some point realized that the blocks themselves looked cool, and started making artworks that juztaposed a painting on wood and an incised image. He calls these “carved paintings”. His woodcut of a crow resting on the eyeholes of a skull is pasted onto a sandy desert landscape with an ominous man-made pool in the foreground, reminding one of the old Western cliche of a sign labeling a watering hole as bad if it contained toxic quantities of arsenic. Susan Budge is a ceramicist who makes often very totemic pieces. As with Freeman and Armedariz’s pieces, Budge’s artistic approach dominates the collaboration. (The tile of her collaboration, Supersonic Star Baby No. 1, amusingly suggests that there are more Supersonic Star Babies.) Wheeler could have driven the boat more, but he often seems to have generously permitted his collaborators to occupy the foreground. Jeff Wheeler’s longtime collaboration with his brother is represented in several pieces, including Novel Toys, Tricks and Games. They feel like equal partners in their collaborations.

I know that Hills Snyder is a San Antonio-based artist whose work, as far as I’ve seen, consists of installations and colored-pencil drawings on paper. Standing Figure With SUV appears to have been made via the process described by Bryan Wheeler above—the vellum sheet passed back and forth, with each collaborator adding a new element on each pass. I am curious about which artist shot the vellum, and what the artist who received the gunshot drawing next thought when he saw it. It feels like one of the collaborators could have been sending a message or a warning to the other. It suggests a level of machismo, which for Texas artists of a certain generation seems to be a common element.

This is a small sampling of the art of Jeff F. Wheeler and his collaborators on display at Heidi Vaughan Fine Art through May 10. Mostly nothing too serious—just a bunch of artists having fun with one of their friends.

[Please consider supporting this publication by becoming a patron, and you can also support it by patronizing our online store. And one more way to support this work is to buy books through The Great God Pan is Dead’s bookstore. ]

I wonder if Jeff Wheeler saw this yet! It's a nice bit of writing about the show. I'll post it on his instagram in case he hasn't.

I know about Jeff Wheelers work because I have been a big fan of Daniel Johnston since I was a kid and the two of them collaborated together. That's what I asked him about when I had a second to talk to him about the show, how he ended up doing that collaboration. Fun.