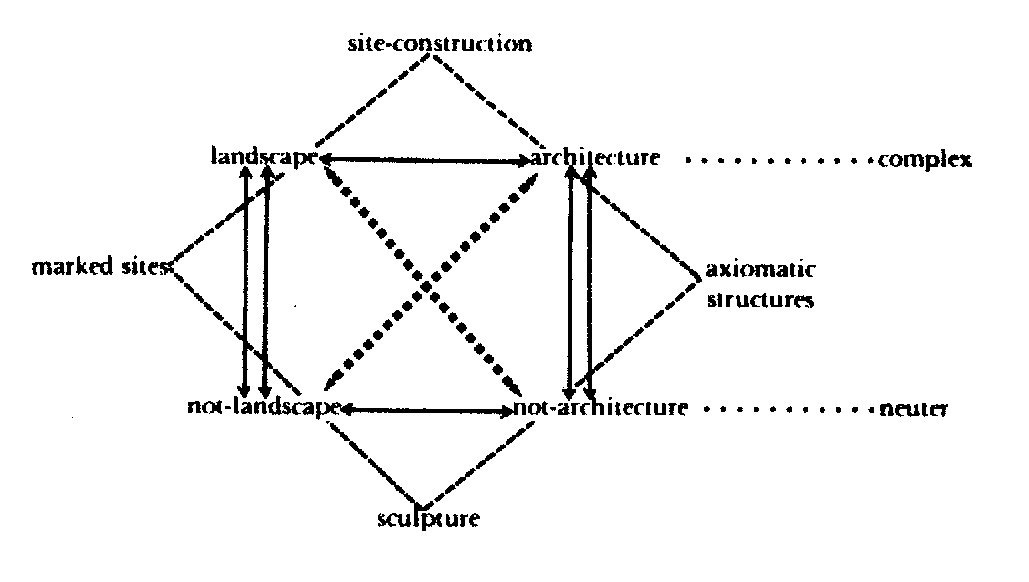

When I saw Patrick Renner’s exhibit at the AIA Houston, something occurred to me that now seems obvious, but which I had never thought of over the many years I have been following his work. Patrick Renner is a builder, obviously, but as he designs what he builds, he is an architect. This realization means accepting that sculpture overlaps with architecture. But this isn’t how we used to think about it. Modernism gradually broke down such distinctions throughout the 20th century, especially in the 60s and 70s with the rise of site-specific artworks, earth works, and installations. Weirdly enough, this was expressed as a theory in 1979, by which time it stops being a theory and is more of an observable fact in the world. In her famously abstract essay, Sculpture in the Expanded Field, Rosalind Krauss essentially proposed that modernism had completely obliterated the distinctions between landscape, architecture, and sculpture.

By the time Patrick Renner completed his art education (MFA from Alfred University in 2006), all contemporary sculpture existed in the expanded field described by Krauss. And Renner’s technique of using scrap building material led to anther influence—mud daubers. Renner wrote:

The stacks of wood in my studio were apparently ideal for nest-building wasps, as more and of the curious little clumps of earth were constructed among my material archives. As well as clinging to the walls and eaves of the studio. Even the name of these creatures captured my imagination: mud-daubers.

Inspired by his wasp studio mates, he built a sculpture called Wooddauber, which was one of the first works by Renner that I ever saw. Like a mud-dauber’s nest, Wooddauber has a curvy shape with little round holes in it, which are the entrances and exits that the mud-dauber builds into its nest. With its layers of laminated word stripes, each a different color, which would become a trademark look of Renner’s subsequent work. When he first constructed Wooddauber he ended up with a bunch of leftover discs made of laminated bits of wood. Renner’s work depends on creative reuse of materials, which evidently includes reusing materials that he made. He turned this discs into tiny sculptures called Core Samples. In the field of oil drilling, a core sample is a tiny cylinder of rock that has been removed from a oil well being dug so that geologists can take a look at the kind of rock the drill in passing through. Renner essentially created fake, bright pastel colored versions of a common piece of oil field detritus. I bought one of these from that exhibit at Avis Frank gallery in Galveston. I was working at an oil producer at the time and figured it was appropriate.

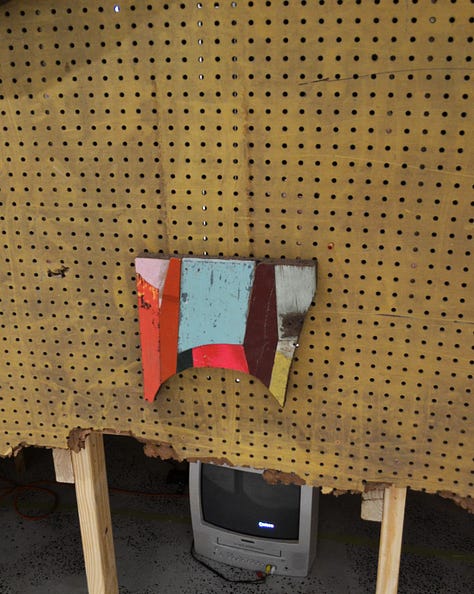

Shortly after seeing that exhibit, I saw Bounded Operator (Chamber #4), a sprawling installation at El Rincon Social. As with the Core Samples, geologic time was a subject of this work. But perhaps more important was the constructed nature of the work. It sprawled over more than one room within El Rincon Social’s grimy, cluttered interior. Thinking about Renner’s work in the various locations I’ve seen it, one wonders how well it would work in a gleaming white cube gallery.

When a sculptor like Renner makes an indoor installation like Bounded Operator (Chamber #4), he is acting a little like a contractor, dragging tools and building materials to change an already existing space into something different. Renner’s changes are temporary, though. His kind of installation sits somewhere between hanging a painting and having an architect come in and start knock out walls for remodeling job. This was the first Renner project I saw that I’d call a species of architecture. It was the first of many.

The next year, Renner produced the work that would make him locally famous. He built the Funnel Tunnel, a block-long sculpture of a horn made of multicolored strips of wood. It reminded me a little of the long imperial horns produced before valves for horns were invented in the 19th century. You can imagine a dressed up footman in a royal court blowing one of these. Because it was in a highly public place and because it was so big, people driving up and down Montrose had to notice it. And while it was a built object, it can only be compared to architecture loosely. I think it would be fair to say that it fell between sculpture (as it was defined before modernism and landscape.

Renner took the idea of Funnel Tunnel and expanded it in several other works. Hot Droop (2014) took the idea of a gradually expanding cylinder and attached to a window of a suburban house. Harbinger (2016) had the cylinder issuing from a billboard, made of Renner’s trademarked wood strips. The cylinder warps around the billboard and tapers off before it swallows itself. It is like an Ouroboros being born, at just the instant before it devours its own tail. I didn’t see either of these two in person—I don’t know if they were made in Houston. I see this strain of Renner’s work as approaching architecture, but not quite there.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Great God Pan Is Dead to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.