It feels hard to believe in these post-print times, but millions of Americans read comics every day in their newspapers for most of the 20th century. Comics strips were possibly the most popular form of entertainment for many decades. So among my 100 comics that I discuss in this newsletter, comic strips will be much honored. The first I will discuss is Terry and the Pirates, a comic strip by Milton Caniff that ran from 1934 to 1973, but we are only concerned with the years Caniff wrote and drew it. He left the strip in 1946, after being lured away from the Chicago Tribune to the Chicago Sun Times for better pay and more creative control. The strip he created for the Sun Times was Steve Canyon, a cold war adventure strip.

Caniff was hired to write and draw a boys adventure comic strip set in China. The setting was the choice of Joseph Patterson, the publisher of the Chicago Tribune. Caniff took the suggestion and ran with it, devising a weird set up in which a young boy, Terry Lee, is an orphan who is being taken care of by an older man Pat Ryan. The uncomfortableness of this arrangement is more obvious to modern readers than it was to comic strip readers in the 1930s, apparently (they thought nothing of Batman and Robin, for example). The setting of China was reflective of the fact that there were no unexplored parts of the world in which to send your fictional preteen adventurers to discover. It was in a way the tail end of a genre of imperialist boys adventures. China was exotic and foreign enough.

When he started the strip, the characters were pretty thin cliches of adventurers, drawn in a fairly basic but highly competent drawing style, that resembled book illustration. Caniff shared a studio with another artist, Noel Sickles, who was experimenting with a dramatic chiaroscuro drawing style. Caniff liked what he saw. His artwork on Terry and the Pirates quickly changed from somewhat genteel to dramatic and noirish. In this way, he seemed to be unconsciously reflecting a change in American culture. Terry and the Pirates was to earlier boys adventure comics what James M. Cain was to Agatha Christie.

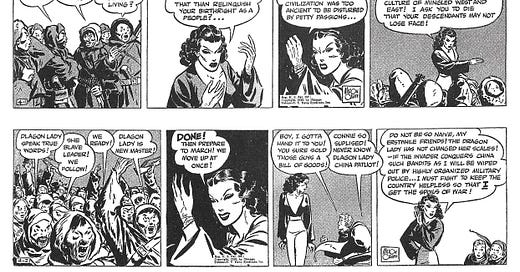

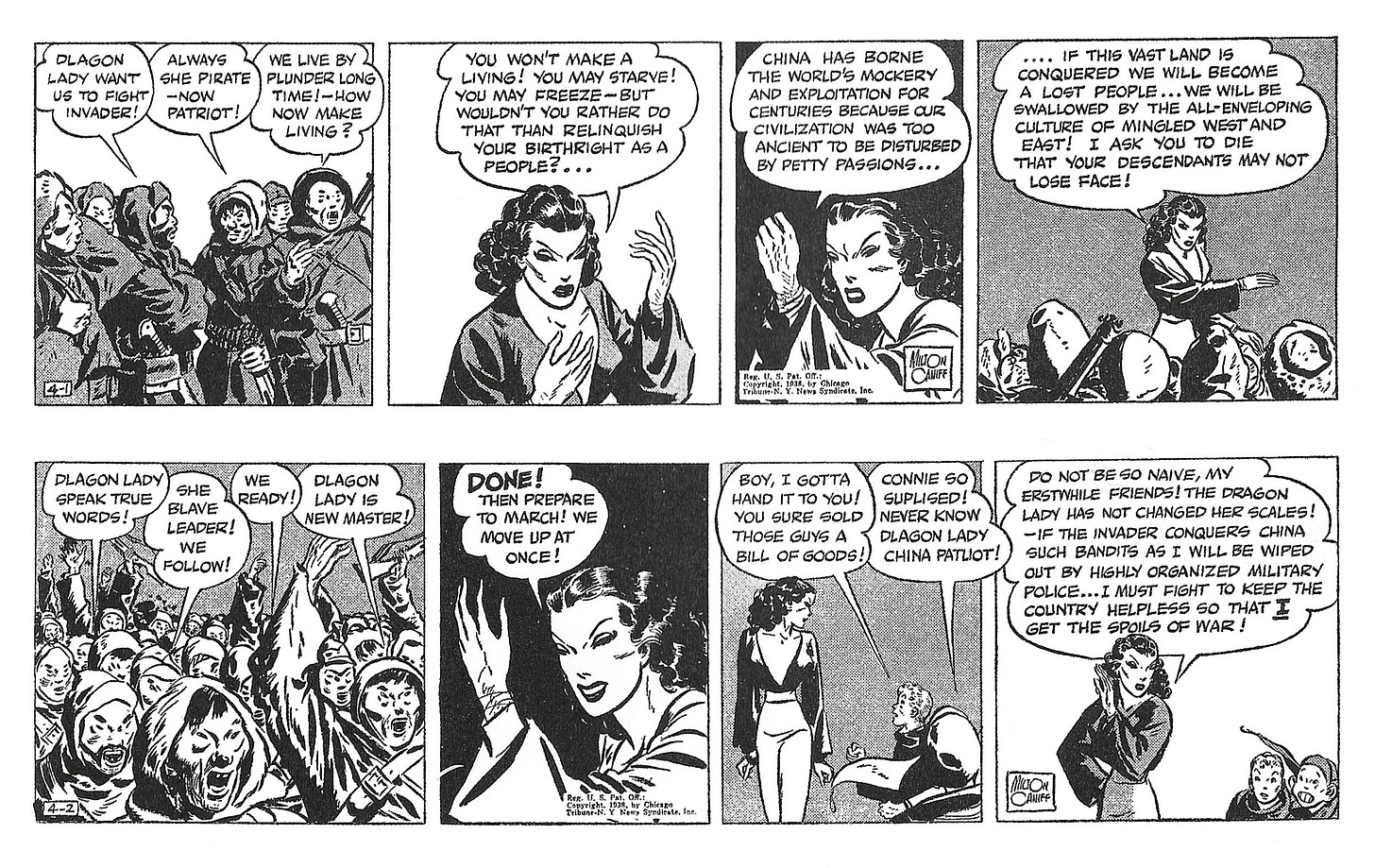

Additionally, he evolved the feeling of the strip. The characters ceased to be stock adventure story players and became much more rounded—it would be wrong to say that they were quite “fully fledged”. (It was Caniff’s ability to create memorable characters that distinguished him from Sickles, who was perhaps the more talented visual artist.) And the Chinese characters remained crude caricatures—one of the hardest things for a modern reader to take is Caniff’s racist attitude. But, as often as not, Chinese characters are heroes. He does engage in rank orientalism, making Terry’s primary antagonist an exotic Chinese pirate known as the Dragon Lady. But he turns her into a patriot for China by the end.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Great God Pan Is Dead to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.