When I was a kid and needed to get cleats to play football, I almost always went with mom to a sporting goods store called Oshman’s. Oshman’s was a local chain that existed from 1933 until 2001 when it was bought and changed its name to Sports Authority. Jake Oshman was a Latvian immigrant who started out with a dry goods store in Richmond, a small town outside of Houston. The first generation builds the fortune, and the second generation becomes art patrons. His daughter was Marilyn Oshman, who became one of the most creative art patrons ever in Houston.

I always feel a little weird when I read tributes to great art patrons because it feels like a suck-up to the rich. And what is their accomplishment, really? To have good taste and the willingness to spend money on it? But there are other classes of people who do the very same thing that I greatly admire—editors, curators, producers. A great patron is a little like a Maxwell Perkins or Marcia Tucker or Rick Rubin or Serge Diaghilev—someone with enthusiasm and the desire to nurture great works of art.

Therefore let us pay tribute to Marilyn Oshman.

I think of Oshman in relation to three things: The House of the Century, a bizarre structure designed for Oshman by the Ant Farm; the Contemporary Arts Museum and the coming of Jim Harithas; and the Orange Show.

Back in the 70s, Oshman was a volunteer at the newly constructed Contemporary Arts Museum when two disheveled hippies walked in and asked to speak to the director. They were Doug Michels and Chip Lord, two young architects who started an artistic partnership a couple of years earlier. Their goal was to be “underground architects,” an ambition that inspired the name of their collective—the Ant Farm. Her CAMH colleagues were unimpressed, but Oshman was intrigued. She told the Dallas Morning News, “That was the beginning of a huge turn in my life.”

Oshman was no hippie, but she invited the two oddball longhairs to do a performance at a fund-raiser for the museum. This was the start of a friendship. A year or so later, Michels was visiting Houston and Oshman told him that she and her husband were thinking of building a lake house, and Michels volunteered the Ant Farm to design it. The group had previously designed no permanent structures—they were known for their inflatable structures. But they were trained architects, so Oshman and her husband hired them to build their lake house.

Having zero building experience, Ant Farm worked with a friend of theirs, Richard Jost, to figure how to construct this very futuristic, curvy building that they were proposing. They were influence by Antoni Gaudí and 2001: A Space Odyssey. And like the main spaceship in 2001: A Space Odyssey, this lake house looked like an erect penis.

Eventually the house was flooded and vultures squatted in the ruins. But as far as I know, the ruins are still there. Mojo Lake is private property—you can’t just go and visit the House of the Century. Ant Farm returned to California, but they had obviously built ties to Texas—their best-know artwork is Cadillac Ranch, near Amarillo.

The Contemporary Arts Museum opened in its current location in 1972. Its first director, Sebastian Adler, was fired the same year, leading to a crisis for the brand new museum. A museum with no one to run it is a problem and an opportunity. Oshman was now a board member and was involved in the search for a new director. On a trip to Milwaukee to research museum bookstores, she heard a talk by James Harithas, a director of a small museum in New York State. Oshman found him inspiring, and hired him away from the Everson Museum to come to Houston. This by itself makes Oshman a great patron, because she chose correctly. Harithas had an indescribable effect on the Houston art scene.

Marilyn Oshman’s patronage of the Orange Show is perhaps her most important contribution to Houston’s art scene. The House of the Century is an inaccessible ruin, Harithas’s influence still lingers but the two museums he founded, the Art Car Museum and the Station, are now gone. The Orange Show is still there, is in the process of expanding, and very much involved with Houston’s artists and creative community. In a way, it feels more vital to Houston’s art life now than ever before.

Jeff McKissack was a mail deliverer who lived on the East Side of town. He would pick up discarded objects while on his rounds, and he started to construct a bizarre, home-made castle which he called the Orange Show. He intended it to be a tourist attraction devoted to the health effects of the orange. As he was constructing it, Oshman became aware of it. After McKissack opened it to the public, with unrealistically grandiose ideas of how successful this monument to the orange could be, he only lived another nine months. As McKissack was building it, Oshman offered him money to help pay for permits. He wouldn’t accept it, but he did produce artwork for her that she bought. So the fact that the Orange Show even got built is partly due to her patronage of McKissack.

After McKissack’s death, Oshman raised money to buy the structure and set up the foundation that owns and runs the Orange Show. Presumably her experience with the CAMH helped her figure out what went into running a nonprofit, with a board and staff and volunteers. When we think of naive art or visionary architecture, there are two stories—the story of the artist and the stories of the people that discovered the art. The stories of McKissack and Oshman are told in Painting the Town Orange, a book about visionary art environments in Houston written by Pete Gershon, who is now the curator of programs of the Orange Show.

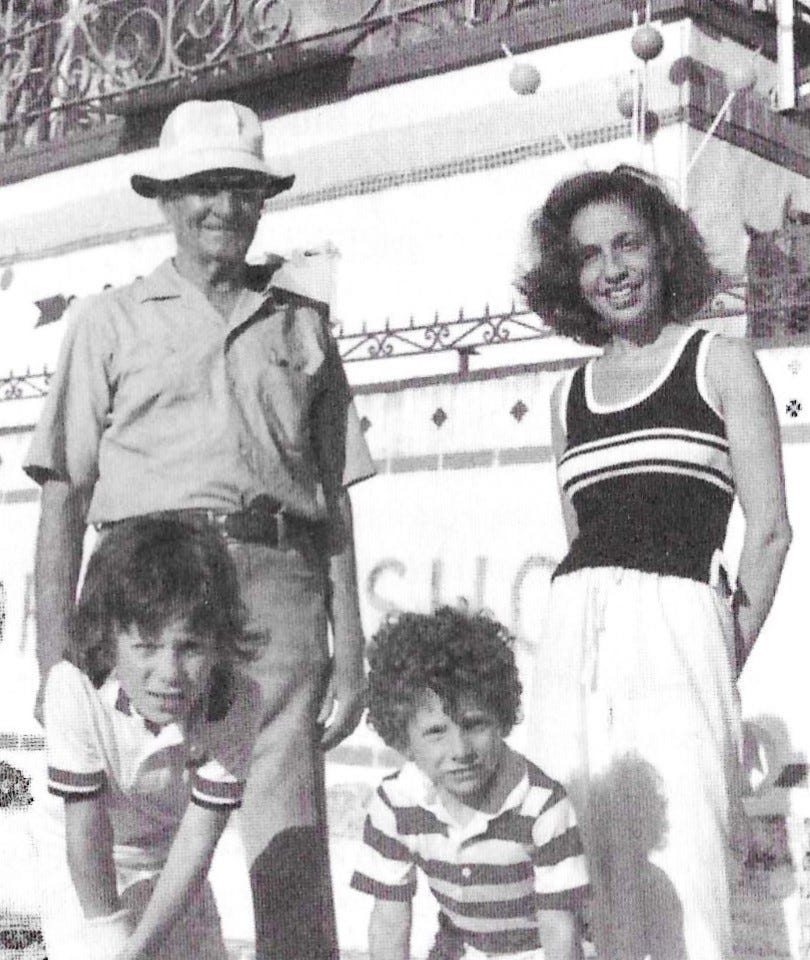

In researching this post, I came across a substack post by Kim France about Oshman. She mentions that around the time Oshman was building the House of the Century, she was purchasing two Frida Khalos and a Diego Rivera. France describes Oshman’s River Oaks home as “an art-filled funhouse—there was an entire room devoted to an Edward Kienholz, then also a John Chamberlain or two, and a vintage 50s photo booth in the living room, a gift from one of the guys in ZZ Topp, who Marilyn dated after splitting up with our uncle Alvin.” I wish I had known Marilyn Oshman, a great Houstonian.

[Please consider supporting this publication by becoming a patron, and you can also support it by patronizing our online store. And one more way to support this work is to buy books through The Great God Pan is Dead’s bookstore. ]

Wow, I had no idea about any of this! Thanks. We had an Oshman's in San Antonio where I grew up that we frequented. So I'm going to take a little bit of credit in that the shoes we bought there helped pay for all of that. You're welcome. ;)