Sonya Clark is a fiber artist. “Fiber artist” is a description that feels slightly demeaning considering how expansive her practice is. She has an exhibition at two venues simultaneously. We Are Each Other is on view at the Houston Center for Contemporary Craft and the Houston Museum of African American Culture.

Clark’s artwork involves lots of audience participation and collaboration with other artists (especially poets and, weirdly enough, hairdressers and barbers). Many of her projects include community participation. And the history of slavery is a subject she returns to frequently in her work in moving and sometimes funny ways (as in her various recreations of the Confederate truce flag, for example). Some of her work involves reclaiming a black space in a world that European culture that has dominated. In short, We Are Each Other is political in a way that speaks directly to the situation we currently find ourselves, where our rulers are now a group of white-supremacist Nazi freaks.

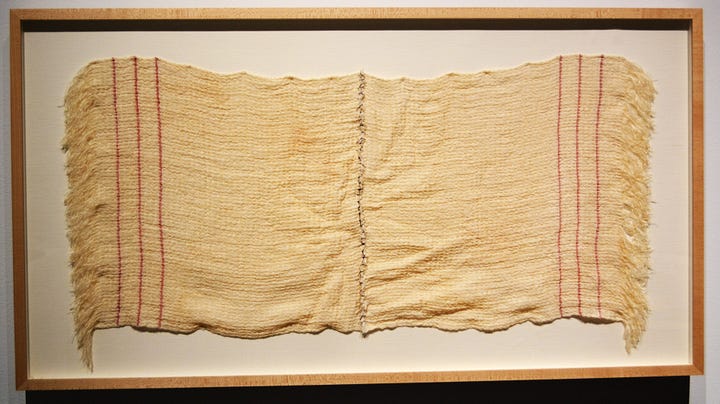

When Clark was a research fellow at the Smithsonian, she came across the Confederate truce flag which Robert E. Lee and party used to safely walk through the Union army camp at Appomattox to negotiate surrender terms. Given the ubiquity and popularity of the “stars and bars” among lost-causers, racists, and members of the Trump government, the Confederate surrender flag felt very meaningful to Clark. A monument is a public declaration of something a society chooses to remember—Clark concluded that the surrender of the Confederacy and the end of the legal enslavement of black people was worthy of a monument. As a fiber artist, her monuments to this historical event take the form of a piece of fabric, that modest truce flag—sometimes stretched out, as in the enormous “scrolls” above.

If the truce flag is to be a monument, it is necessary to manufacture a lot of them to fly in as many town squares on April 9 (the day Lee surrendered) as possible. She has begun the project of mass production of the surrender flag in Many. Apparently after the surrender, Union general George Custer cut the flag into pieces, keeping a large piece for himself (which is now in the Smithsonian) and giving the smaller pieces to soldiers as souvenirs. Clark imagines repairing the dismembered truce flag in Monumental Cloth (Sutured).

The actual truce fag is an ordinary object, quite tiny. It can only be monumentalized by assigning it a profound historical meaning. Clark wouldn’t mind “unmonumentalizing” its better-known counterpart, the Confederate Battle Flag.

Unraveling is a performance in which visitors carefully unraveled the threads making up a Confederate battle flag. Destroying a flag is pretty easy, but unraveling it thread by thread is obviously laborious and difficult. The difficulty mirrors the long (and thus far incomplete) labor of destroying the slavocratic ideology of the South. It is a task that Clark returns to frequently.

The Confederacy lingers in unexpected ways. Benjamin Moore used to have a shade of paint that they named “Confederate Red.” I don’t quite get the association of red with the Confederacy, but Benjamin Moore apparently found it a commercially viable name for a color of house paint. After being sued by a black employee, Benjamin Moore changed it to “Patriot Red.” Clark has made a gigantic paint chip out of Benjamin Moore’s weird color name, reminding us that as late as 2014, that a major American consumer-facing company still thought associating itself with the Confederacy was good business.

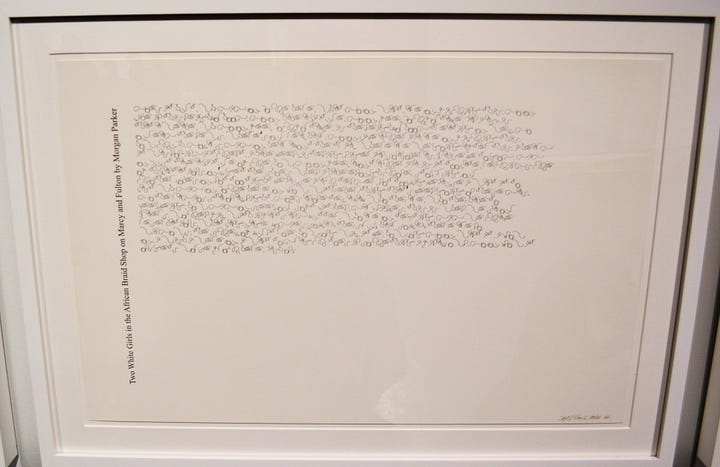

In 2016, Clark collaborated with designer Bo Peng to create a new alphabet based on strands of Clark’s own hair. This is intended to be an anti-colonial gesture, as the Latin alphabet was imposed by the Western colonial powers. Devising a new font, Twist, is one way to reclaim that space. But it only works if this script is actually used to write stuff. So in 1-877-OUR-CURL, Clark rendered her font into cast-metal moveable type so that she could produce letterpress printed texts. The texts she produced were poems by several black femme poets.

It does seem that rendering poems into an unreadable script obviates their purpose as literary objects, so to by calling 1-877-OUR-CURL, viewers can hear each poem read aloud.

The exhibit takes its title from a line in a poem by Gwendolyn Brooks called “Paul Robeson.” It is printed on the wall in the Latin alphabet and in the Twist alphabet. Just as Brooks paid tribute to an older African-American artist in writing “Paul Robeson”, Clark continues that practice of honoring older artists in 1-877-OUR-CURL. This chain of respect feels especially necessary as Trump and his allies seek to erase the visibility black artists’ work. We see this erasure already in the cleaning out of libraries.

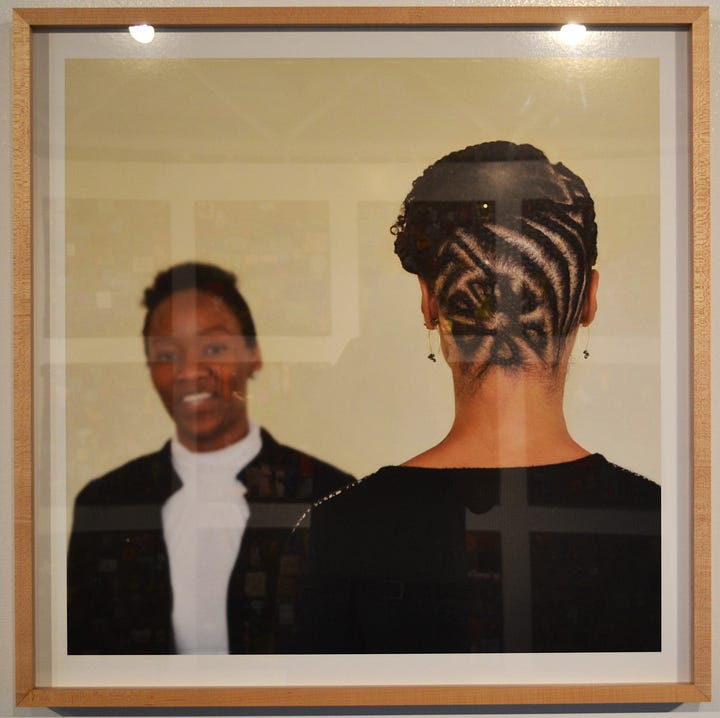

Twist with its basis in hair points to another focus of Clark’s artistic practice—black hair culture. In The Hair Craft Project: Hairstylists With Sonya, Clark presents a series of photographs with two female figures each represented roughly from chest high. The figure on the left is facing the viewers while the one on the right is facing away in a pose that shows off the back of her head. The figure on the left is standing slightly further from the viewer than the one on the right, and due to the depth of field setting, the figure on the left is slightly out of focus while the figure on the right is sharp. In each photo, the figure on the right is a hairstylist and the figure on the left shows off an example of the hairstylist’s work.

As with Clark’s renderings of the poems in 1-877-OUR-CURL, The Hair Craft Project: Hairstylists With Sonya seeks to pay tribute to other artists within the black community. But unlike the artists honored in 1-877-OUR-CURL, the hairstylists are not members of the artistic elite. A hair stylist is a member of the working class whose art is ephemeral. Within the bounds of this exhibit, Clark is placing braids on the level of poetry. She immortalizes this art and the artists who produce it.

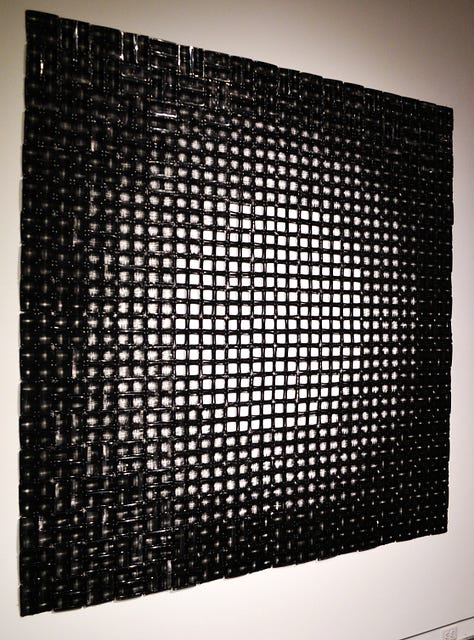

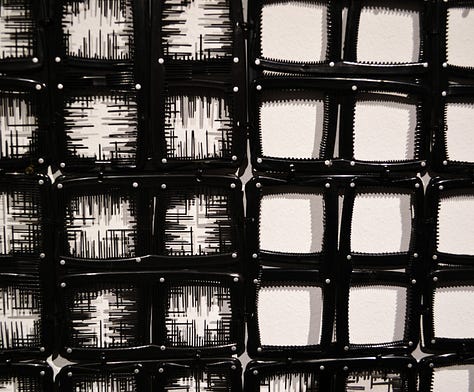

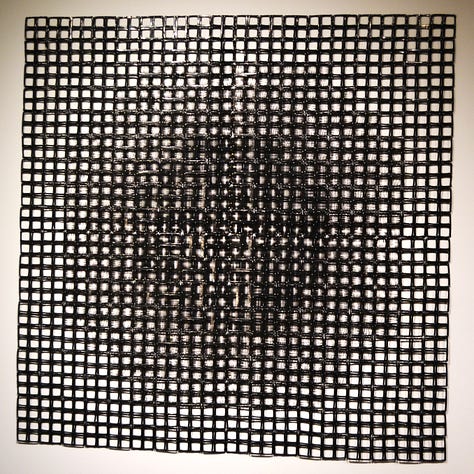

The tools of a hair stylist are memorialized (and monumentalized) in two large found object wall sculptures, Hole Whole and Whole Hole. Both are constructed of hundreds of well-worn (if not completely busted) combs. Clark uses the teeth of the comb to create a kind of chiaroscuro which from a distance become a rough lens shape.

The pieces described above are just a small part of this expansive exhibit. The show’s Houston components were put together by Sarah Darro from HCCC and John Guess, Jr., the CEO of HMAAC. Guess is the founder of the Guess Group, a large commercial real estate firm in Houston. Guess and his partner Melanie Lawson are two very active art collectors in Houston. They go way beyond the rich hoarder types we imagine filling the seats at Sotheby’s and Christie’s. They are very active patrons of the type Marilyn Oshman or the Menils were. They aim to make a tangible impact on their world.

I first became aware of John Guess when he and Lawson sponsored an exhibit of their collection in the downtown offices of Gensler, a huge architectural design firm earlier this year. It was a weird place to have an exhibit (it is a working business office), but their collection was pretty amazing. When I visited the exhibit early this year, I had no idea who John Guess and Melanie Lawson were, but I was intrigued by the work displayed. I wrote to the email address for the collection, expecting to hear back from an administrator, not from the plutocrat who had assembled the collection. It was like getting an email from Henry Clay Frick. Guess wrote that he and Lawson want their collection to advocate for various communities, particularly the African-American community and women. (And it advocates for Houston by collecting work by a large number of Houston-based artists.)

The reason I bring up John Guess and Melanie Lawson is because I am certain that nonprofit art organizations like HCCC and especially HMAAC are in the crosshairs of the Trumpists. I don’t know what portion of their operating budgets come from federal grants, but my assumption is that those grants are gone for the next few years. If we want to have great, politically-salient exhibits like We Are Each Other in the future, patrons like John Guess, Jr., and Melanie Lawson will be critically important.

[Please consider supporting this publication by becoming a patron, and you can also support it by patronizing our online store. And one more way to support this work is to buy books through The Great God Pan is Dead’s bookstore. ]

My preferences lean heavily toward illustration and representational work, but this looks incredible.