I stopped by The Orange Show to see Paul Kittelson’s delightful outdoor art exhibit, Wind Field. Wind Field consists of twenty three sculptures. They are kinetic sculptures, mostly in the form of wind mills.

This is one of them. You may have noticed that Kittelson uses the images of a horse galloping that pioneering high-speed photographer Eadward Mutbridge made in 1887. For artsy types like me, this art historical fact is very entertaining. Back in the late ‘80s, I read Charles Jencks on postmodernism. One of his points about postmodern architecture was that for such an architect, the entire history of architecture was A-OK to quote. At the time, that felt like a revelation, but now 30-odd years later postmodernism seems like an art movement designed to please art history majors. Wind Field pleased me in just this way—but you don’t have to be an art historian to enjoy it.

This piece was the only one I noticed that wasn’t wind powered. It is an enormous replica of Marcel Duchamp’s Bicycle Wheel, originally created in 1913. He made it in Paris, and in 1915, to avoid being slaughtered on the battlefields of World War I, he came to the USA. Apparently he didn’t bring Bicycle Wheel with him. Duchamp remade it several times over the years. This is just the latest version (perhaps made Ghost-style with Duchamp’s mischievous spirit communicating his intents psychically to Kittelson).

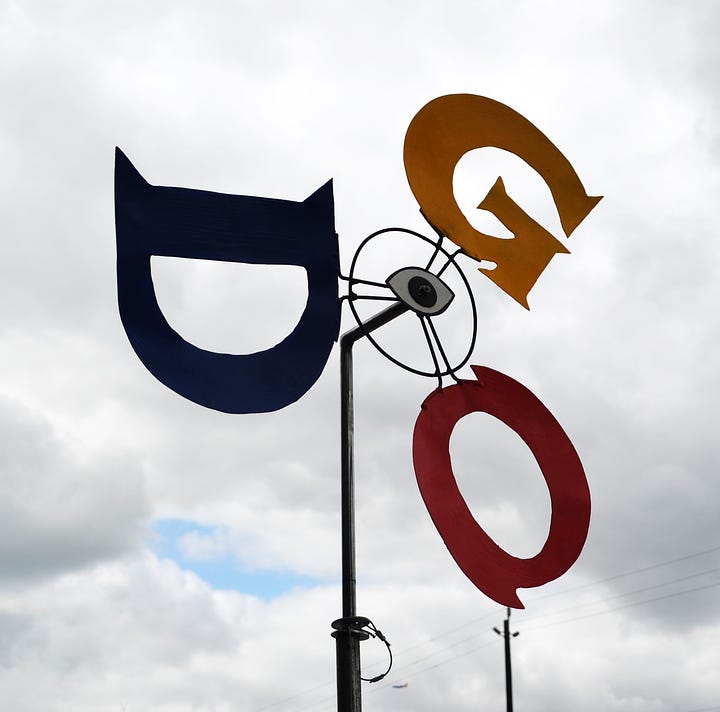

And if you are going to build a monument to Duchamp, why not add a little Warhol?

Some of the windmills were less about art history and more about graffiti.

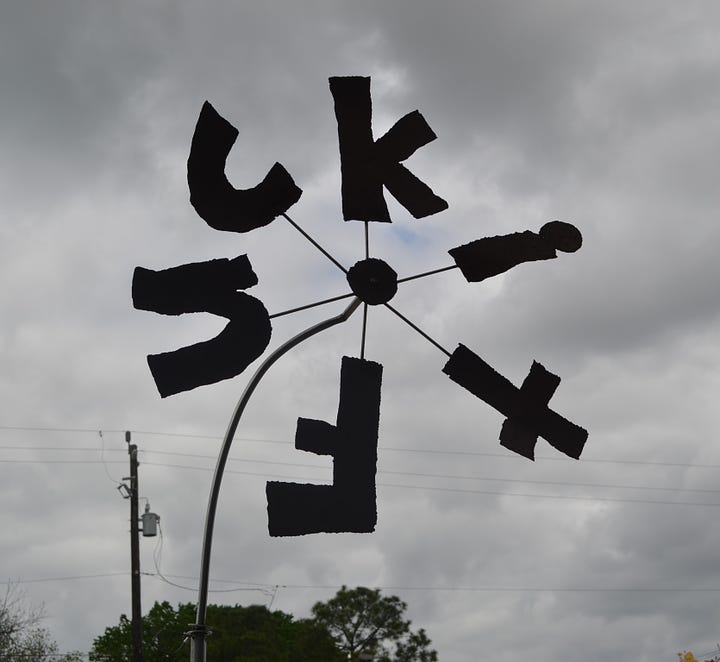

The windmill mounted on the arch reads “SOMEWHERE” In Kittelson’s amazing garden, he has another version pf the arch. Looking like a miniature version of the Gateway Arch, it is sort of a garden-size imitation of a landmark. One thing landmark’s do is tell you that you are somewhere. Other succinct messages: “FUCKIT” and “GOD”.

Several imitate early motion capture devices like a Kinetoscope. The recreation of Eadward Mutbridge’s galloping horses is one example, but there are also hand waving and strollers strolling. I like to imagine a 19th century or early 20th century person seeing something like this for the first time. It reminds me of such an incident when I was 17 and visiting colleges. Me and one of my friends were visiting Rice University, where we both ended up as undergrads. This was in 1980. They showed us the engineering lab and a device they had made that turned your voice into digital signals, processed those signals, converted them back to sound and played them at a different pitch. I was astounded, but I also thought, OK—it makes sense that technology has reached this level. (Of course, that particular technology would become ubiquitous within a year or two of my seeing it for the first time—just as motion picture technology quickly became universal.) Kittleson’s sculptures remind me of that moment before a technology exploded. Any human existing in the society of the late 20th and early 21st century has experienced this technological dislocation many times. (And most people prior to the industrial revolution almost never experienced it.)

Kittelson honors the Orange Show location of Wind Field with botanical wind mills, including one where the blades of the windmill are orange slices.

The Orange Show itself is covered with weather vanes. I don’t know if the weather vanes are Kittelson’s or if they are original decorations by Jeff McKissack when he built the Orange Show. The attic ventilators seem like original decorations, but I don’t know. I said that Wind Field is a backward-looking exhibit—it embodies art history, cultural and technological history, and Houston’s history.

[Please consider supporting this publication by becoming a patron, and you can also support it by patronizing our online store. And one more way to support this work is to buy books through The Great God Pan is Dead’s bookstore. ]