Welcome to Hell

You feel that sharp pain in your chest. You pass out. You wake up somewhere. You are laying on a plain white plain. Maybe on snow, maybe on sand. You notice that you are wearing a dark track suit and tennis shoes. You stand up and see that the plain extends forever to a dark, stormy horizon, and even over the horizon, you can see impossibly tall volcanoes. The plain on which you find yourself is interrupted here and there by enormous dark objects—are they rocks? Impossibly thin mountains? You can also see ominous sinkholes and crudely built structures. They make you think of sacrificial alters, which perhaps indicates how the sensation of gloom and dread have sneaked up on you in the moments since you came to. You see wisps of something; you can’t tell if they are smoke or dust-devils.

Welcome to Hell.

Hell and the Paradisal is an exhibit at Inman Gallery featuring artworks by Robin O’Neil. It consists of a group of small, recently-made drawings and one enormous older drawing, Hell. Hell was exhibited at the Fort Worth Modern in O’Neil’s solo exhibit there. This is a drawing on paper in three panels, with thousands of collaged elements. The size is staggering: 172 ½ inches wide by 81 3/8 inches tall.

In my review of her book, Robyn O'Neil: 20 Years of Drawings, I suggested that the little track suit men are in some vast story that leads them to these various desolate landscapes where they do things, such as hug each other or die by hanging. If they are in a narrative, then Hell is its climax. They might have been hugging before, but now their lives are consumed with violence towards one another.

In O’Neil’s other track suit drawings, the men appear to be roughly the same size. In Hell, perspective doesn’t work. Men in the foreground will be tiny compared to their peers. Tiny homunculi scamper and fight at the feet of their larger peers, at risk of being trampled at any second. O’Neil’s Hell is a dreamlike space where distant things are not necessarily smaller; a world where the visual relationship between close and far is overturned.

O’Neill spoke of her influences at her artist’s talk, and many are to be expected: Bruegel and Bosch are obvious ones, and Henry Darger comes up. Then she mentioned Robert Longo, which seemed a little out of the blue. But Longo’s figures can perhaps be related to the track suit guys. She specifically mentioned Alex Katz, which I don’t see. When I see Alex Katz art, I imagine a tranquil world of relaxed bourgeois pleasure. Very unlike the anxiety-producing images of Robyn O’Neil. The last influence she mentioned were the illustrations in the World Book encyclopedia. I was glad she mentioned that because when we try to think of the antecedents to an artists’ work, we rarely mention the mass-produced images that the artist grew up with. Her mentioning these makes me want to see the World Book volumes she saw.

In the same gallery as Hell is a vitrine containing sketchbooks O’Neil used to plan out this drawing, including a tiny but detailed thumbnail drawing. She said she went straight from that thumbnail, at most two inches high, to the enormous drawing of Hell.

This exhibit contained a series of drawings drawn this year. The story of the track suit dudes appears to be over for now. There are no human figures at all in these new drawings. The images have surreal elements in them. One was done shortly after O’Neill finished Hell. Carpets of Wind, Evermore Yours, drawn shortly after she finished Hell, is similar to Hell and many of her other works in that it shows a huge, flat horizon (whether it is over a plain or an ocean is not clear) and a looming sky with weird weather (and a black sun).

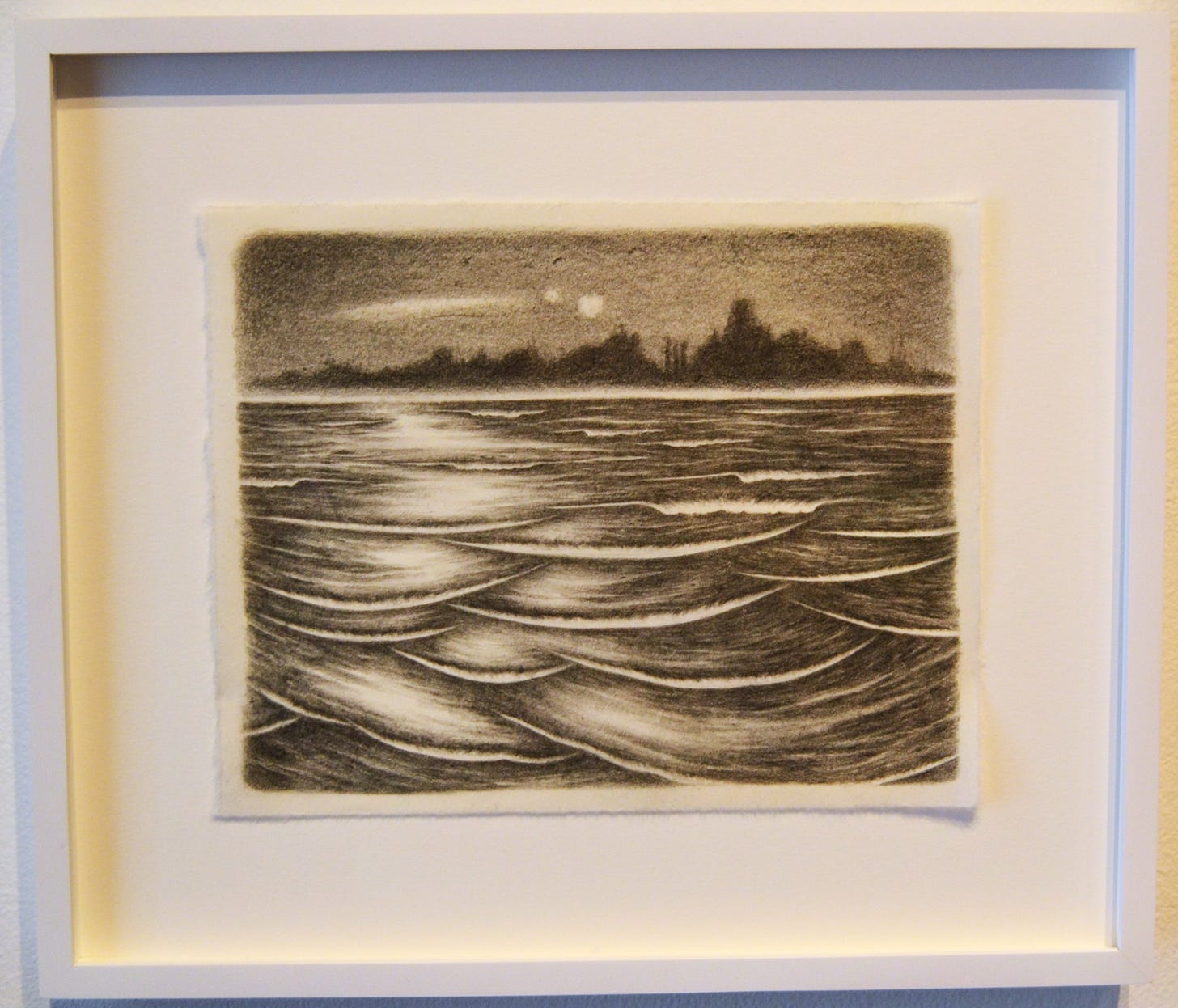

From this year, we have Nocturne, Distance, a seascape where the viewer looks out over a choppy sea to a distant shore, where the landscape is silhouetted against a grey sky. It is stylized, to be sure, but about as realistic as O’Neil gets.

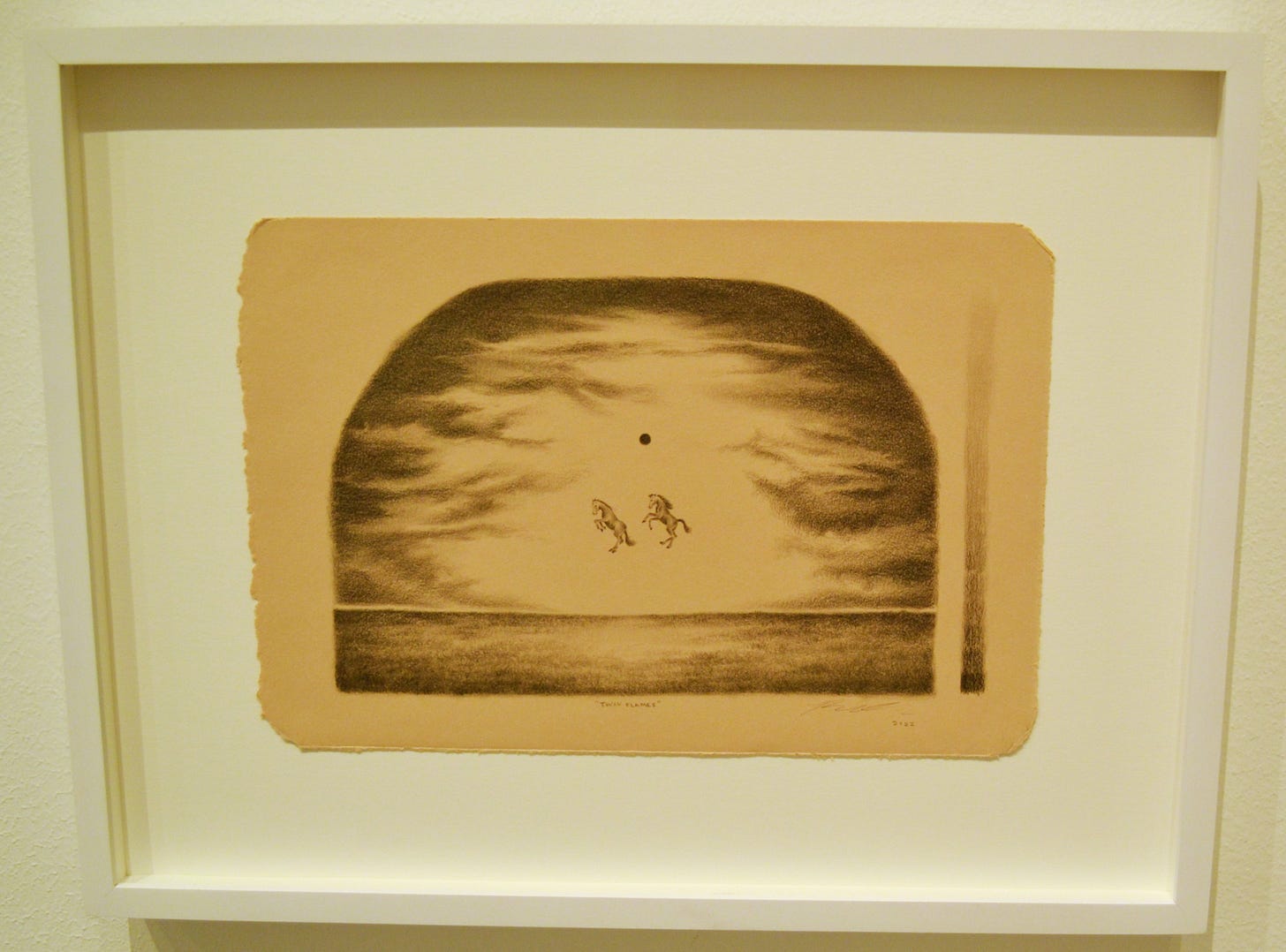

I’m going to close with one final drawing from this year, Twin Flames. It is another blank flat landscape, with a black sun floating in the center. Just below the sun are two horses, awkwardly floating in space. Horses have appeared in other drawings by O’Neil, often in bizarre unreal circumstances, like these two. She also said she was influenced by George Stubbs, the great 18th century painter of horses. One of my favorite painters.

[Please consider supporting this publication by becoming a patron, and you can also support it by patronizing our online store. And one more way to support this work is to buy books through The Great God Pan is Dead’s bookstore. ]