Every year, bloggers write about their favorite things of the year. Best movies, music, books, etc. I have done similar year-end posts for years. I used to write every year about the best art I saw. I used to diligently attend as many art exhibits every year as I could so I would have a deep well to draw from for end-or-the-year wrap-ups. But 2024 has seen me at fewer exhibit openings than I have seen for years. Open heart surgery will put a crimp in one’s attandance of art events. So this year, my year-end lists are all about books. I started with the ancient literature I read this year, and then the comics. These two categories lead naturally into my next group of books read in 2024: Turkish lit. Obviously.

In the summer of 2023, I read Snow, a novel by Orhan Pamuk who won the Nobel Prize for literature in 2006. It was a bit of a slog through some thorny political business, but I was spellbound. (I often give Nobel Prize winners a try with mixed results.) I loved Snow and wanted to explore this writer more.

So in 2024 I started a streak of Pamuk. I started with The Black Book, a humorous faux detective novel. The protagonist, Galip is a lawyer in Istanbul. His wife Rüya has mysteriously disappeared. (Appropriately, she is a fan of detective novels.) At the same time, he discovers that Celal, a columnist for an Istanbul newspaper and Rüya’s much older half brother, has also disappeared. The book is about Galip’s attempt to figure out what is going on, and it combines many of Celal’s columns interspersed. This made me think a little bit of Aunt Julia and the Scriptwriters, but like Snow, what I really liked was a deep dive into Turkish everyday life and mentality.

Then, stuck in the hospital (and then at my brother’s house for recovery), I listened to Istanbul: Memories and the City (2003), Pamuk’s memoir of growing up in this metropolis. Pamuk writes a combination of travel narrative and memoir, here. I fell in love with Istanbul based on Pamuk's voice. I found his description of Istanbul's newspaper columnists fascinating. Knowing that this was one of Pamuk's fascinations helps one understand why he wrote The Black Book, which uses an eccentric newspaper columnist as one of its main characters. He revolves around the various literary portraits of the city--from 19th century Europeans, to 20th century poets, and the newspaper hacks. As a bookish guy, it felt just right. (And we readers also learn more about Pamuk’s erotic adventures as a young man than we’d want to know.)

The Museum of Innocence was a little tedious, to be honest. A young bachelor, Kemal, from a prominent family falls in love with an even younger shopgirl, Fusun. Kemal begins to assemble a museum dedicated to his passion, but it felt hard not to see this as an enormous sugar daddy fantasy.

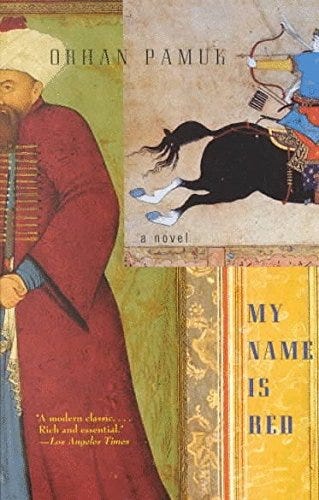

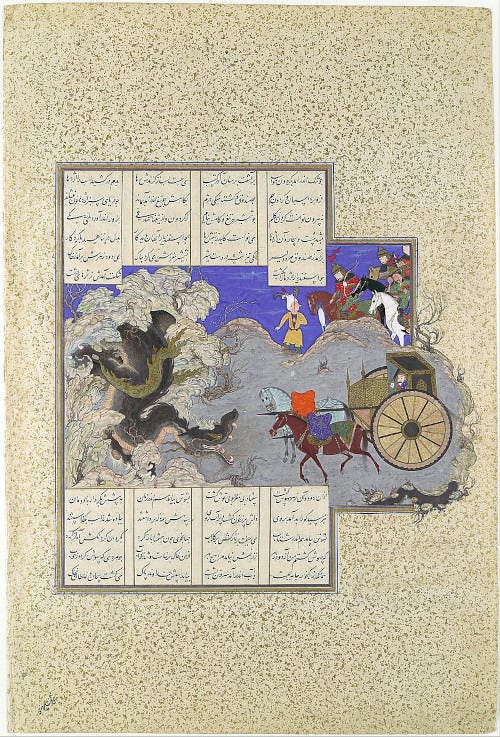

While The Black Book was an excellent contemporary urban novel, My Name Is Red is my favorite Pamuk. This is the Pamuk for people interested in visual art. (Pamuk explains in Istanbul: Memories and the City that as a teenager, he aspired to be a painter.) My Name is Red is set in a kitabkhana (a workshop for the production of illustrated manuscripts) in Ottoman Istanbul. Each chapter is narrated by a different character. The first chapter is titled “I am a corpse” and is narrated by a man who has just been murdered. (Some chapters are narrated by non-human characters: a dog, a tree, and even the color “red.”) This murder mystery provides the motive for the narrative, but My Name Is Red is really about the end of an artistic era. The time is 1591, and the painters of miniatures in Istanbul are aware of artistic developments in Venice. But also they are well aware that they are part of another artistic heritage. The book refers to masterpieces of the form of illustrated Persian books, such as the Shahnameh of Shah Tahmasp, produced in Iran shortly before the action of this novel, and given to Sultan Selim II as a coronation gift. This book is one of the masterpieces of art history, and its 259 illustrations have been dispersed among the museums of the world.

But their growing awareness of Venetian painting has made the Istanbul miniaturists a bit nervous. (When I look at artwork from later Persian or Moghul artists, I see a lot of Western-style oil paintings—portraits mostly.) Interestingly, the artist characters have a well-developed theory of art, which comes largely out of Herat, where the main Timurid kitabkhana was located. There is a conflict between East and West here, fought between the Italian Rennaisance on one hand and the art of book making as defined by Persian artists on the other. We know who won in then end.

I was recommended The Bastard of Istanbul by Elif Shafak in an article about novelists fighting for freedom, which is not exactly a good introduction to this book. The book mostly deals with the distinct ways that descendants of survivors of the Armenian genocide view their historical circumstance from the way that Turkish descendants of those do. Which sounds super boring and didactic, but the novel strikes one as a story of an odd group of characters brought together by an almost impossible set of circumstances. The book sets up a meeting between two teenaged girls, Armanoush and Asya. Armanoush is an American of Armenian heritage, involved in Armenian politics among fellow descendants of the Armenian genocide. She is somewhat anguished because her mother, following her divorce from her Armenian father married a Turkish man. She decides to confront her past by traveling to Istanbul to meet her Turkish inlaws. This already feels a little contrived, but what makes it readable is the description of Asya’s eccentric family full of aunties (even her mother is called auntie). The political aspect can be a bit heavy handed, but the characters are delightful.

The novel has it’s own amazing story. Shafak wrote The Bastard if Istanbul in English, and it was translated by novelist Aslı Biçen into Turkish and became a best-seller there. In 2006, a lawsuit was filed against Shafak by Kemal Kerinçsiz, a nationalist lawyer known for filing Article 301 lawsuits against Turkish writers. Article 301 of the Turkish Penal Code makes it a crime to insult “Turkishness”. Even though this law in on the books, the government of Turkey has not applied it. It has been applied in lawsuits by ultra-nationalists against Turkish writers who have the temerity to write about the Armenian genocide. The case was kicked out of court, fortunately.

In The Captive Mind, Czesław Miłosz explains why writers are so reluctant to leave their native land even when it has fallen to a tyranny—they are afraid to lose their readership. (If your language is Polish or Turkish, that is a reasonable fear.) Shafak, though never a political exile, found a way around the problem that Miłosz describes. But she paid for it, in a way.

I have a friend who lives in Istanbul, and I asked him about Shafak. He said he loved the book and that it was popular. About Pamuk, he said when he goes to visit fellow Istanbullu, they will have Pamuk books proudly displayed on their shelves, but the spines will be uncreased. In a way, that is the trouble with winning such a presitigious honor like the Nobel Prize. It brands you as an intellectual, which might scare off a casual reader. That’s too bad, because Pamuk is a very entertaining writer.

[Please consider supporting this publication by becoming a patron, and you can also support it by patronizing our online store. And one more way to support this work is to buy books through The Great God Pan is Dead’s bookstore. ]