The Zafarnama is a book written in 1428 by a man named Sharaf al-Din Ali Yazdi. It is a poetic biography of the bloody conqueror Timur, who had died roughly 20 years before this account was written. It was commissioned by the conqueror’s grandson, Ibrahim Sultan. The title translates as “Book of Victories.” It is of a genre known as a panegyric, which means it was written to make Timur—one of the worst humans in history—look like a “great leader.” This book, however, was extremely important to Timurid princes, and new elaborately illustrated editions were manufactured in book making workshops called kitabkhanas. I know of two biographies of Timur produced shortly after his death. The Zafarnama is not one that seems historically dependable, but it was important to the Timurids as a text that conferred legitimacy on them. And since, among Iranian and Turkic princes if medieval central Asia, elaborately produced books were highly valued, it makes sense that those Timurid princes would hire their best calligraphers and painters to make handmade editions of Zafarnama.

The Museum of Fine Arts has nine of the illustrations from a 1436 edition of the Zafarnama, which is the earliest illustrated edition that exists. While we know the name of the author and the calligrapher (Yaq’ub ibn Hasan), we don’t know the names of the artist(s).

Shah Rukh was the youngest of Timur’s sons. He would rule over part of the Timurid empire until 1447.

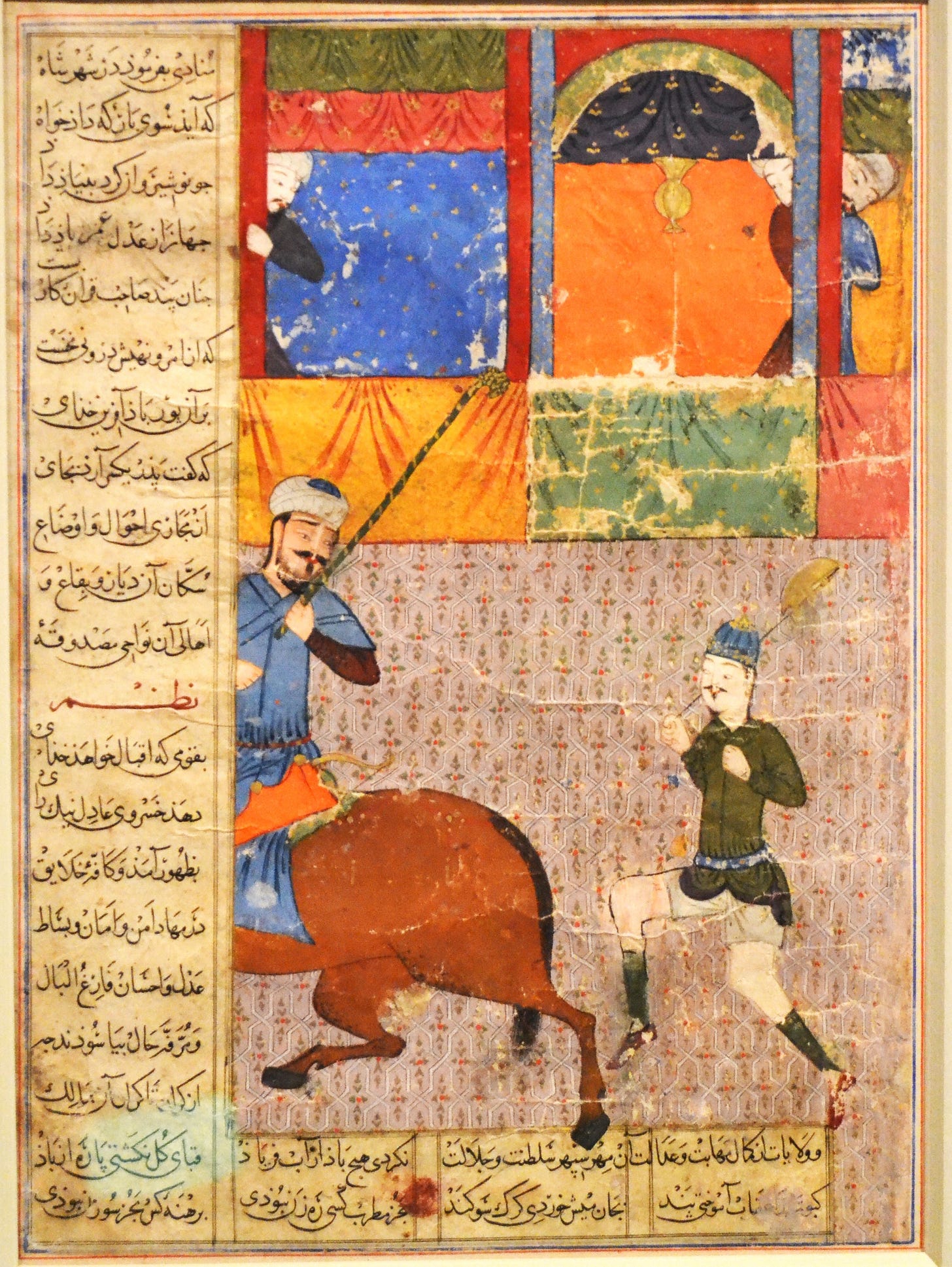

This rather jocose image of a man in white underpants prancing behind a horse is actually the left side of a two panel image. The right side, which depicts Shah Rukh mounted. That half is at the Smithsonian.

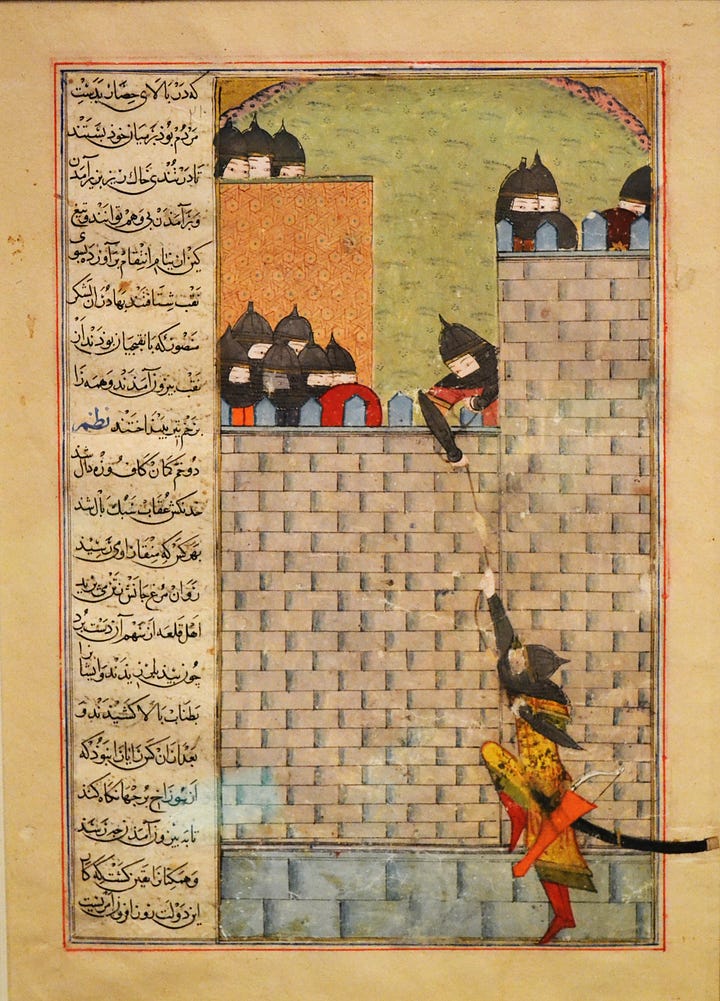

This pair is another that were meant to face each other on opposite pages. It depicts Timur’s attack of Aleppo—the right hand image shows a Mamluk soldier being helped to escape up over the walls of the city. Probably did him no good—Timur won that fight and his men raped and slaughtered thousands. Many were tied to the great mosque in the center of the city and burned alive. This is one of many cases where the Zafarnama turns an utter atrocity into just another heroic success for Timur.

Not surprisingly, there are several images of military daring.

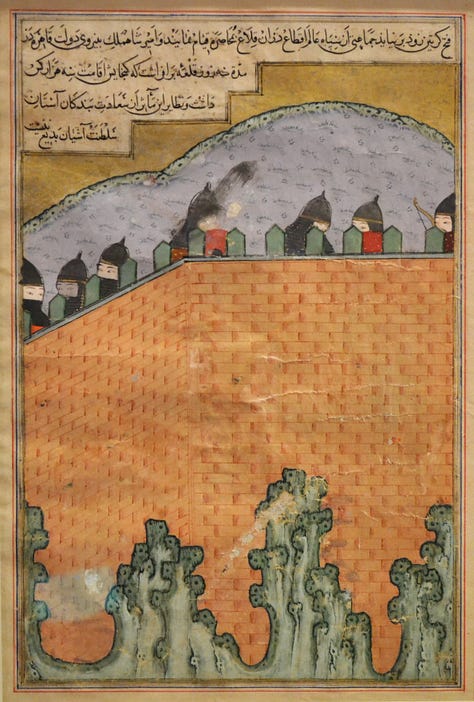

Timur destroyed the city of Baylaqaa in Azerbaijan in 1404. For some reason, presumably for diplomatic advantage, he rebuilt it, which is apparently related in the Zafarnama. What a magnanimous ruler Timur was—after he wrecked your stuff, he might fix it (if it benefited him to do so)!

It is perverse that as I look at these 600-year-old artworks meant to bestow praise and honor on Timur, a warlord who died in 1405, I am angry at the hypocrisy of Ibrahim Sultan in commissioning these artworks. I imagine there will probably be a glowing bio-pic of Donald Trump in a few years that will be the moral equivalent of the Zafarnama.

So why did I spend a few hours studying these paintings? Because even if Timur is Stalin-ish in his evil, he inspired some interesting works of art. Obviously the plays Tamburlaine parts 1 and 2 by Christopher Marlowe are fascinating examples of great art made about a terrible person. I knew the Museum of Fine Arts had some Persian miniatures on display, and after my cataract surgery, I wanted to test my new lenses on some of the tiniest artworks on display. The objects in the photograph above are all tools used in bookmaking. These are pens, brushes, and burnishers from Ottoman, Safavid (a Persian dynasty) and Qajar (a subsequent Persian dynasty) kitabkhanas. Somehow this unique edition of Zafarnama was dismembered and parceled out to museums like the Smithsonian and the Museum of Fine Arts in Houston.

[Please consider supporting this publication by becoming a patron, and you can also support it by patronizing our online store. And one more way to support this work is to buy books through The Great God Pan is Dead’s bookstore. ]