I swore I’d never look at him again,

I’d be a Sufi, deaf to sin’s temptations;

I saw my nature wouldn’t stand for it—

From now on I renounce renunciations.

The short poem above is by Jahan Malek Khatun, a woman who lived in Shiraz from about 1324 to 1382. The poem was translated by Dick Davis and comes from The Mirror of My Heart: A Thousand Years of Persian Poetry by Women. Jahan was a princess, daughter of Masud Shah, king of Shiraz and Fars from 1336 to 1339, who was murdered in 1342. Her uncle Abu Es’haq became king at that point, and Jahan was a valued member of his court. Abu Es’haq was an vigorous patron of poets, including Hafez, Persia’s best-known poet who was almost an exact contemporary of Jahan. The good life as a court favorite didn’t last—Abu Es’haq was deposed by Mobarez al-din who started a new dynasty in Iran, the Muzaffarids (who were destroyed by Timur in 1393—medieval Persia was a politically unstable place). Mobarez al-din was a religious fanatic—while he was in charge, wine and poetry were frowned upon. What happened to Jahan during the rule of Mobarez al-din is unclear (as are most of the details of her biography), but Dick Davis suggests that “her life must have been in real danger.” Going purely by what she wrote in her poems, she may have been held prisoner for a period of time and possibly exiled at some point. Mobarez al-din was overthrown after a few years by his much-less-fanatic son, Shah Shoja, who reopened the wine shops and let the poets flourish. Jahan’s life sems to have improved after this—she wrote poems praising Shah Shoja.

Jahan’s complete work consists of over 1400 poems. Two complete copies of her work survived, and weren’t published in Iran until 1995. Davis mentions this rediscovery in passing in his introduction to Faces of Love: Hafez and the Poets of Shiraz, and a larger history is implied. The rediscovery of Jahan’s poems 600 years after the poet’s death gives one hope for all the lost classics of antiquity. (I would like to know more details. I’m a sucker for a story of artistic rediscovery.)

Davis has translated a few of Jahan’s poems in each of the two books mentioned above, but the only complete version I’ve found is a self-published Divan of Jahan Malek Khatun: Persia's Great Female Sufi Poet, translated by someone named Paul Smith. Smith’s characterization of Jahan as a Sufi poet seems a little weird, given her mild mockery of Sufis in the poem above.

It is a weird fact that two of the most prominent female artists of Iran, Jahan Malek Khatun in the 14th century and Marjane Satrapi from the 21st century, are both descended from shahs. Are there any great artists descended from European royalty?

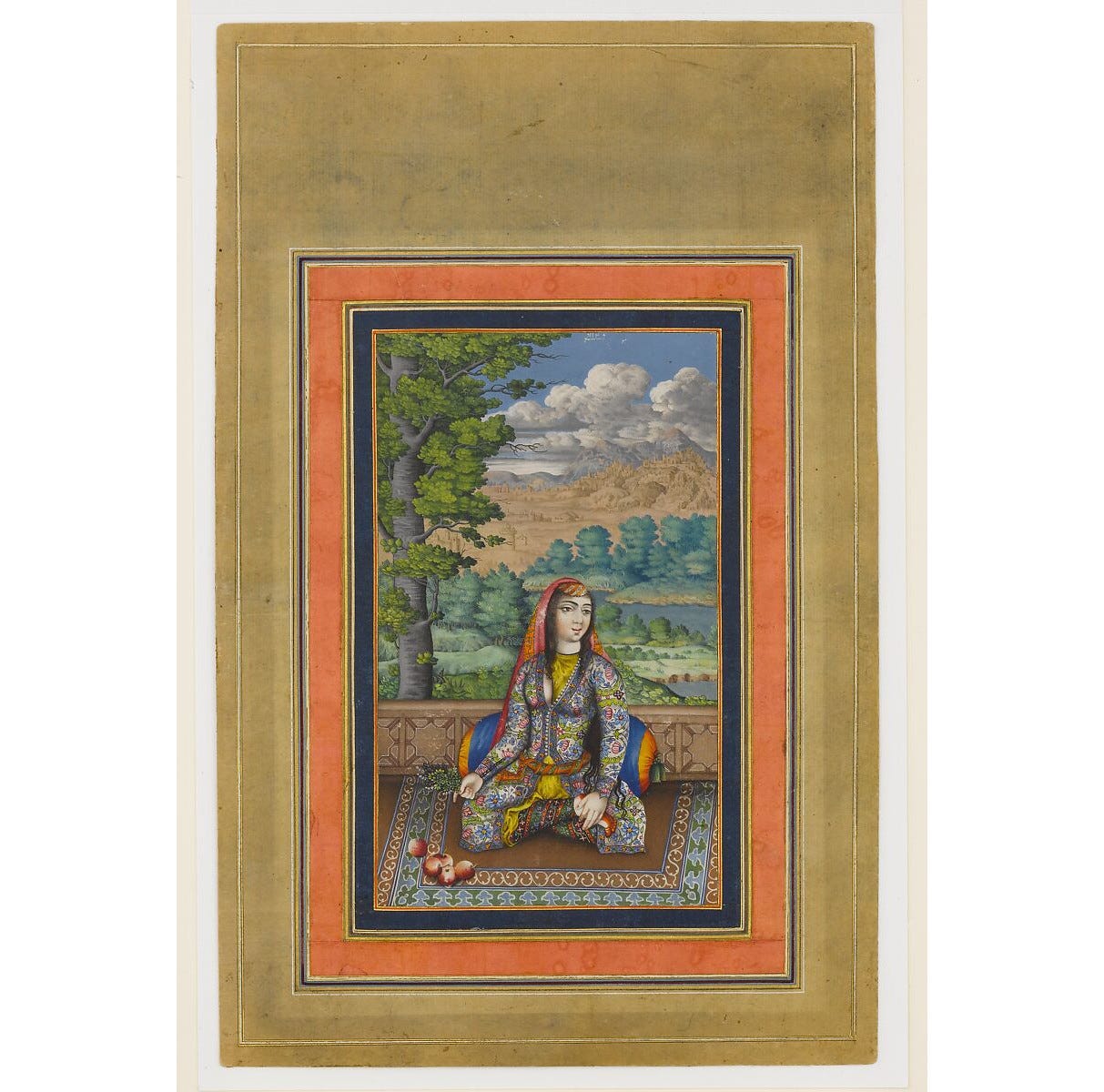

The anonymous portrait above of an elite Persian woman was produced hundreds of years after Jahan’s life. As far as I can find, there are no contemporary images of Jahan. I wonder who the first living person in Iran to have his or her portrait painted. There are pre-Islamic Persian monarchs who had their faces sculpted, but painting and drawing figures had a different meaning in medieval Iran.

Furthermore, I am of the opinion that Trump must go.

[Please consider supporting this publication by becoming a patron, and you can also support it by patronizing our online store. And one more way to support this work is to buy books through The Great God Pan is Dead’s bookstore. ]

Huzzah.

Beautiful thought maybe Barron likes wine and Poetry? Can a girl dream.

Love the piece and thanks for doing the scholarly unboxing of this lovely lovely gift!