I’ve been writing about Lawndale’s annual Big Show since 2009. I don’t really expect to be surprised by the show anymore—I usually look to see how the texture of the show evolves with each new guest curator. This year the juror was Daisy Nam, the curator of Ballroom Marfa, and what she did a little differently than previous jurors was to limit the number of pieces in the show (only 81 this year) and pick multiple selections from many of the artists. I don’t know if she was in charge of hanging the show, but whoever hung the show showed some of the artists with multiple pieces in groups of three. For instance, Chelsea Clarke’s three screenprints, Gabriel Martinez three dark quilts, Sibylle Hagmann’s three graphic paintings, and Sophia Longoria’s three spooky horizontal pieces. But they weren’t the only ones. Other artists with multiple pieces had them scattered around the gallery, like Jen Bootwala, Kamila Szczesna, and Lindy Chambers. Because Nam picked multiple pieces from so many artists, there were only 37 artists in the show (far fewer than in previous years). An exhibit like the Big Show can’t avoid being visually cacophonous, but this year’s exhibition is one of the tightest Big Shows I’ve seen.

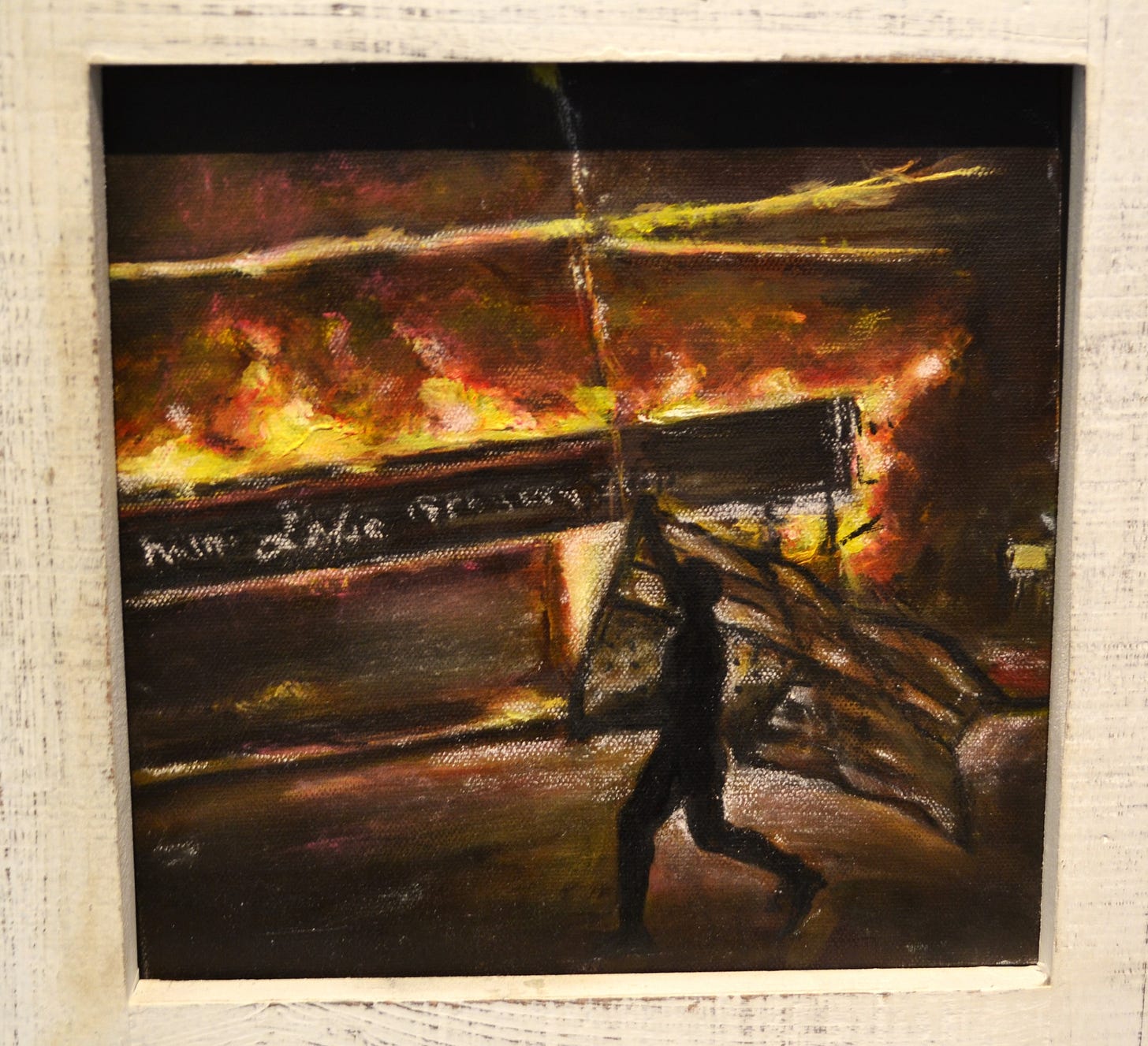

The Big Show was cancelled for obvious reasons in 2020. One of the pieces in the show is called Windows Reflection of 2020 by C.M. Lewis. It is a large group of small oil and pastel paintings on canvas, arranged within a large arrangement of window frames—three tall by six across. Each of the little paintings is a small square, bur all together it is 72” wide. Each painting shows an image that was one might associate with 2020—lots of images of COVID (hospital patients, funerals, people wearing masks, businesses closed due to COVID), images of protests and riots, and one haunting image of loneliness and isolation. The images seem fairly predictable in terms of subject matter, but Lewis’s sketchy, expressionistic painting style gives these images strength.

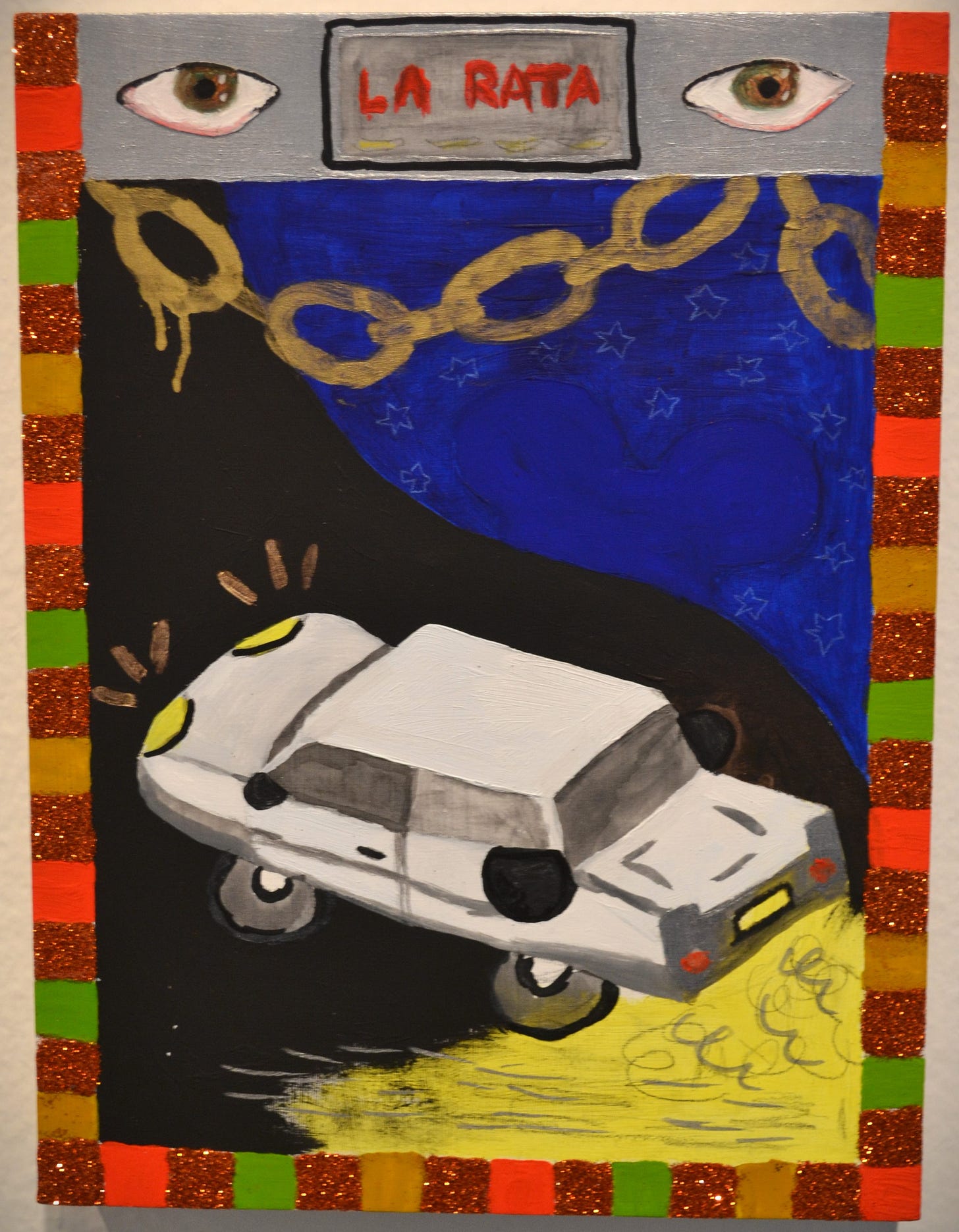

Several of the artists in the show are Open MFA members. There were three pieces by Cynthia Jamileth Giron and Jen Bootwala. One of Giron’s pieces was displayed at the Open MFA show Gathering What’s Tangible. The piece I noticed was La Rata, which amused me when I saw it at Gathering What’s Tangible and when I saw it here.

Jen Bootwala’s two pieces were knit yarn. One, Women at Work, has a political message. It has six pieces with words knit in them that hung together on one of the support beams on the ground floor gallery at Lawndale. The words read “Twice” “As” “Hard” “for” “Half” “As much”. That message seems especially ironic considering Bootwala’s means. Knitting seems to me (a man who does not know how to knit) as very labor intensive. Her other piece is also made of yarn (acrylic instead of wool) and is more abstract in design. But the name of this piece has a relationship to Bootwala’s other piece: … the labours of those vanished hands.

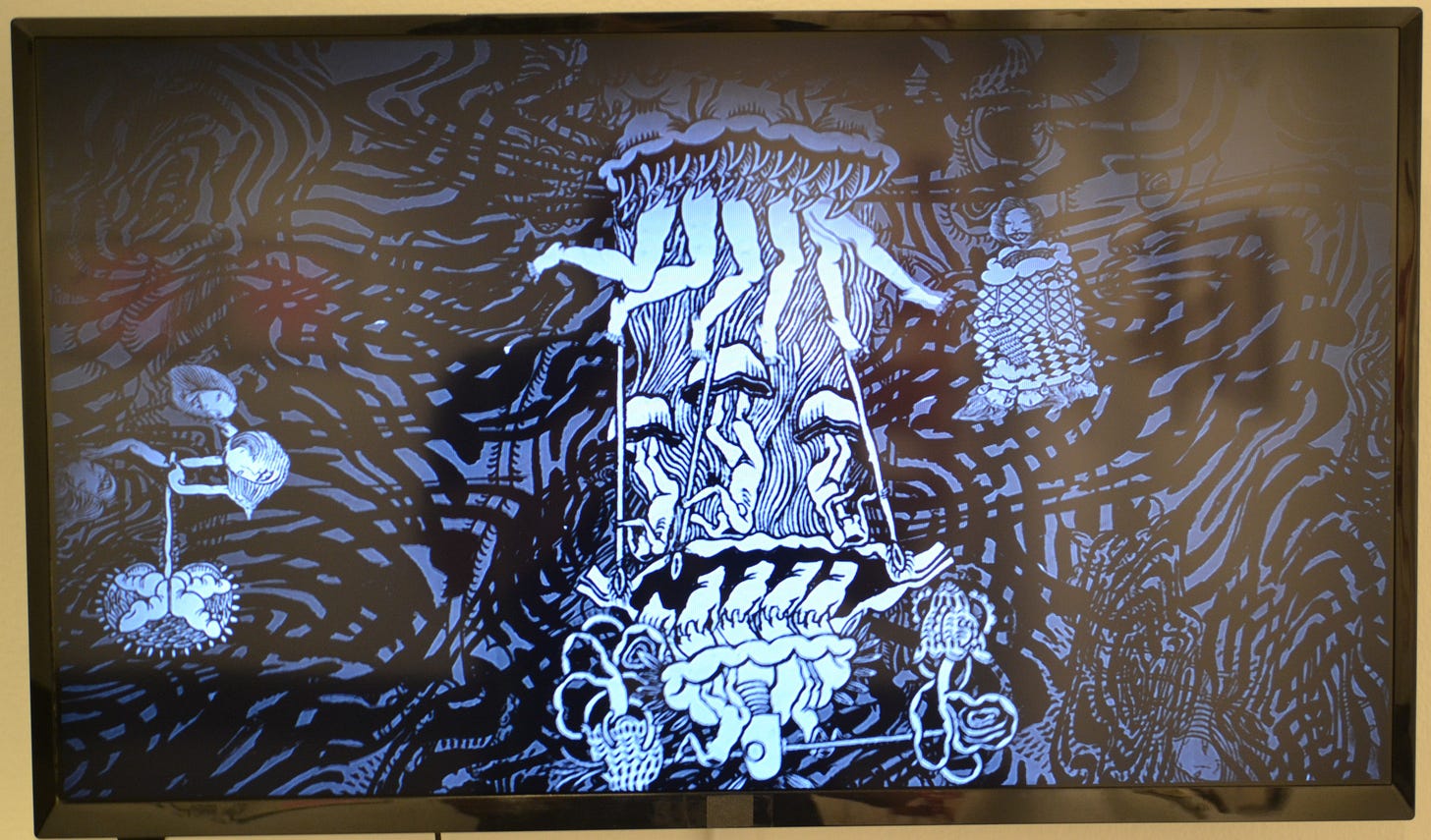

One thing I liked about the Big Show this year was how it was hung. I’ve already mentioned how some artists had their works hung together, while others did not. Also there were thematic groupings. One I observed was “ghosts” or supernatural beings. I’m thinking here of the works of Sophia Longoria and Chenlu Hou. Chenlu Hou has two drawings and an animated video in the show. Hou’s drawings (which are digital prints made from ink drawings) depict naked women with head coverings engaged in mysterious activities around what appear to be idols and a fire, with supernatural beings near them. Some of the women and idols have three breasts.

The animation, Invisibility Mimosa, is related to the drawings but is even stranger. The work has a feeling of manga pushed through a very personal lens. The overall effect is disquieting. I can’t say for certain if the figures in Hou’s drawings and animation are meant to be supernatural, but they are fantastic.

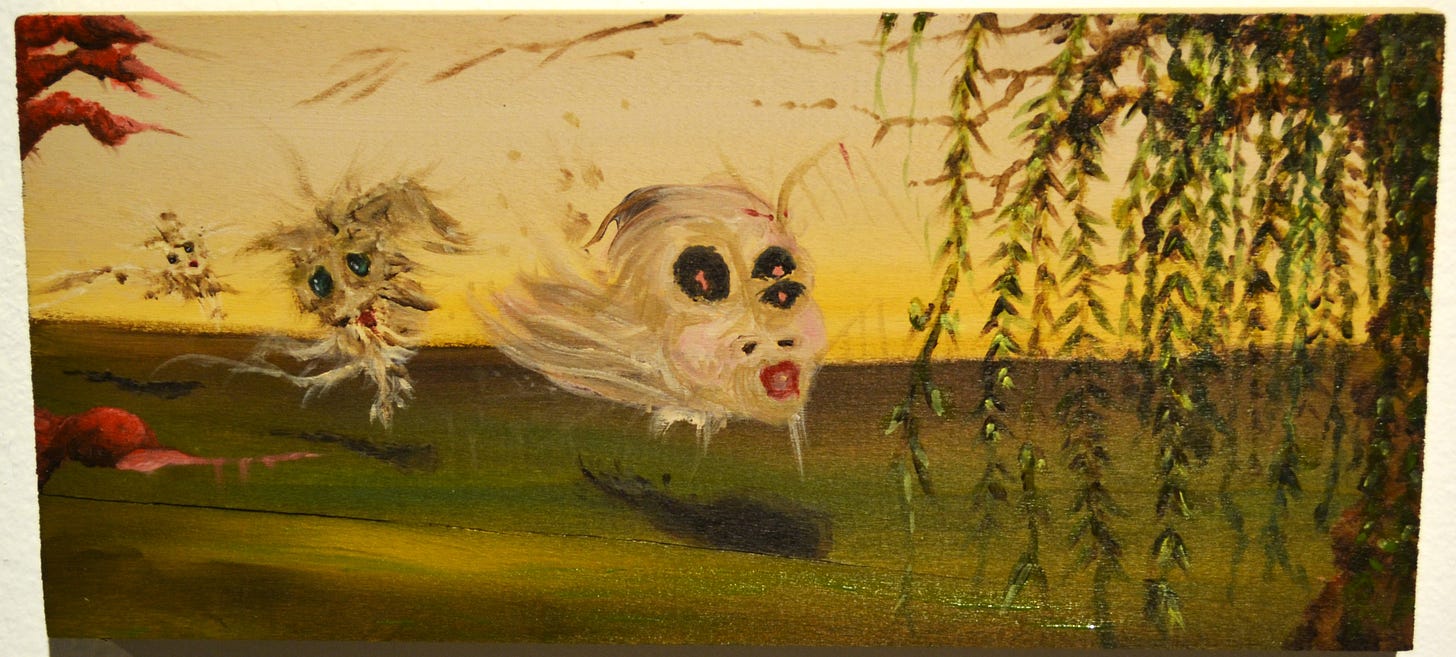

Near them are Sophia Longoria’s three paintings. They are horizontal and painted on wood slats. Each painting depicts a disembodied head floating in a landscape. They make me think of Nukekubi, a form of Yōkai, a Japanese folkloric spirit that takes the form of a disembodied head. They are small paintings and the wood slats are somewhat rough-hewn. The slat used in the painting Desert Wanderer has a section broken out it, as if it were part of an old, damaged fence before becoming a painting. Longoria’s style is loose and expressive. Longoria and Hou form a little, spooky corner in the mezzanine gallery at Lawndale, but they aren’t the only artists whose objects feel uncanny to me.

Lindy Chambers’ large brightly colored floor sculptures feel like strange, supernatural figures. They are roughly person-sized—they have the presence of a person, but the shape of a hairy, day-glo monster. The hanging hair gives them a living look, if the fluorescent colors say that this is definitely not a natural being. IU-82 has a “head” and two “arms” and looms menacingly over the viewer. If IU-82 is a body and a head, then Z-17 is just a head (like Longoria’s figures).

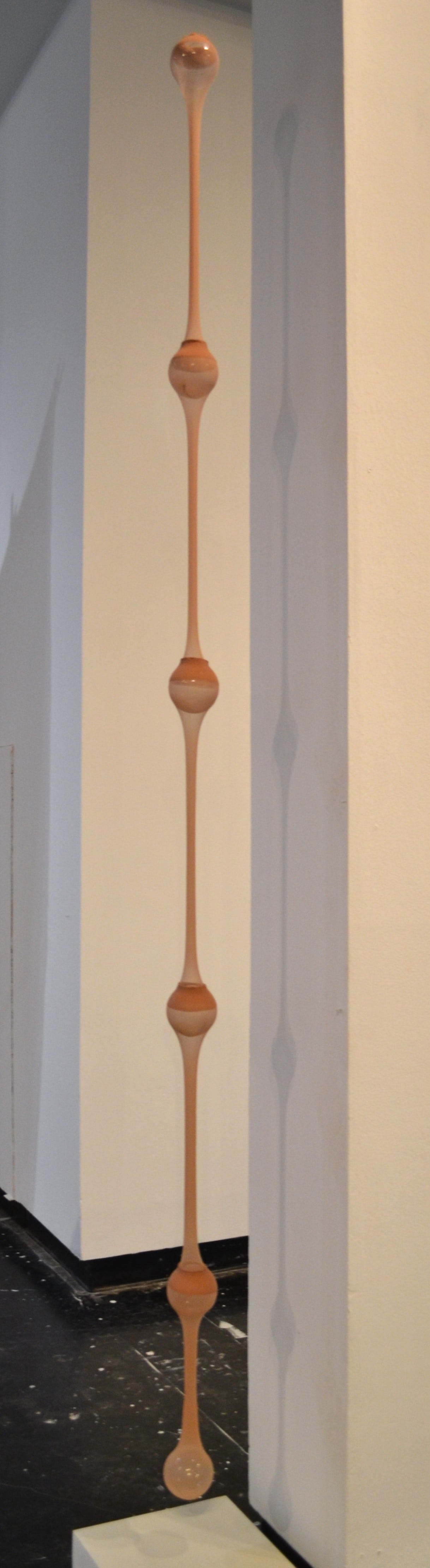

Kamila Szczesna is another of the artists whose work feels a little spooky. Her work here consists of glass balls a few inches in diameter and some flexible element. In like mother, like daughter, the flexible element are stockings, an old-fashioned item of clothing that might be worn by both a mother and a daughter. The form of the piece is six of the glass spheres spaced evenly in a vertical hanging structure between stretched out stockings. I was reminded in a way of Brancusi’s Endless Column sculptures, because one could imaging the ”column” of spheres and stockings extending upward forever, through an infinite series of mothers and daughters.

But the piece by Szczesna that struck me as ghostly was us (II). It consists of two glass spheres with a hair hanging between them. The hair is attached to something (tulle, I think) that hangs down in a parabola. From this shape, long black hair hangs down like a curtain. There is something of the lank straight black hair that reminds one of Ring, the Japanese horror film, in which those who view a cursed videotape are killed by a shambling spirit of a young girl whose face is covered by a similar veil of lank black hair. I think the disembodied aspect of Szczesna’s hair in us (II) is what is so disconcerting and creepy.

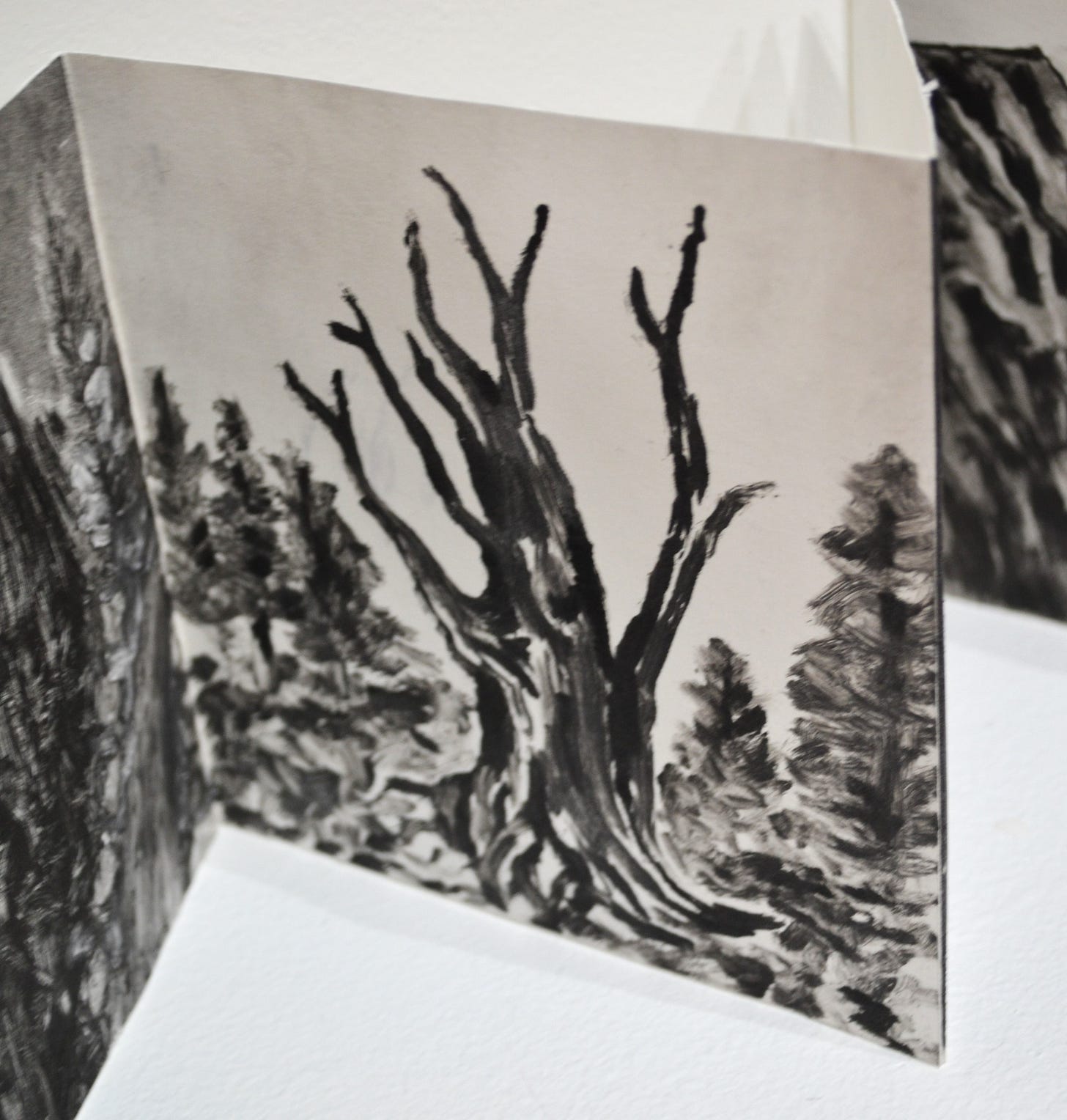

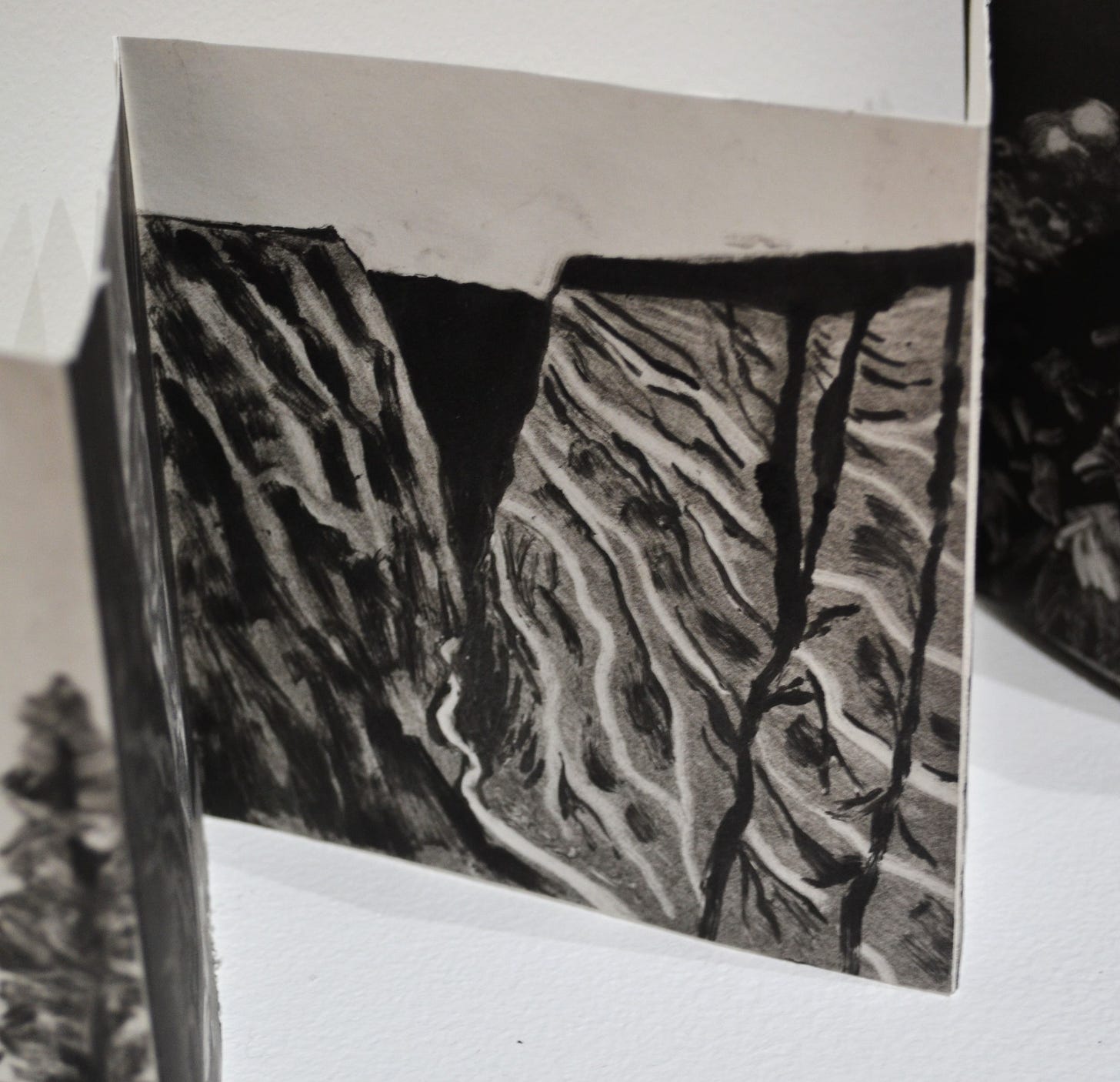

I don’t want to give the impression that the Big Show was full of uncanny objects, but I do want to mention one more that had such a vibe. Erica Reed Lee’s accordion-fold book of monoprints, Memories at a Distance, is full of disquieting images. Lee is another Open MFA participant. They depict landscapes, devoid of people. Dark, lonely and abandoned. The drawings are not polished. In some images, Lee approaches landscape in a way similar to that of Joseph Yoakum, whose drawings can be seen at the Menil through August 7th. Which is to say, Lee doesn’t attempt realism here. The landscapes are more about mood, and I read that mood as haunted.

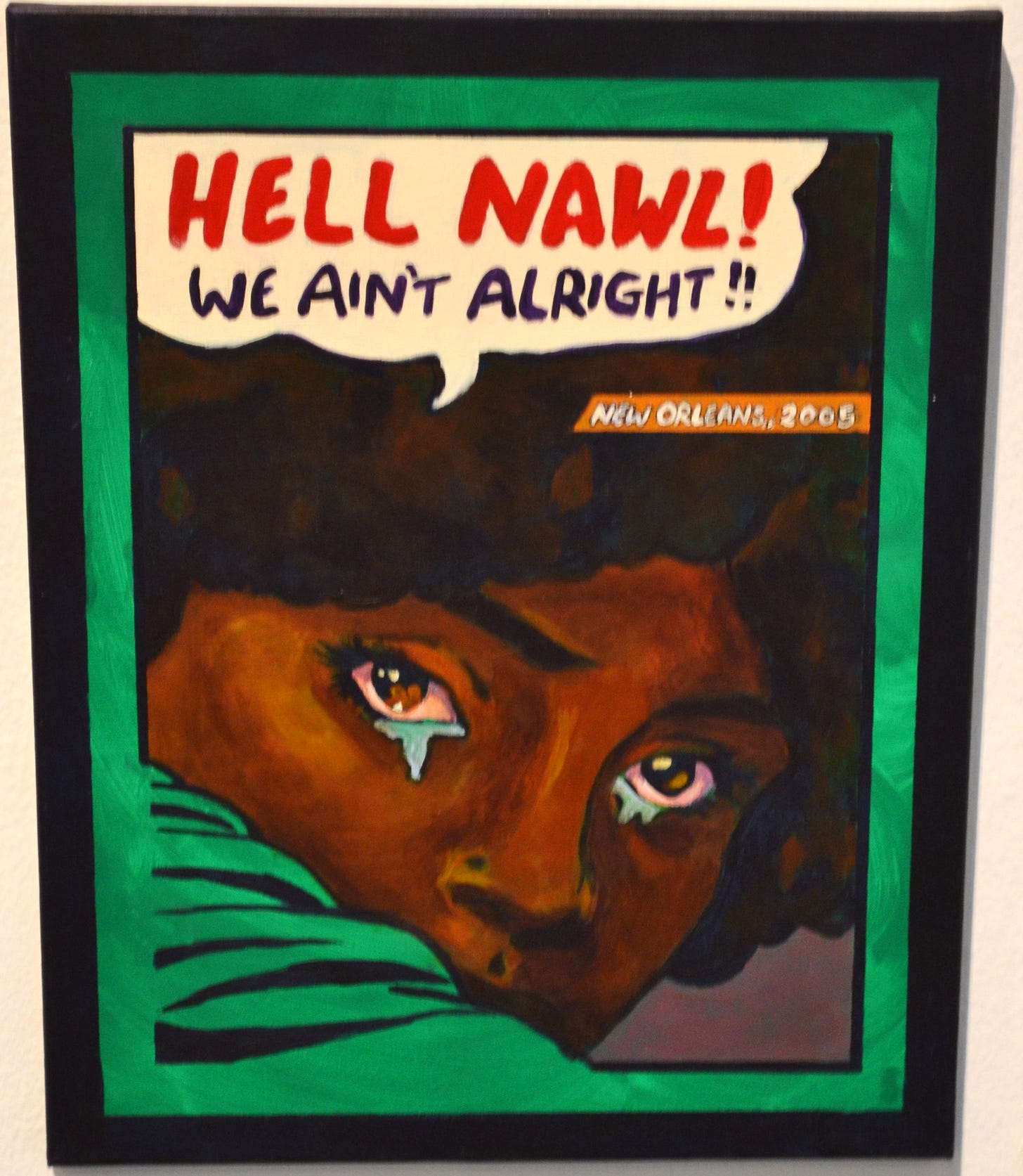

Maybe it’s a million dead Americans from Covid that makes me read so much of this exhibit as haunted by death. That seems unfair to all the other artists whose work evokes a variety of feelings other than disquiet or foreboding. Some had an explicitly political edge, like Quentin Pace’s three paintings. When the Levees Break \ Hell No, We Ain’t All Right specifically refers to hurricane Katrina. It takes the form of a painted comic panel—one could imagine it as being a tiny part of a much larger comic book. This panel is a close-up on an African-American face with tears in her eyes, saying in a word balloon, “Hell Nawl! We Ain’t Alright” with a caption reading “New Orleans, 2005”. “Nawl” could be read as an abbreviation of “Nawlins”, a local dialect version of “New Orleans”. The face in the panel is looking over her shoulder, as if she has been stopped by a journalist seeking “person on the street” reactions to the events of Katrina. Even though it is referring to an event from over 15 years ago, it has a feeling of urgency. The distress is “historical,” but it is also now.

Rontaye Butler’s piece Versuz consists of found basketball jerseys (found at a sporting goods store?) screenprinted with the words “I WANT BACK EVERYTHING THEY STOLE”. It’s not obvious to me who “They” are or what was stolen, but it does suggest something political. It could be the labor of generations of enslaved persons, it could be the land stolen by colonists or white settlers of the United States, or any number of historical injustices. (Or it could be as simple as a stolen championship title.) One imagines playing basketball against a team with such jerseys—it would be terrifying. And the title of the piece simply suggests us vs. them.

Some of the pieces seem more concerned with formal elements. Like texture, color, or design. Patrycja Adamowicz in her three-part piece The Evolution takes a series of three light tan ceramic sheets that go from more-or-less flat against to the wall to wavy and projecting from the flat wall. It may have more meaning than this to the artist, but as a viewer, it was about the transformation of these ceramic sheets from flat to undulating in space.

Sibylle Hagmann has three large gouaches with geometric designs. It appears that the board that she painted on is light tan, then each piece has one color and white gouache. The blue piece in the center of her three pieces is called Knowhow. A viewer can see the word “Know” in cursive, becoming an abstraction the way Hagmann draws it. Each of them includes a drawing of the words of their respective titles, turned into an abstract design. These three pieces could have been created using graphic design software, but Hagmann seems to have created them by hand with actual paint. But Hagmann is a designer—specifically a type designer. I wonder if Hagmann created the fonts first then painted them, or if she uses paintings to develop her fonts. (Or some combination of the two approaches.)

Gabriel Martinez’s three pieces are quilted dark blue rectangles. If you didn’t know about the origins of the pieces of fabric that Martinez uses, you could see them as formal design exercises. But as I learned when I spoke to Martinez at the time of his solo exhibit last September, the fabric is found fabric—literally found as he walks the streets of his neighborhood. So each untitled piece is not only a design, it is also a history—an unknowable history—of each piece of fabric that it was made of. And while Martinez is recalling the art of assemblage with his quilted pieces, he is also referencing a family tradition of making quilts. That’s what is difficult about formalism—it is hard to imagine a piece that only consists of its formal qualities. There is something in an artist’s personal history and development that informs they work, even if we viewers don’t really have any particular insight into what that is.

As soon as I finish writing part two of this review, I will post it. In the meantime, Get down to Lawndale and see The Big Show. It is up through mid-August.

[Please consider supporting my work by becoming a patron, and you can also support my work by patronizing my online store. And one more way to support what I do here is to buy books through my bookstore. ]

Thank you for the thoughtful response to my work! I am very excited to have the artist's book medium shown in Houston. Not enough artist's books are shared.