You are a cartoonist. You created an adventure comic aimed at young boys in 1929 and have slowly produced 17 volumes of a beloved adventure hero’s adventures. He’s had exploits on every continent, under the ocean, and even on the moon. It’s been 30 years since you created Tintin—where should you send him next? A staycation, maybe? The Castafiore Emerald is a twisty domestic comedy that marked a massive change in tone for Tintin.

Many comics are serialized literature, whether comic strips (like Dykes to Watch Out For or Terry and the Pirates) or in magazines (like Tintin or Spider-Man). If a cartoonist works on a serialized property for a long time, there is a good chance that the basic content—whether the drawing style or the mood and basic plot—will change as well. Partly this is determined by readers’ changing tastes, but often by a cartoonist’s personal evolution. When Georges Remi (aka Hergé) started drawing Tintin as a 20-year-old, he was a kid who could still be excited by a rousing Treasure Island-style adventure. But by the time he produced The Castafiore Emerald, he was an exceedingly prosperous comics tycoon. The Castafiore Emerald is a celebration of bourgeois life and manners. In short, a celebration of Hergé’s own prosperous life.

Hergé was beloved by French-speaking children all over the world. He surely knew that his millions of fans were expecting another clever adventure story for his next book, and he was certainly willing to provide it (the next two volumes of the Tintin series were straight-up adventures). But not in this volume. The setting of a country house with guests who won’t (or can’t) leave has inspired a lot of classic cinema, from The Rules of the Game to The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie; The Castafiore Emerald belongs to this genre. The country house is called Marlinspike and its owner is Captain Archibald Haddock.

Tintin is ostensibly a reporter from Belgium, although we never see him acting like a reporter—he doesn’t interview subjects, take notes, meet with an editor, or publish anything. I guess the idea of him being a reporter gives him an excuse to visit exotic foreign countries like the Soviet Union or the United States. Although his first adventure was in was in 1929, Tintin didn’t meet Captain Haddock until 1940 in The Crab With the Golden Claws. (As in a lot of serialized literature for children, Tintin doesn’t ever get older.) In The Secret of the Unicorn (1943) and its sequel, Red Rackham’s Treasure (1943), Tintin and Captain Haddock locate a pirate’s treasure which permits Haddock to acquire this stately country mansion. Tintin seems to be living at Marlinspike, one of those weird relationships between an older man an unrelated teenage boy that pop up over and over in pop culture (e.g. Batman and Robin).

With them at Marlinspike is Professor Cuthbert Calculus, a very deaf scientist and inventor who has been sharing adventures with Tintin and Captain Haddock since Red Rackham’s Treasure. As with Captain Haddock, Calculus’s actual relationship to Tintin is obscure.

The other major character is Milanese opera singer Bianca Castafiore, who has been an occasional character in Tintin albums since King Ottokar's Sceptre (1939). She is a celebrity in Tintin’s world, like Birgit Nilsson or Maria Callas. Her domineering presence, and especially her powerful singing voice, intimidate Captain Haddock. Typically she has appeared as comic relief in various Tintin adventures, but in The Castafiore Emerald, she is the main character.

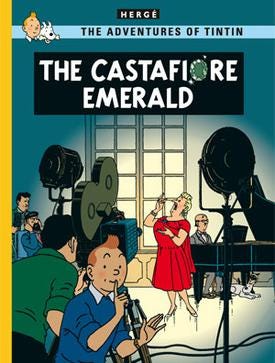

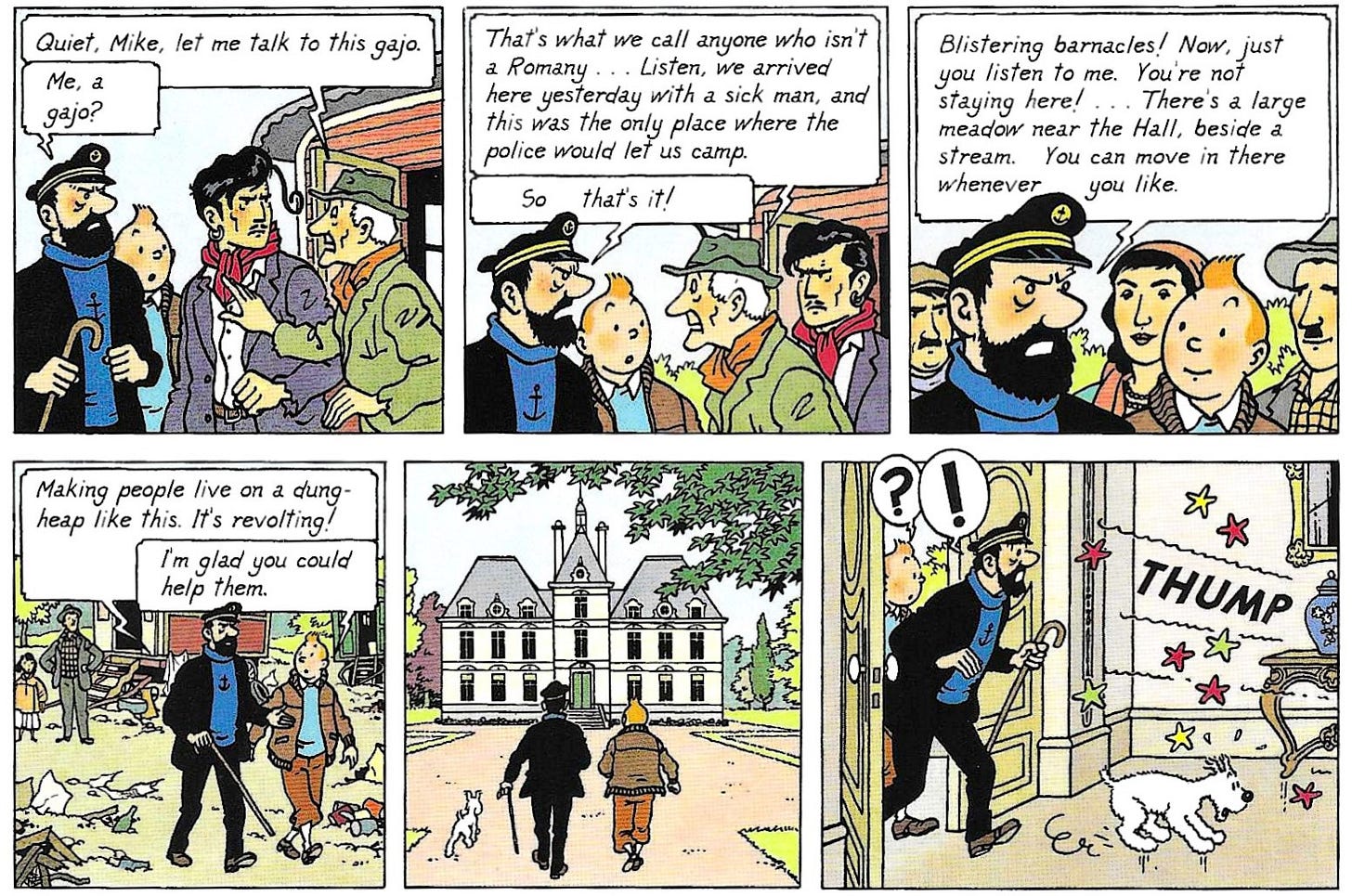

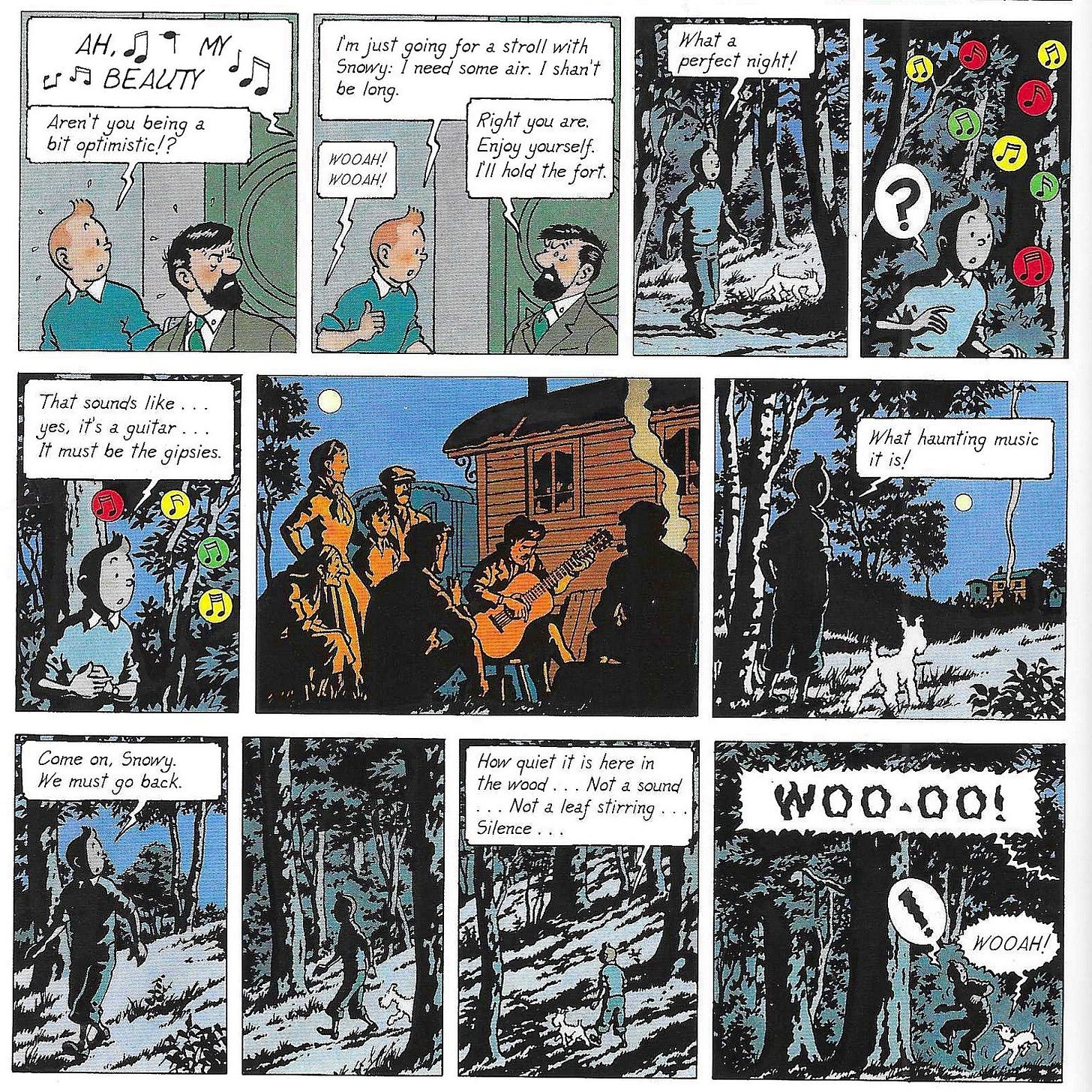

The story starts with Haddock and Tintin taking a walk and discovering a small encampment of Roma people besides a fragrant local rubbish dump. At first, they are disgusted that anyone would choose to live there, but it turns out that the Roma were forced to camp there by the local powers that be. Haddock is moved by their plight and invites them to camp at Marlinspike.

In this opening sequence, Haddock and Tintin are dressed in their customary clothes-Haddock in a blue turtleneck with a little anchor sewed on front, a black blazer and a rumpled captain’s hat. Tintin always wears a blue sweater over a white collared shirt and plus fours, a type of pants that virtually no one wears today. I wonder if French boys still wore them when The Castafiore Emerald was published (1963). These outfits have the same function as Superman’s cape or the Hulk’s torn purple trousers—they are instant visual identifiers.

Hergé was also known for his extraordinarily elegant artwork. Every figure and object is outlined with an unvarying line. In 1977, Dutch cartoonist, Joost Swarte, coined a term for Hergé’s style that has stuck: ligne claire. It implies an unweighted line, flat colors, and little if any shading. In fact, when Hergé employs shadow in his work, it stands out as a departure from his usual clean style, as in the scene below. Usually Hergé uses coloring to indicate a night scene.

Haddock receives a letter from Bianca Castafiore telling him that she is in the country for some concerts and she will stay a while with him to avoid the press. Haddock instantly starts packing to avoid her, but before he can leave, he sprains his ankle when a marble stair-step at Marlinspike breaks. So two of the inciting episodes—the Roma moving their camp onto the grounds of Marlinspike and the injury caused by a valuable bit of marble breaking, display two distinct aspects of comfortable bourgeois life: the noblesse oblige of required a propertied citizen and the dangers of owning luxurious stuff. I wonder if Hergé was thinking about himself when he conceived this.

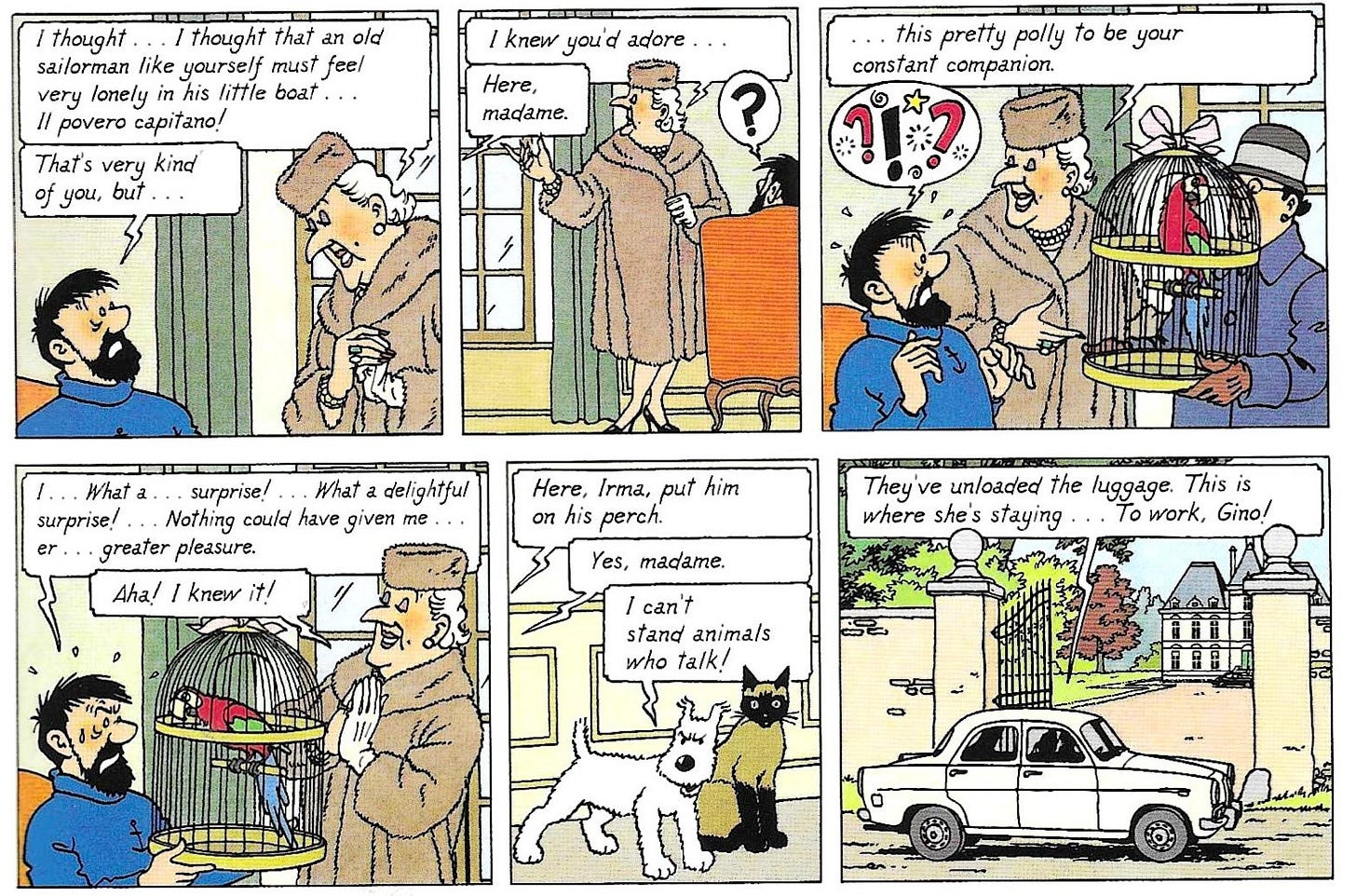

Unable to escape on foot, Haddock is trapped when Castafiore and her entourage, her accompanist Walter and maid Irma, swan in as if they had been invited. Castafiore at least provides a housewarming gift—a parrot named Iago.

The talking dog is Tintin’s companion Snowy. Even though Snowy can articulate thoughts to himself, he doesn’t communicate with the humans. Only rarely does Tintin swerve into the fantastic. While a few of the stories have a supernatural element (and they flew to the moon in the early 1950s), there are no fantastic animals, monsters, magical beings, etc.

Castafiore, like all opera singers. must practice and rehearse frequently, so her accompanist sets a piano in a spare room. This disturbs Haddock. Hergé uses a musical staff floating over a series of three rows of panels to show how the music is interrupting his life.

This sequence is also a good example of Captain Haddock’s creative cursing: “Billions of blistering blue barnacles” is a standard refrain. This phrase was invented by the talented translators of Tintin, Leslie Londale-Cooper and Michael Turner. In the original French, it is “Mille sabords!”—”a thousand portholes.”

Once he has a wheelchair and is able to flee the constant piano scales played by Wagner, the Captain retreats to his garden. But Castafiore is there talking to a pair of reporters from “Paris-Flash” who are introduced to Haddock by Castafiore. Interestingly, now that Haddock is mobile, Hergé takes the opportunity to dress him like a proper English squire.

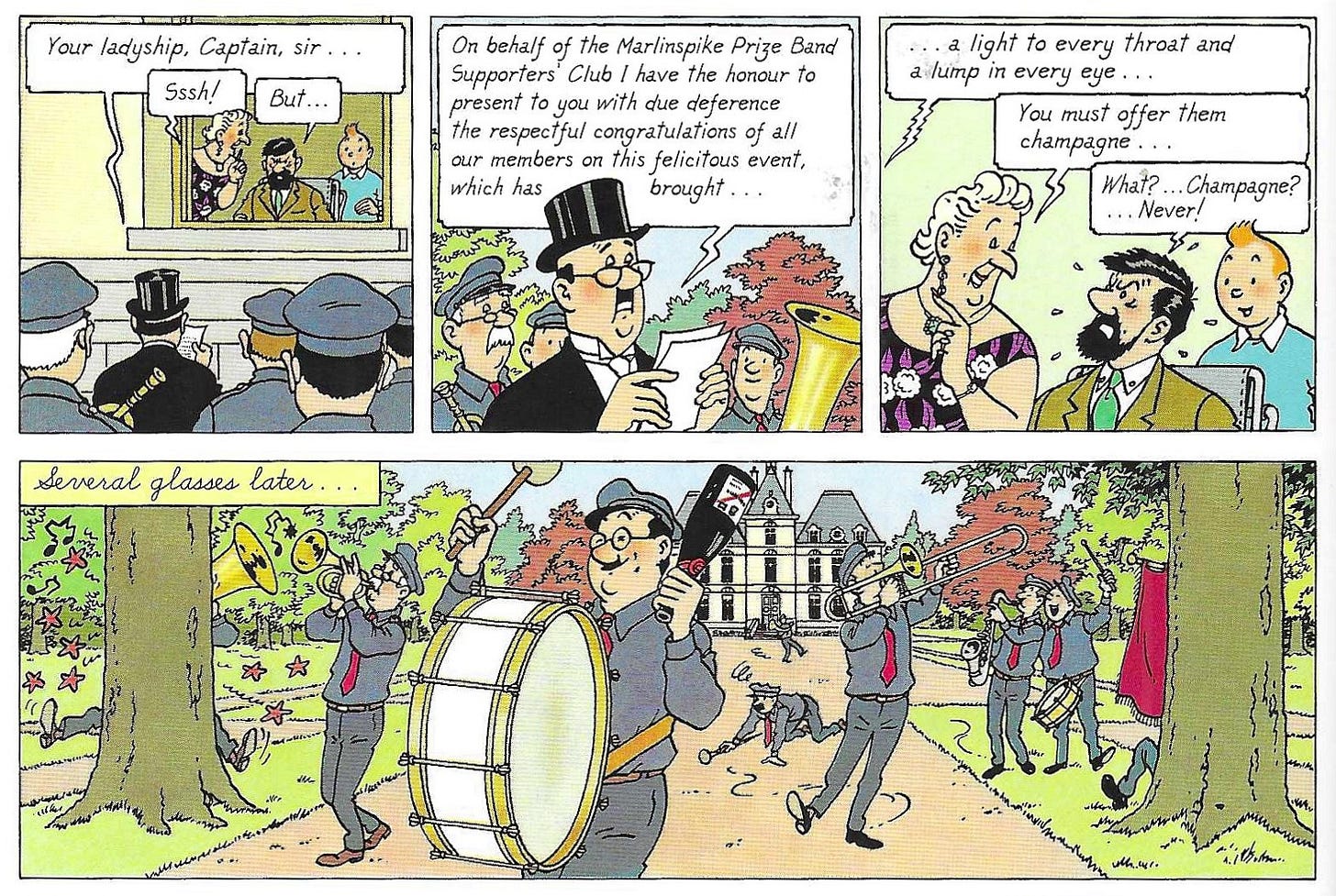

The opportunity to transform Captain Haddock from a crusty “old sea lion” (as he is referred to in the issue of Paris-Flash that announces that Castafiore’s and Haddock’s engagement) to a prosperous burgher was too good for Hergé to pass up. Tintin lives in the modern world of celebrities, gossip, and mass media. Those things don’t affect Tintin much, but the false gossip about Haddock and Castafiore’s engagement does affect other people. The local neighborhood brass band decides to serenade the couple.

In the meantime, Castafiore is paranoid about her jewels, with which she travels. Her prized possession is the titular emerald, which had been a present from the Maharajah of Gopal. The jewel goes missing of course, so it seems that this ultra-civilized domestic comedy will turn into a mystery story. That feels appropriate for Tintin—he is an adventurer, after all.

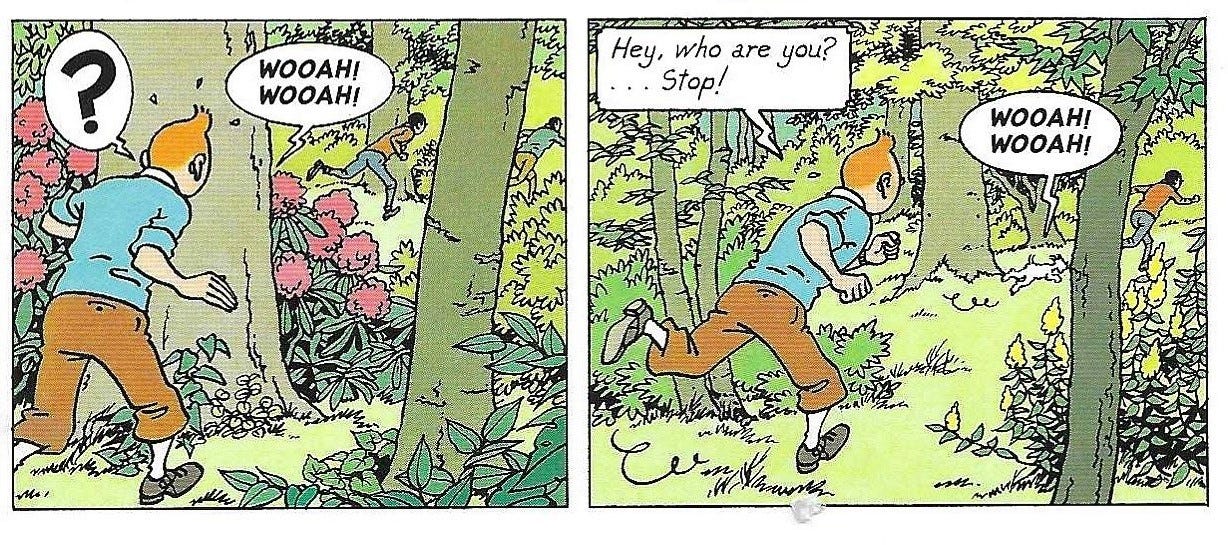

But that is a misdirection. The men Tintin is chasing above are photographers from Tempo di Roma sneaking into Marlinspike to photograph Castafiore. At every step of the story, any event that at first seems suspicious turns out to have a much less sinister explanation. After the emerald disappears, Tintin solves the mystery through his knowledge of opera—he reads a newspaper article about Castafiore’s recent performance in La Gazza Ladra, an opera whose title means “The Thieving Magpie.” The departed Roma are still suspected of theft, but Tintin deduces that a magpie stole the emerald. According to folklore, magpies are attracted to shiny things. They find a magpie’s nest and it is full of valueless shiny things—a thimble, a marble, a monocle—and Castafiore’s emerald.

Hergé was a creative and elegant artist. When Haddock is finally freed from his wheelchair, Hergé has him dancing for joy. Haddock may be, as Castafiore describes him, “a dear old sea dog, a bit crusty at first”, but Hergé draws him as being as graceful as a ballet dancer.

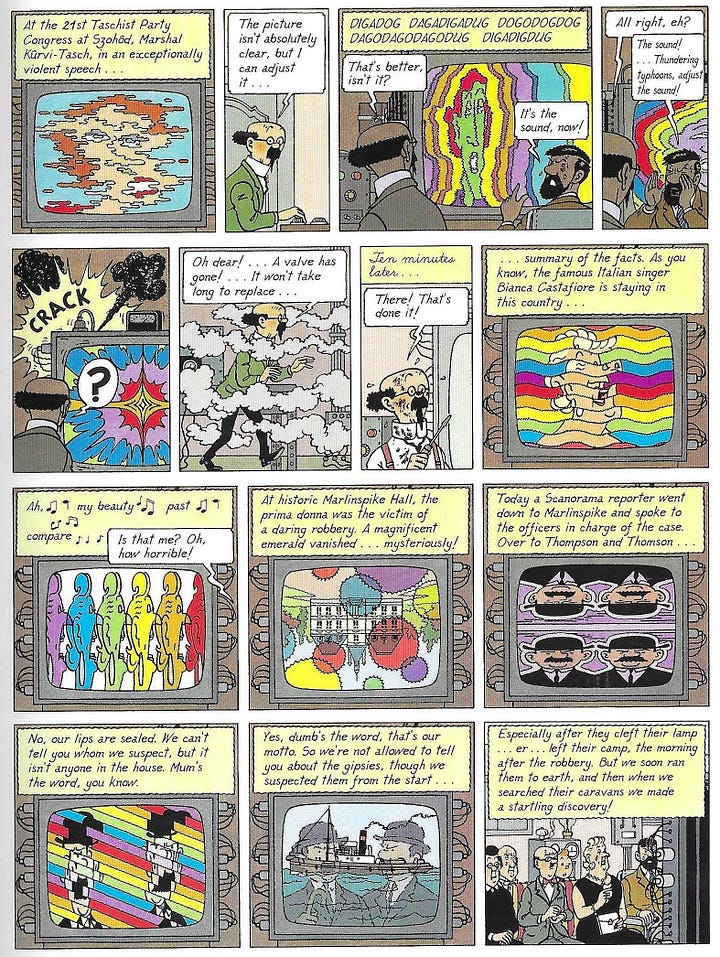

Professor Calculus is mainly used for comic relief—the joke is that he is deaf and misunderstands everything he hears. It’s a joke that gets tiring after a while, but Calculus’s scientific abilities give Hergé the opportunity to do some drawing experiments. Calculus has invented a device to turn black-and-white televisions into color televisions. It doesn’t quite work, instead showing a series of distorted images.

I’ve read that Hergé was a collector of contemporary fine art, and that all the distorted TV images are meant to represent contemporary art styles. But I can’t match any of the distorted TV images with any modern artists’ styles that I know. I wonder if Hergé ever actually intended for these images to represent modern art styles, or if this is just a fannish urban legend. But if they are art styles, it is another sign that Tintin is now well and truly bourgeois.

[Please consider supporting this publication by becoming a patron, and you can also support it by patronizing our online store. And one more way to support this work is to buy books through The Great God Pan is Dead’s bookstore. ]

I did not learn of Herge until I was in college. My son grew up reading Tintin (and Carl Barks) and has read them all a million times. It was wonderful reading those with him.

I have a very small Tintin collection and this is in it! Love it.