I’ve mentioned in recent posts the ancient art genre called “Persian miniatures”. Apparently the term “Persian miniature” was invented by Western art historians. I, who studied art history as an undergrad, have zero memory of this art being mentioned even in passing in any of my classes. So I have been trying to fill in my giant gap in my art historical knowledge.

Here is a potted history of Persian miniatures: after the Arab invasion of Sassanid Persia in the 7th century, the writing system the Iranians had developed went extinct. But over the centuries, the Iranians adopted the Arabic script (and added a few letters that they needed to properly replicate the Persian language in the new script). Once they achieved this, and once Iranians started to show political power as the first three caliphates either fell or were weakened politically, which reduced Arab political power over the Iranians. By around 1000 CE, there were Iranian poets writing epics about pre-Islamic Iran. The masterpiece in this genre is the Shahnameh by Abolqasem Ferdowsi.

The Iranians used papyrus to write on at first, but when Abbassid Caliphate fought the Tang Dynasty at the battle of Talas in 751, the Arabs captured a number of Chinese papermakers who taught the craft to the Arabs. The finest paper in medieval Central Asia was produced in Samarkand. This is what the poets wrote on, the calligraphers wrote on, and illustrators drew scenes from the poems they were illustrating.

I would love to know how the idea of books as extremely valuable objects that kings and sultans should commission them to be manufactured in superdeluxe one-of-a-kind editions came to be. Books for Iranian potentates was the same as ceilings and walls were for Italian nobles—a place to show off their “greatness” by showing off the great artists they could hire. A proper Sultan in, say, Bukhara to show that he is worthy of his rank had to hire at the very least an astronomer and a physician, but ideally should have court poets as well. It seems to have been a way for a ruler to show off his worthiness to rule. But this is speculation on my part—I don’t really know.

Then starting around 1220, the Mongols invaded and brutally conquered all of Iran, Initially the Mongols were mostly pagan, but the contingent that conquered and ruled Iran, known as the Ilkhanate, converted to Islam. By the 1330s, the Ilkhanate was in deep political trouble, and perhaps as a way of demonstrating the Mongols’ adopted Persian character, they produced what in now known as the Great Mongol Shahnameh. This is a fairly early example of the art of Persian miniatures, but there had been earlier books with fantastic scientific and historical illustrations. But the Mongols brought something to the artform—they showed the Iranians Chinese art. The plants and landscapes and female figures in Persian miniatures show a distinct Chinese influence.

As the Ilkahnate slowly fell apart, Timur and his gang of mauraders set up a shortlived Turco-Mogolian empire that loved to produce very fancy books. They set up a large bookmaking workshop in Herat that produced many key works. Herat was the Florence of 14th century Iran. At this point, we start to learn the names of several masters of the art.

The art of book-making was successfully practiced all throughout the Muslim world. The Ottomans had their own large book-making workshop in Istanbul (as described in My Name Is Red) , the Iranians had such workshops in several cities—some run by local potentates, and some (in Shiraz) as a private businesses taking commissions—and the Mughal empire in India had bookmaking workshops.

These books were completely handmade, and there were different specialists who worked on separate parts of a book. The calligraphers and painters did most of the work we see, but there were specialists in applying gold and silver leaf and trim to the pages, embossers to work on the covers, book binders to put the whole thing together. But like many artforms, technology pretty much killed this tradition. Once goods from factories started pouring into these countries, funding a workshop full of book artists maybe stopped being so prestigious. If you were Indian royalty, you would rather buy a custom-made gold-plated Rolls Royce than a hand-made book illustrating a 1000-year-old poem.

But like many artistic practices that are obviated by technology, some practitioners continued the tradition outside of established book-making ateliers. When the book workshops disappeared, the official value of this art disappeared. But the tradition was carried on by individual masters. You can find many videos of modern miniature masters practicing their art

In an article in The New Yorker, “How Shahzia Sikander Remade the Art of Miniature Painting” by Naib Mian, she writes about the attitudes toward miniature painting even in Central Asian art schools.

By the time the artist Shahzia Sikander arrived at the National College of Arts, in 1987, manuscript painting was seen as kitsch. But, on campus, Sikander was introduced to Bashir Ahmed, one of the few artists linked to the craft’s legacy. Ahmed had studied with Sheikh Shuja Ullah, the last in a family of Mughal court artists, and, in 1982, he had founded a two-year program in miniature painting, the first of its kind. Many saw Ahmed as an outré traditionalist, but Sikander sensed an opportunity to explore—and remake—a form ignored by the art world.

The National College of Arts is an art school in Pakistan. And Shahzia Sikander is an artist whose sculpture, Witness, part of an installation called Havah… to breathe, air, life, was damaged by an unknown religious fanatic on July 8. Sikander is at this point in her career an art star, but early in her life as an artist, Sikander spent a lot of time in Houston. Sikander lived here in the late 90s—she was in the CORE program.

Sikander has had several solo exhibits in Houston—two at the same time as her CORE residency at Barbara Davis Gallery and Project Row Houses, and more recently, a big traveling exhibit called Shahzia Sikander: Extraordinary Realities that was at the Museum of Fine Arts in 2022. I saw it then and liked it, but I didn’t know of her connection to Houston at the time.

It turns out that there is a permanent Shahzia Sikander a few blocks from where I live in Midtown. At the corner of McGowan and Main, there is a plaza that is considered part of Midtown Park. It feels more like part of the adjacent apartment complex. But it is a pleasant little plaza, and the trees they planted when they built it are surprisingly large. Sikander’s piece is a circular fountain with a tilted circular form projecting up from the fountain at an angle. On the top of this circle is a mosaic of a man’s face, while along the sides of the circle are plant mosaics. It is called Mary-Am.

I have no idea whose face is depicted on the tilted circular element.

In February, a new temporary installation by Sikander was erected on UH Campus. Havah…to breathe, air, life consists of two parts: a monumental sculpture called Witness and a video called Reckoning. On July 8, as hurricane Beryl was rolling into Houston, Witness was vandalized in a disturbing manner—the female figure was beheaded.

Havah…to breathe, air, life was initially installed in Madison Square Park in New York City, before being installed here. It was always intended to have a political message. Sikanker said that it was a response to the roll-back of abortion rights in the US. The figure in the center wore a lace collar reminiscent of the collar worn by Ruth Bader Ginsberg on the Supreme Court. The woman’s hair is in a spiral braids that looks a little like a ram’s horns.

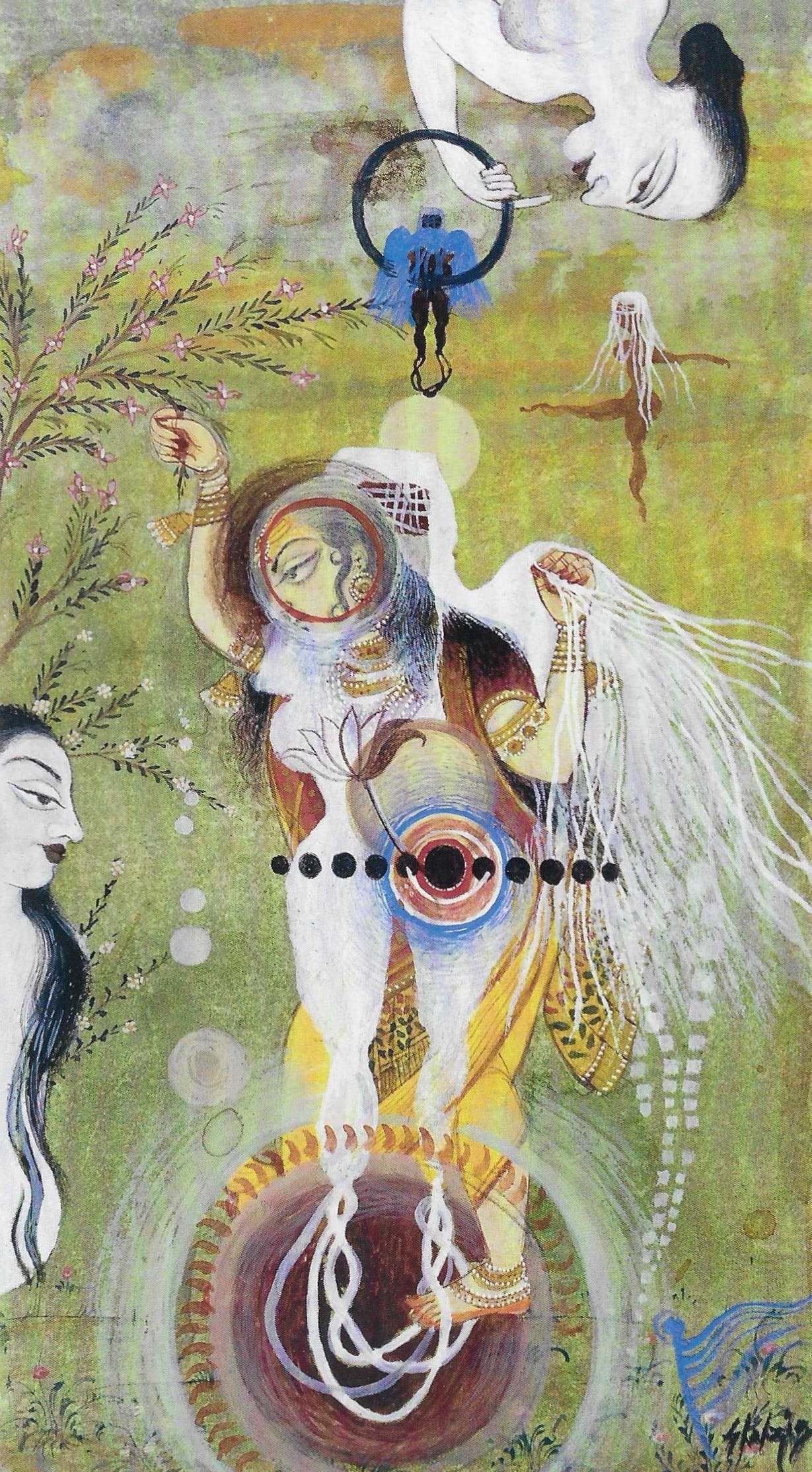

The woman with ram’s horns is an image Sikander has employed before. In 2001, she made a painting called Pleasure Pillars at the center of which was a woman’s face starring straight at the viewer with spiral “horns” on either side of her face. It is a striking image but became especially memorable to me because it was used to illustrate Sikander’s New Yorker profile. But it must mean something important to Sikander—she reused the horn headed woman in Witness.

Texas has a bunch of the most hateful, anti-woman religious fanatics in the country. One cell of these hateful losers is Texas Right to Life, which instantly protested the erection of Witness at UH. They released a statement opposing Witness on February 7, calling it “satanic” and a “statue honoring child sacrifice”. There were protesters with signs, a petition—in short, the civil ways we have to protest things. I disagree with them because they are morally wrong, but I’m all for non-violent protests.

But destroying an artwork is a step too far. This act reminded me a little of the destruction of the the Buddhas by the Taliban at Bamiyan. The Taliban show us that what will be done to artworks will eventually be done to people. My assumption when I see artworks destroyed by political fanatics is that it is just practice for genocide. The UH security cameras caught the destruction on film, so I assume the culprit will be caught. He picked a good time to commit his deed—he went there just as Beryl was rolling in. The campus was largely deserted.

The weather gives the deed a somewhat apocalyptic look. It feels appropriate.

[Please consider supporting this publication by becoming a patron, and you can also support it by patronizing our online store. And one more way to support this work is to buy books through The Great God Pan is Dead’s bookstore. ]