Back in the early 90s, the staff The Comics Journal became aware of a Malaysian cartoonist named Lat. His graphic novels Town Boy and Kampung Boy intrigued us. One of the benefits of working for The Comics Journal was that we often heard about interesting foreign comics a few minutes before the rest of America did. I found a copy of a Malaysian edition of Town Boy at my favorite used book store, Half Price Books and Records. I mentioned my find to Jim Woodring, and he replied that he couldn’t understand someone ever selling their copy. Lat, if you ever read this post—know that this is high praise indeed.

Lat is the pen name of Mohammad Nor bin Mohammad Khalid. He was born in 1951 in a rural village (which are called “kampungs”). When he was 11 his family moved to Ipoh, a medium-sized mining town. That transition, from rural child to city teen, is the subject of Town Boy, an autobiographical book published in 1981.

Lat and his family moved to Ipoh when they were given housing through a “Cheap Housing Scheme.” I like this detail—right at the beginning of what we will soon see is a classic coming of age story, we learn that Lat’s life was transformed because a very new nation (Malaysia gained independence from Great Britain in 1957) wanted to move its rural population into cities. Lat’s life as a journalist and cartoonist is a result of a modernization program by the Malaysian government.

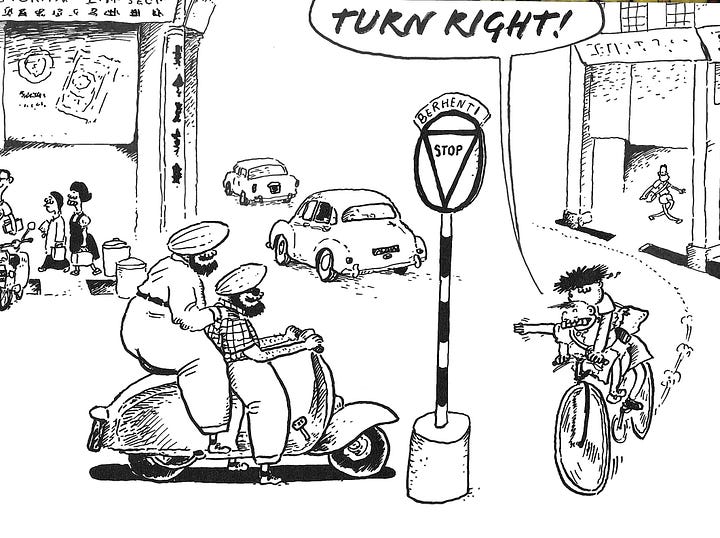

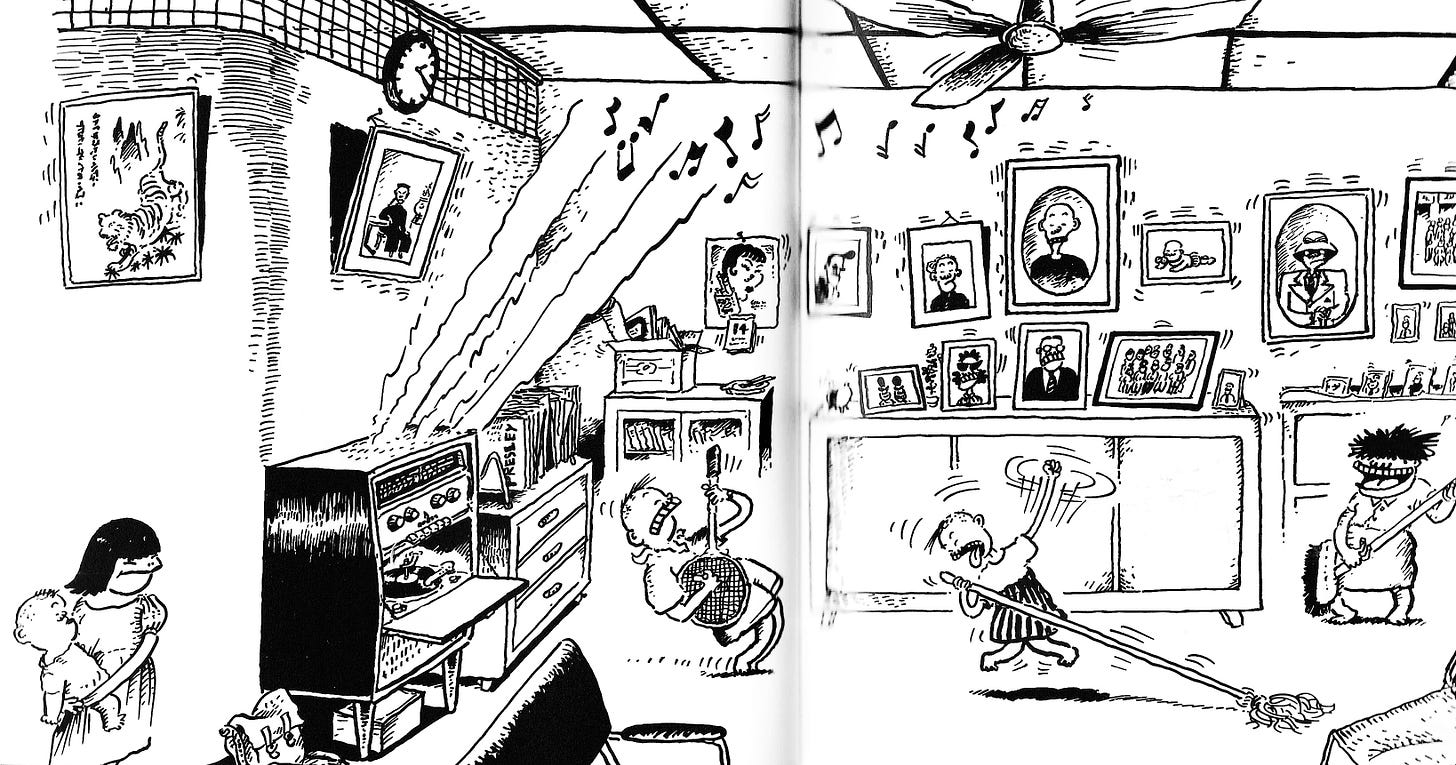

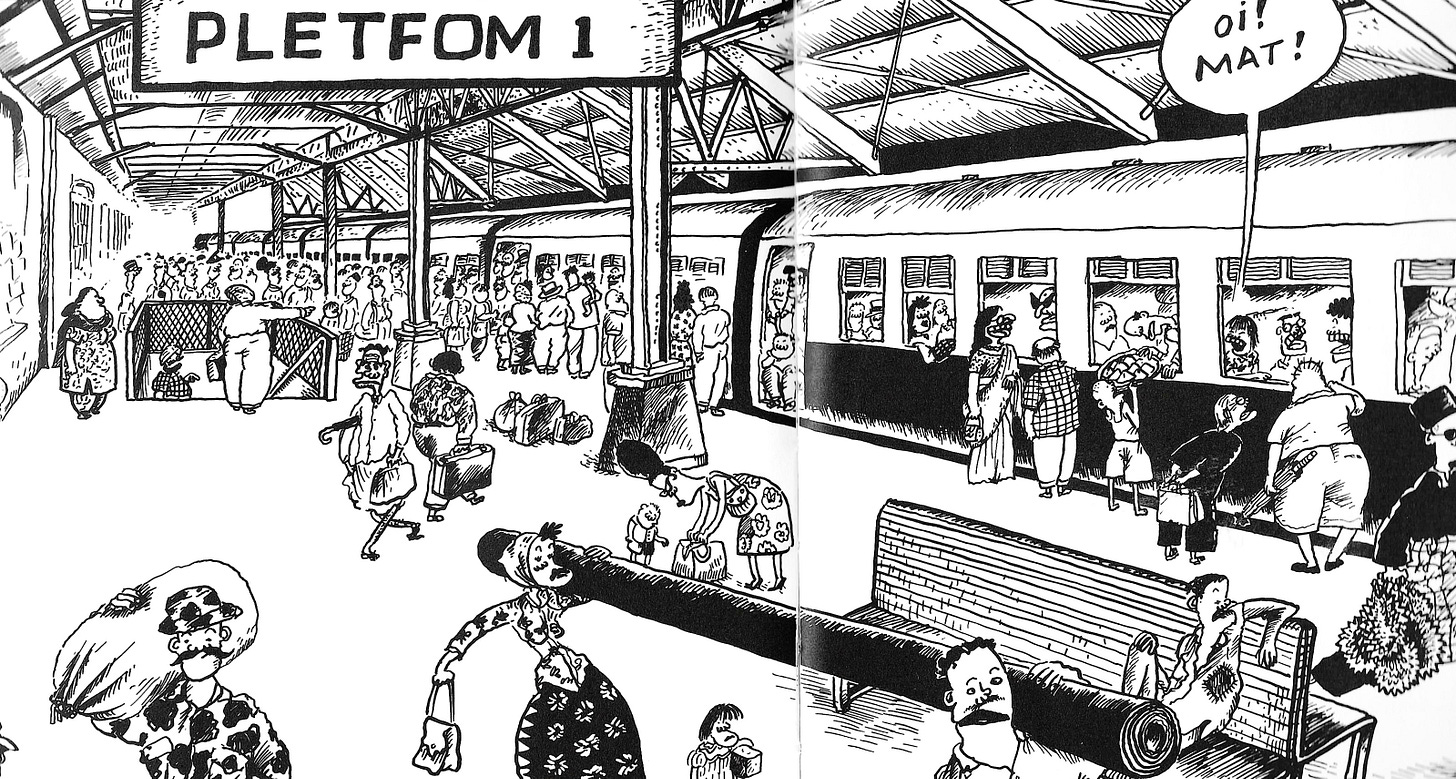

The first thing Lat noticed is how different the hustle and bustle of city life are compared to life in a kampung. Lat biked to his new school where he was accosted by another boy, a “rather typical Chinese fellow you’d see anywhere.” This was Frankie, who would go on to be Lat’s bosom buddy for the remainder of their childhood. They bonded over the fact that Frankie knew a lot about pop music and owned a record player.

Lat is the boy with the bushy black mop on the right. Lat’s drawings are bursting with energy. His style is cartoony, never slick. You see Lat’s hand in every quavery line. I have a theory that cartoonists who come out of the world of animation, like Carl Barks or Walt Kelly, have a more highly polished line—which can be appealing. But there is something vigorous and personal about Lat’s relatively unpolished drawing style.

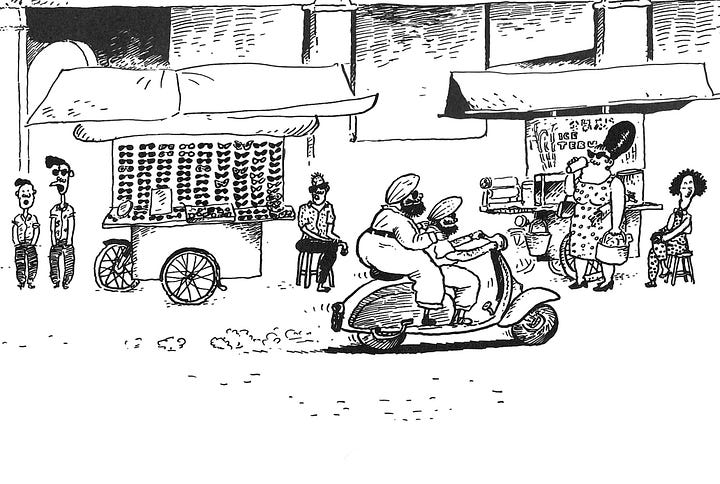

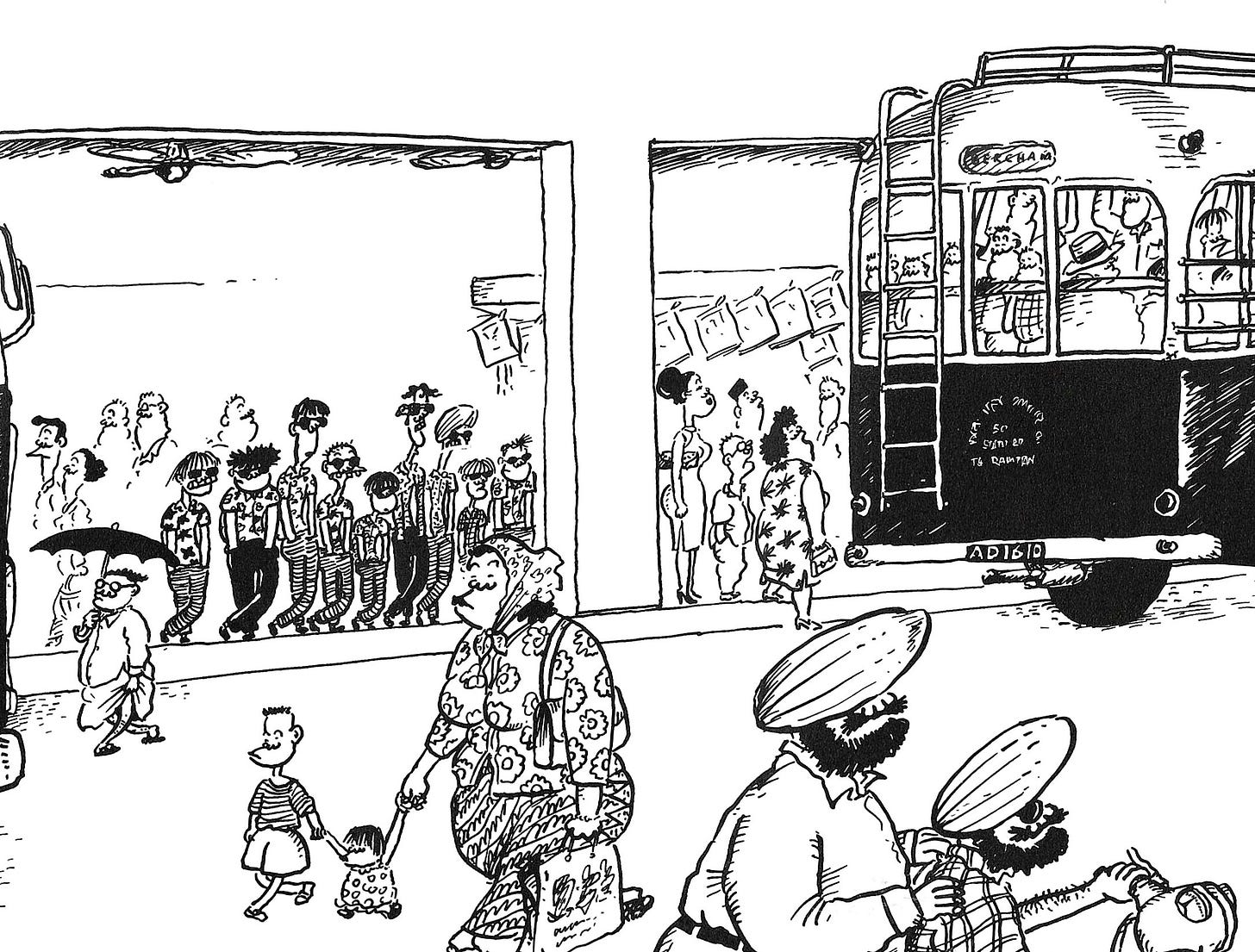

Lat depicts Ipoh as a bustling place full of street life. One detail he pops in several times over the course of the book are a pair of turban-wearing men riding a motor-scooter.

Interestingly, these two guys show up at various points in Lat’s life, seemingly riding the same scooter over a period of many years. Even though they play no part in Lat’s story, they simultaneously represent the bubbling stew that was city life and the continuity of that life over the years of Lat’s childhood. Ipoh isn’t changing—Lat is.

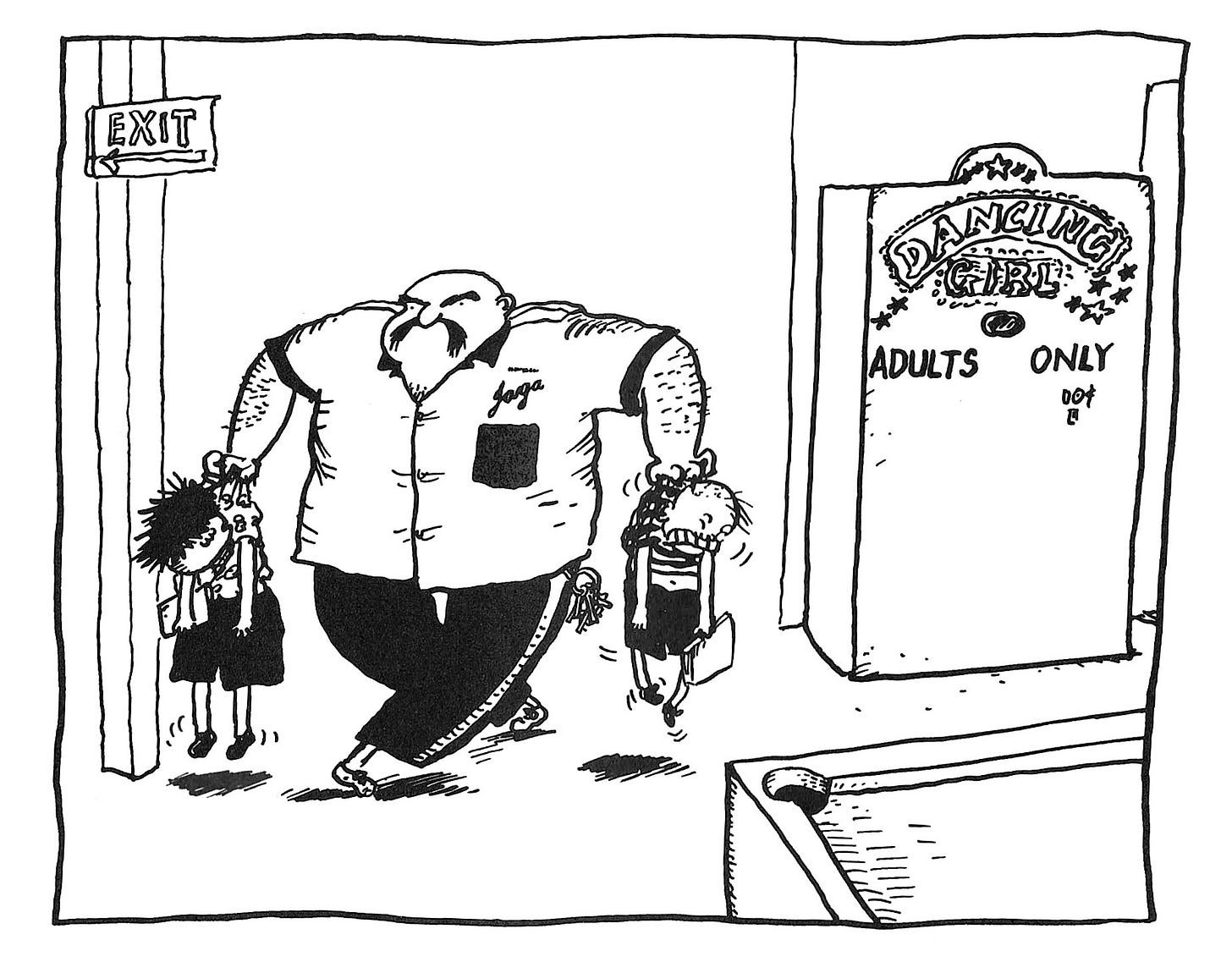

Lat and Frankie get up to somewhat universal boyhood shenanigans. They cheated in a footrace at school (and were caught together); they sneaked in to watch a peep show (and were caught together). They were best friends, but they were separated in school. Frankie was a smart kid and Lat was “not dramatically above normal, actually. . .”

But as they became teenagers, they made friends with a gang of fellow boys. Their main activity? Hanging out together in public.

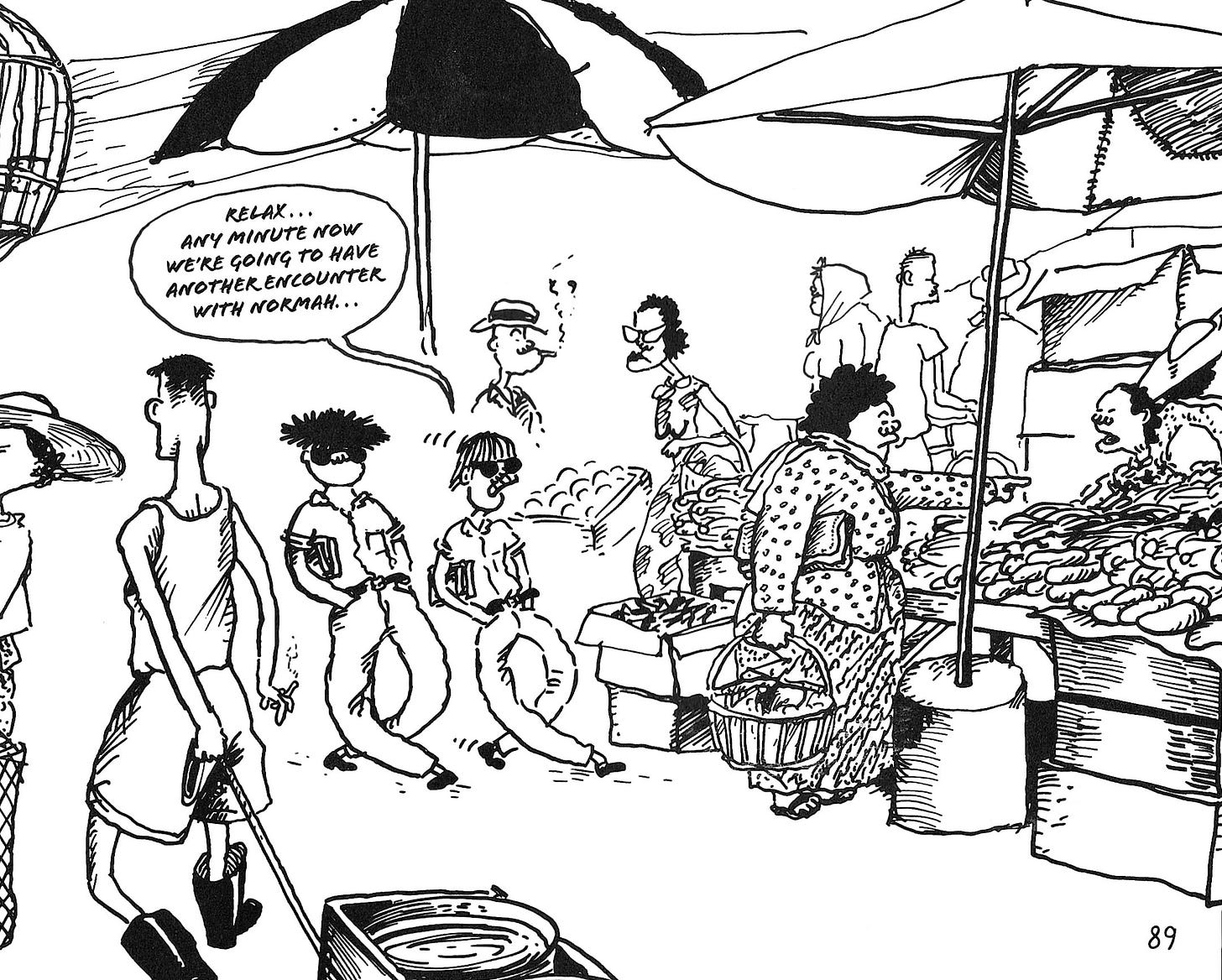

Lat depicts them as having a slouching affect that seems to be universal among teenage boys, whether in 1960s Malaysia or 2020s America. (I was a13-year-old idler haunting Memorial City Mall in the mid-70s.) There is a time of your life when wearing sunglasses was a sign of “coolness” (if only in your own mind). But that is also when the hormones start flowing. Lat, Frankie, and the boys were obsessed with a local girl named Normah.

Lat, known for being a good artist, was asked by Normah to look at her drawings. They met in a cafe, and were observed by Frankie and the boys. The boys were envious and curious about Lat and Normah’s status. “Is she going to be your steady?”

Because Lat and Frankie were tracked differently in school, they had different educational destinations. Frankie would be studying in the UK for his A-levels, a educational standard that exists in the UK and in many Commonwealth countries that you have to complete before going to a university. Lat stayed home. Their last meeting has each wishing each other well—Frankie was constantly encouraging Lat to follow his artistic leanings (which he did).

A lot of comics depict teen life—from Harold Teen to Archie to Heartstopper. Teens have historically been some of the main readers of comics. Teen life is a universal subject. Town Boy is maybe my favorite comic about being a teenager.

A quick reminder: I am writing this series about important (to me) comics to psyche myself up for Comics Sans Frontières, the comics conference being held on the campus of Rice University in late March of this year. I hope to see some The Great God Pan is Dead readers there!

[Please consider supporting this publication by becoming a patron, and you can also support it by patronizing our online store. And one more way to support this work is to buy books through The Great God Pan is Dead’s bookstore. ]

Helena recommended this to me, though I faintly recall it back when it was published here. I’m looking forward to reading it—and your comic reviews!

I enjoyed the 2 Lat books published here. I sold them to make room for new books, though, so Jim Woodring would be disappointed in me! Reading your article puts me in the mood to re-read them, though, so maybe I will buy them again (a terrible thing I do - sell, re-buy, sell, etc.) or maybe check the library.