Over the weekend of March 20 - 23, Rice University in Houston, Texas, hosted a tiny academic conference dedicated to comics called Comics Sans Frontières. The prime mover was Christopher Sperandio, an art professor at Rice who has been extremely active in promoting the art of comics. Sperandio has a unique take on comics and pedagogy, which is reflected in the variety of talks given over the weekend.

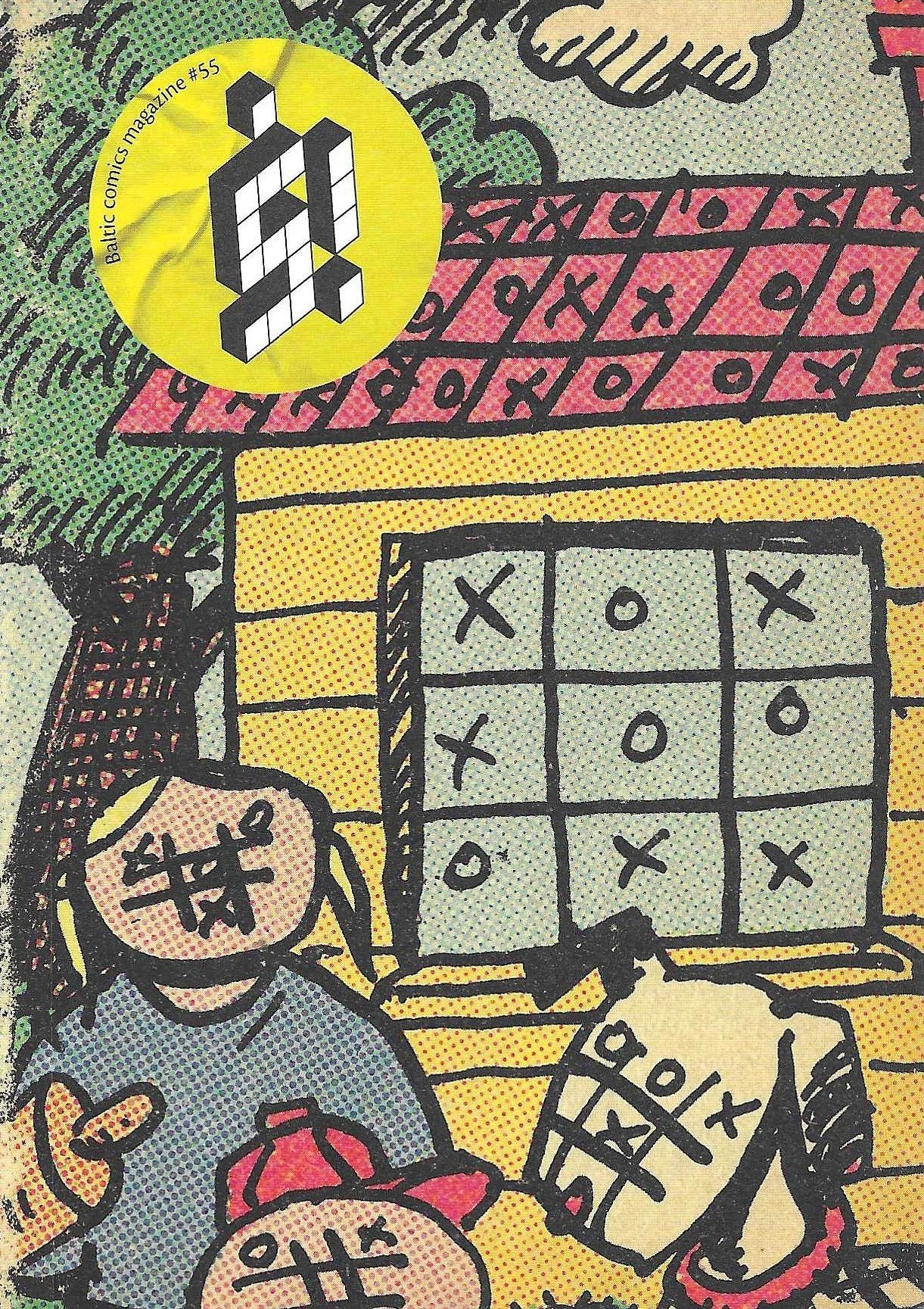

The conference was organized around panels in which guests—some academics, but also some cartoonists, publishers, and amateur scholars. Accompanying the conference was a book publication of š!, a tiny squarebound comics anthology published several times a year by Latvian alternative comics publisher kuš!. This kind of direct connection with one of the leading publishers of art comics seemed to me quite a coup, but the biggest coup was arranging to have Art Spiegelman as the keynote speaker. I was pleased to hear Spiegelman’s talk about most of his entire career as a cartoonist and editor. I was slightly disappointed that Spiegelman gave short shrift to his editorship of RAW, one of the first art comics anthologies and a direct ancestor of all art comics anthologies, including š!. I would love to have heard what his thinking was as far as RAW’s distinctive oversized format, the artists he chose to publish, his overall philosophy as an editor. But he was a very charming speaker—one gets the idea that this is a talk he’s given many times. In another coup for the conference, Sperandio arranged for the cover of the Comics Sans Frontières issue of š! to be drawn by Spiegelman.

The publisher of kuš! was here for the conference. His name is David Schilter. It may seem weird that one of the preeminent publishers of art comics in English is located in a tiny former Soviet republic. Latvia is small—the population of the country is smaller than the population of Houston, and the Latvian language has only about 2 million speakers in the world. Sperandio convinced Schilter to publish a special issue of š! just for this conference, and its contents serve as a good outline to what was discussed in the panels.

Previous numbers of š! were 100% comics (the only text in any of the copies in my personal collection is a short essay on Australian comics in a issue #37, a special Australian comics number), so the 60 pages of text in š! #55 was a challenge for Schilter. Schilter was originally from Switzerland and was inspired by the small press comics culture there—the great experimental anthology Strapazin and the Fumetto Comics Festival in Lucerne, his home town. He wanted to try something similar in Latvia. Schilter has a short essay in the Comics Sans Frontières issue of š!, and his description of the early years of kuš! will sound familiar to anyone who has worked for small press publishers (like me): making contact with distributors (one of his first distributors he contacted in America was John Porcellino, a gifted cartoonist who runs a small press distribution company called Spit and a Half). kuš! is not a profitable publisher (alternative comics publishing is a risky business—two publishers I worked for went bankrupt), and if you look up individual issues of š! on the kuš! website, it will list the artists in the issue, any honors that issue received, any reviews, and any outside support. Many issues got funding from the Latvian State Culture Capital Foundation, but the funding sources vary widely. If they are doing a special issue on Czech or Australian comics, they arrange funding from the Czech or Australian government. The Comics Sans Frontières issue was funded by various Rice University departments. Experimental art has always required patronage, regardless of the medium.

My impression that comics as a thing at Rice University (and therefore the whole Comics Sans Frontières conference) is due to the energy of Chris Sperandio. He is the one who started the Comic Art Teaching & Study Workshop at Rice, and as an art professor has encouraged students to draw comics, has exhibited original comic artwork, and encouraged Fondren Library to establish a collection of original comic artwork.

Ever since I first saw that people collect original comic book artwork (I learned that this was a thing while attending various iterations of Houston Con in my early teens), I have imagined a comics museum. There have been several attempts in the US, and the one that succeeded was The Billy Ireland Cartoon Library and Museum in Columbus on the campus of Ohio State University. But the history of comics is vast and there is room in the USA for at least one more comic art museum. How does one make this happen? Sperandio and Rice University librarians K. Sarah Ostrach, Amanda Foche, and Rebecca Russell have made a start. The most expensive part of such a museum would be the building—but even the most expensive piece of original comic art is shockingly cheap compared artworks sold in the fine art market. So it is a reasonable strategy to acquire a collection first, then worry about how to house and display it later.

Since Sperandio had already established the practice of teaching art students how to make comics, he could justify collecting original art as acquiring teaching materials for his students. He’s not building a museum exactly—the collection Rice is establishing has a pedagogical purpose. The name of the collection is the Comic Arts Teaching and Study Collection, and it is a deeply weird collection of comic art.

All of the artwork CATS has received was in the form of gifts (which is mostly true of the Billy Ireland Museum as well). The Lewis and Vera Kaminester Gift consists mostly of comic strip art from about the 1940s to the 1980s, and they recently got something like 1,800 pages of original Jack Katz art from Katz’s ex-wife. These kinds of acquisitions could form the basis for a future museum collection. It might take a while: the Billy Ireland Museum started as a collection started in 1977 by Lucy Caswell, but the museum building wasn’t opened until 2015. If Rice takes that long to build a comics museum, I’m pretty sure I won’t live to see it.

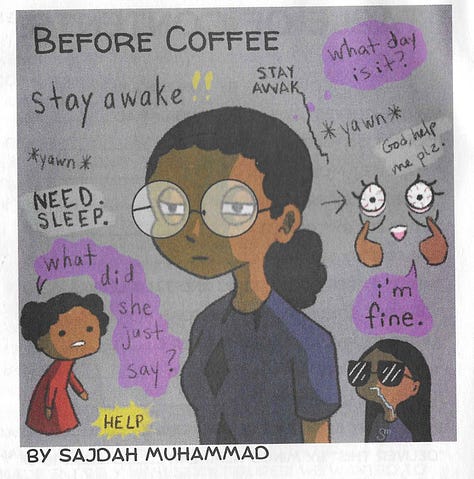

The presenters seemed to consist of every Rice faculty member who ever had any interest in comics, including David Messmer, the Director of the First-Year Writing Intensive Seminar Program. (Whoever named that program had a gift for boring bureaucratese.) This is a writing program that all Rice undergrads must complete to get a bachelors degree, and Messmer for over a decade has been teaching comics in his FWIS classes. After teaching a section called “Graphic Blackness: African American Comics and Graphic Novels”, he learned that his students weren’t just interested in reading comics—they wanted to produce them as well. He got a little money from Fondren Library and has produced two issues of Campus Comics! so far. I was quite impressed with the students comics—way better than the ones I was making when I was an undergrad at Rice. (I produced a comic strip called “Iron Shrapnel Man” in 1985 for the Thresher, Rice’s student newspaper.)

I would have killed to have something like this when I was an undergrad. Campus Comics are modest publications—issue one is formatted like a standard American comic book, while issue two is tabloid sized. Both are printed on newsprint with full color interiors. One complaint I have is that there should have been an “about the cartoonists page” in each issue. A lot of these students are talented—I would love to know more about them! The Rice student community is not huge: there are only 4700 undergrads who presumably have to take FWIS classes. That is a tiny pool from which draw enough cartooning talent to fill two comic books.

The weirdest talk I heard from a faculty member was from Jeffrey Kripal, a religion and philosophy professor who describes his interests thus:

What I am most interested in writing about is the relationship between the altered states of intellectual history, science fiction, superhero comics, literary creativity, and the deeper history of religions. I do not posit that great thinkers and artists “think” or “imagine” their way to their works. Rather, I show that their ideas and works are revealed to them in altered states and demand a kind of accounting, a type of telling that they themselves feel strongly called toward. There is a kind of fundamental passivity to such showings, but also a kind of wild activity that then ensues.

With a lead-in like this, I had no idea what to predict. My assumption based on this is that he would be deeply interested in science fiction writers like Philip K Dick who had religious visions. For his talk at Comics Sans Frontières, Kripal spoke about Jack Katz. Katz is a veteran journeyman cartoonist who worked for a series of the shittiest, most exploitative publishers of the post-war era. Katz saw visions of some sort ever since childhood. Over the course of his career, as he was able to carve a small amount of control over his own artwork (as opposed to being assigned to a title by an editor and working with a writer), he started to draw his visions as a narrative. In the mid-70s, inspired by the small-scale publishing of comics by the underground cartoonists, he started self-publishing his visionary comic, The First Kingdom. Rice University has surprisingly been the recipient of all the original art from this 768-page epic. But if you look at Katz’s art, you may be forgiven for thinking that it’s a little dumb.

My negative opinion about Jack Katz’s comic art demonstrates how removed from the academic study of comics I am. My thinking is closer to that of an art museum—I am interested in the most esthetically significant comics. But one of the artiest comic scholars of comics I know, Bart Beaty, wrote an excellent book-length study about some of the least artistically significant comics, Archie. Archie is important in lots of non-artistic ways and therefore worthy of study and analysis. Kripal by focusing on the visionary aspects of Katz has found a way into this art that I wouldn’t have.

Closer to my “art museum” view of comics was Caitlin McGurk, who gave a paper on mostly forgotten New Yorker cartoonist Barbara Shermund. Shermund was born in 1899 in San Francisco into an artistic family, and by 1925, she had moved to New York and started contributing to the nascent New Yorker magazine. She was a very frequent contributor of cartoons, illustrations, and covers, and drew in an elegant style well-suited to the flappers she loved to depict. McGurk recently published a biography of Shermund, Tell Me a Story Where the Bad Girl Wins.

When I heard McGurk give her paper, I could see that her rediscovery of Shermund was similar to something that sometimes happens in the art world. If you are an art critic, what can possibly be more gratifying than to relaunch the career of some long-forgotten artist? There are art critics who pour through old issue of Artnews, looking for someone who got reviewed once or twice before dropping off the critical radar; they start digging and with any luck, they’ve added a new name to the canon of greats. A big part of this strategy involves looking at artists who for some reason were not given a chance—they were outsiders in some way. For instance, if they were from a place far from a cultural capital like New York or Paris, or if they were were black, or they were women. Like Barbara Shermund.

I said that McGurk’s academic interest is more “art museum” than purely academic, which makes sense since she is Curator of Comics and Cartoon Art at the Billy Ireland Cartoon Library and Museum. Alumnus Milton Caniff donated some original comic strip artwork to OSU, which was the beginning of the collection. From this relatively humble beginning came a large physical museum across a plaza from the Wexner Center for the Arts. Perhaps Rice will have one of these one day.

Beyond academic presenters, several of the presenters were cartoonists and one was a fanzine editor. Brian Baynes is the editor of a supurb comics fanzine called Bubbles. Hearing him speak about the work that he and his collaborators are doing reminds me of being a young editor for The Comics Journal in the early 90s. The fact that there are still young critical minds producing incredible critical publications completely outside the mainstream or academic world 30 years after my own experience in that world is thrilling to observe but also a reminder of how far comics still has to go. Back in the early 1980s, the editors of The Comics Journal concluded, “We know what good comics are—lets publish our own!” Bubbles has repeated that story—after several years of producing the fanzine Bubbles, Baynes has recently published several important early manga in English for the first time, as well as a contemporary comic from India.

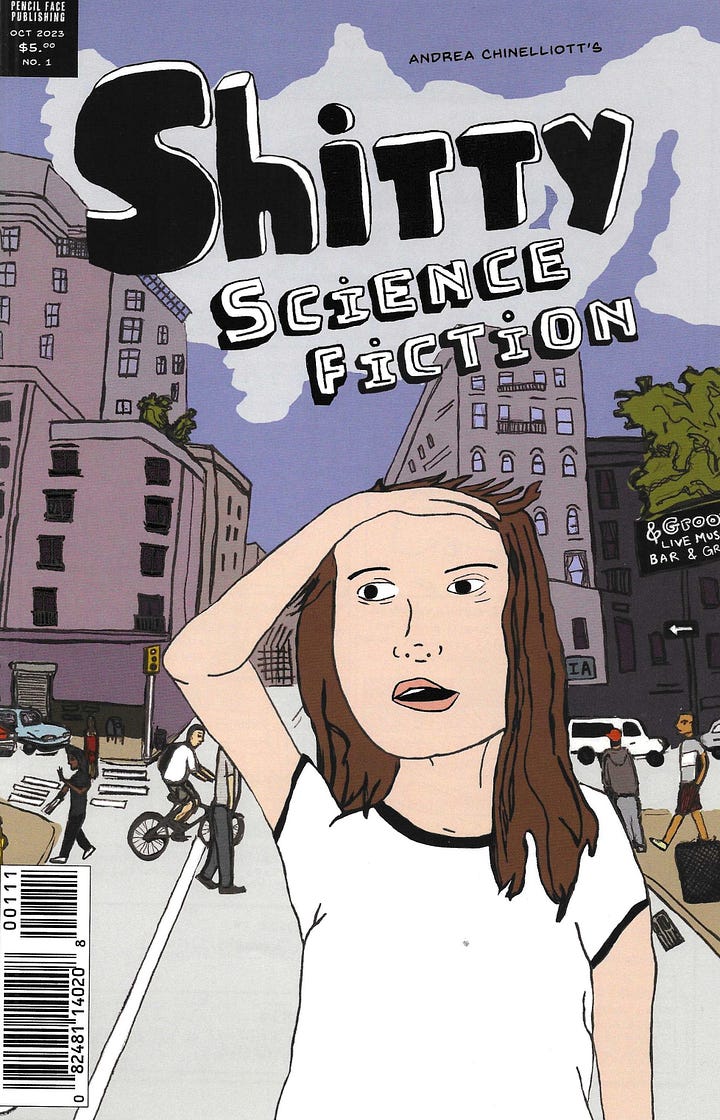

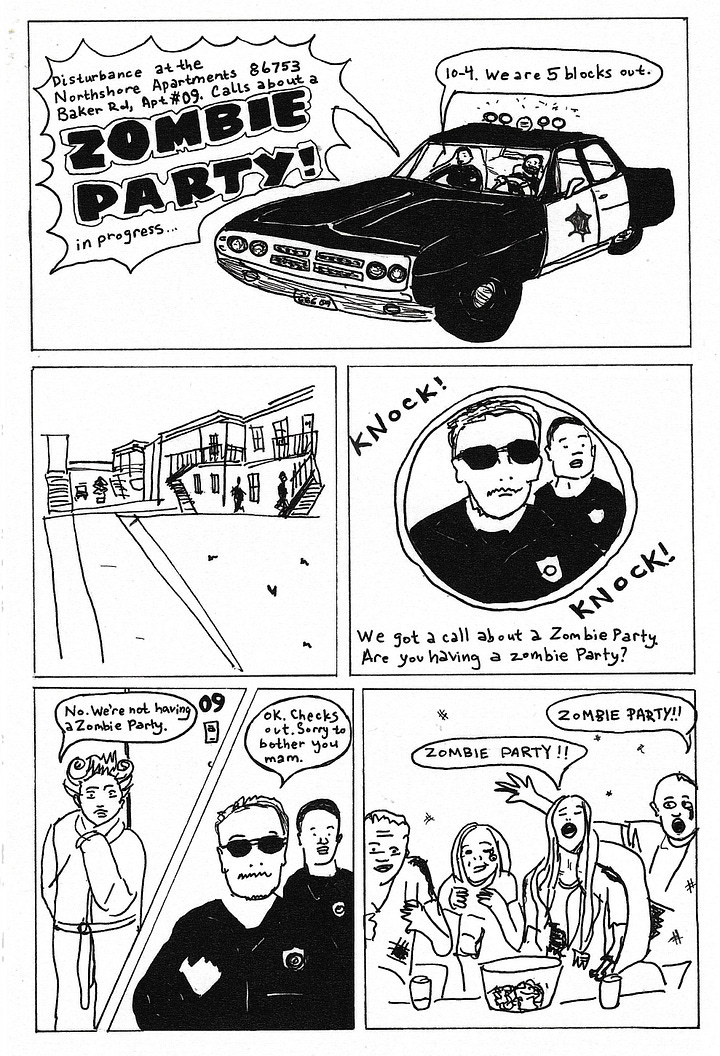

Part of what I got from the conference was the presentations themselves, but I also met some young Houston cartoonists who attended. Two that I will keep my eye on are Andrea Chinelliot and Nico Rodriguez. Chinelliot gave me a copy of her comic Shitty Science Fiction. She and her husband form a two-person comics collective called Pencil Face Publishing. Nico Rodriguez has published several comics over the vears—the latest post on his substack, Wicked Green Monkey Press, is an unboxing celebration of his latest comic, Eclosion: An Alien Love Story.

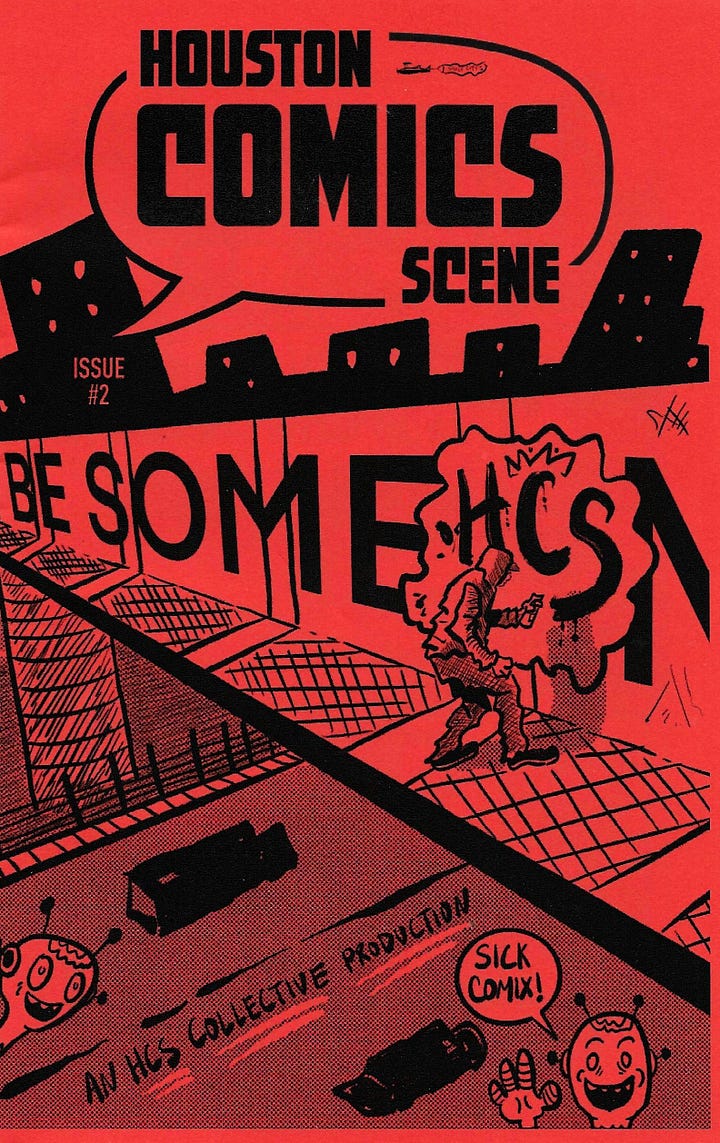

In addition to meeting these two young cartoonists, a zine by the HCS Collective, which included comics by six Houston cartoonists (including Nico Rodriguez), was given away at the conference. The name of the zine is blunt: Houston Comics Scene. There appear to have been multiple issues published in the past. I know that some have been given away for free at Texas Art Supply, but I don’t know if you can find any there now. The point I’m making is that here in Houston there is a thriving indie comics subculture about which I knew nothing. And I’m sure the same is true in any sufficiently large metro area. When I worked in the comics industry in the 90s, I felt I could identify every important art cartoonist in the country by name—now I can’t even name all the most important cartoonists in Houston. Part of that is due to the fact that I’ve somewhat withdrawn from the subculture for the past decade or so, but it mostly speaks to the vast increase in production of comics.

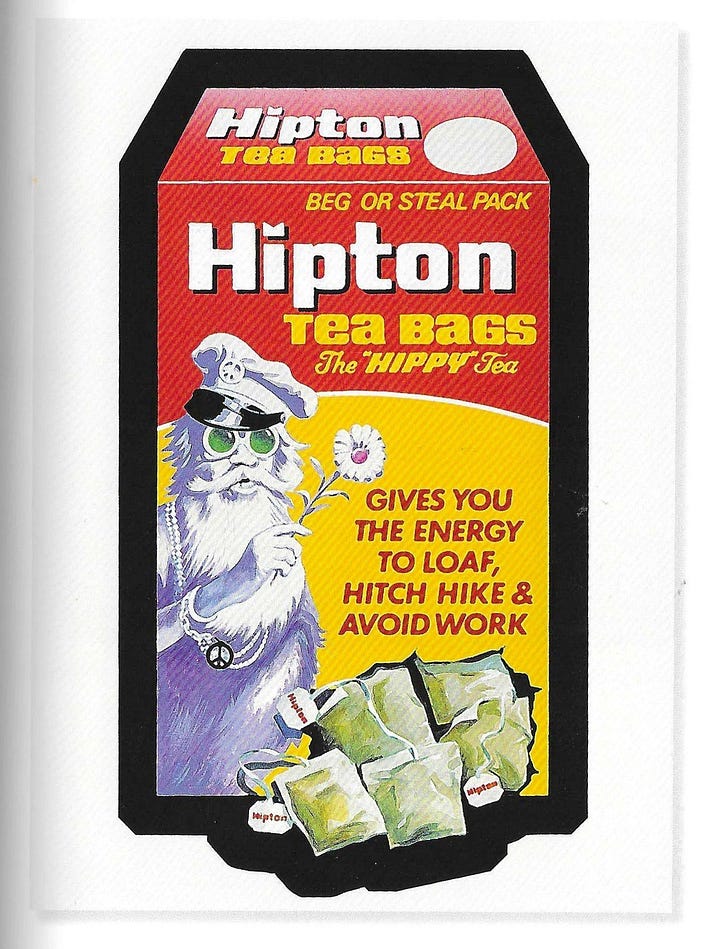

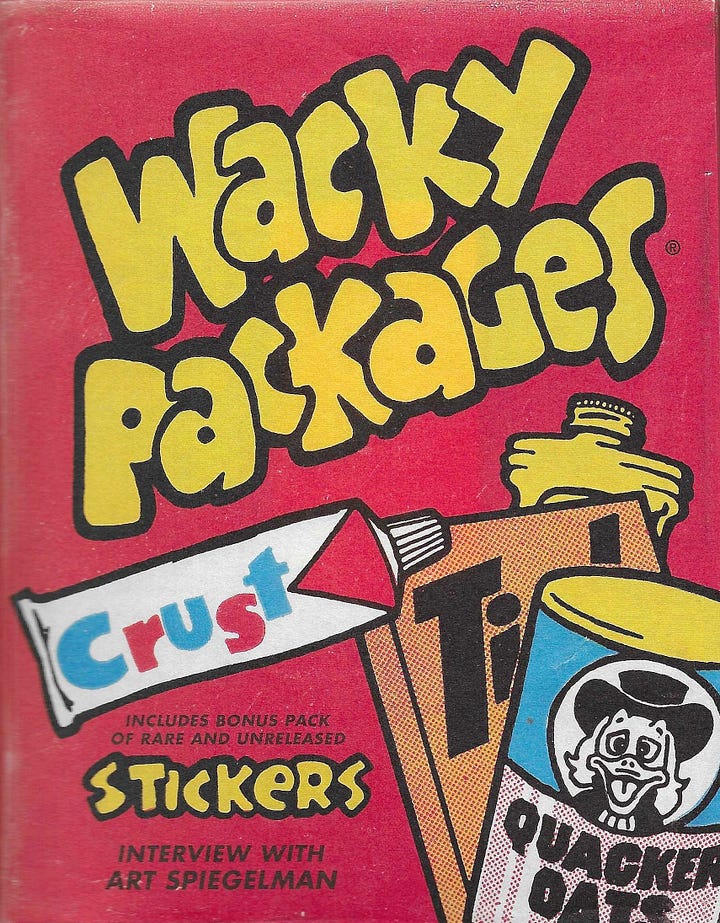

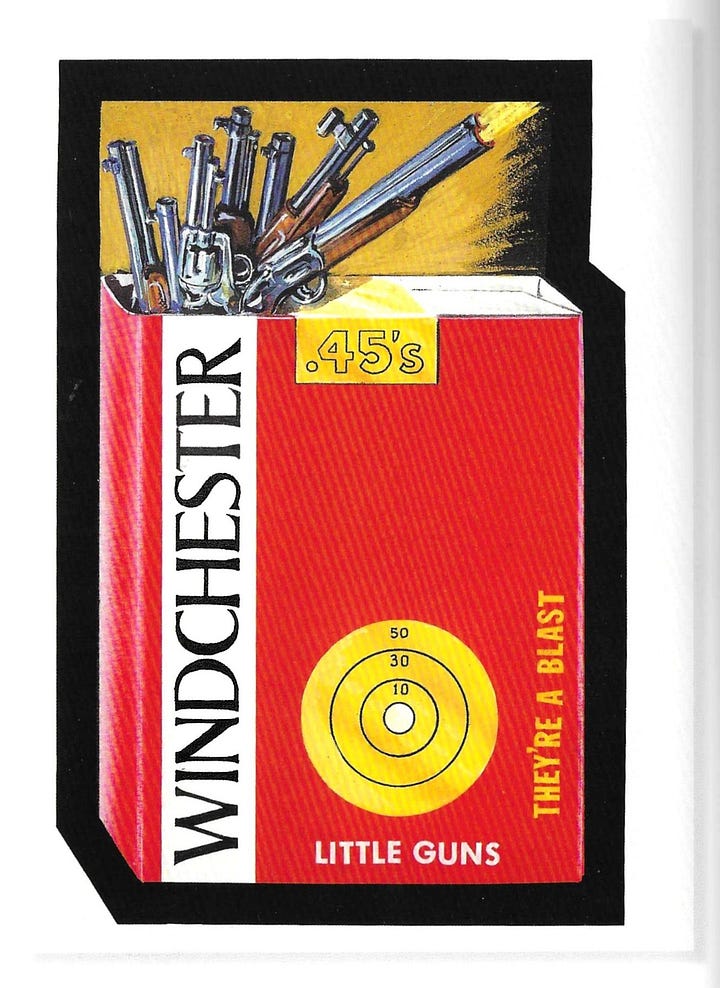

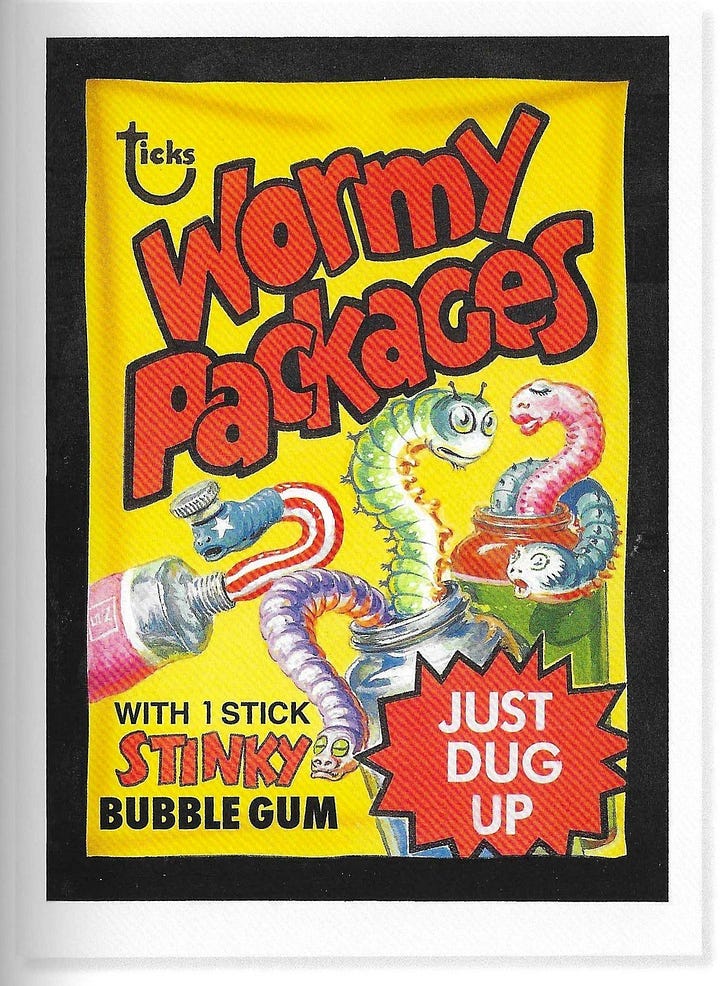

The dominant culture doesn’t really notice tiny subcultures like the Houston comics scene, but in the past few decades, it has become impossible for major cultural institutions to completely ignore the art of comics. This was brought home by the presence at the conference of Charles Kochman, the editor of Abrams Comic Art. Abrams was founded as an art book publisher in 1949. The first fancy art book I ever got for Christmas was an Abrams book about Diego Velázquez. The fact that Abrams has embraced comics tells me that the barriers between high cultural institutions and comics are thinning. Kochman brought goodies, including copies of Wacky Packages, a book collecting several years worth of bubblegum stickers produced by Topps, the big baseball card company. These were produced in the early 70s and shipped out to convenience stores and newsstands all over the USA, where little Robert Boyd gleefully bought them. When I think about it now, Wacky Packages were the first pieces of culture—of art—that I ever spent my own money on. They were parodies of commercial product packaging, and their link to comics is that many of them were written by Art Spiegelman. I had a mirror in my bedroom that eventually got covered with these stickers. Spiegelman spoke proudly of his role in creating these things in his talk, because they, like the MAD comics that so influenced him as a child, made fun of the adult, corporate world. They were slightly subversive.

[Please consider supporting this publication by becoming a patron, and you can also support it by patronizing our online store. And one more way to support this work is to buy books through The Great God Pan is Dead’s bookstore. ]

What a great conference! I had no idea that Rice had this much comics-related activity! I loved all of the panels, and it was small enough that I was able to meet and talk to a lot of the participants. And I made some new Houston friends (the cartoonist you mention in your article and their friends). And it was nice seeing you as always. I hope there is another one next year!

Thank you for reporting on this. I had plans to go Friday but life got in the way. I’m glad I got to read about it at least.